ARTWRITE #22: Working With Memory

feat. B. Chehayeb, Bea Denton, Heather Evans Smith, Brandi Twilley

August 14, 2020

I started thinking about a memory issue months ago when I planned to include Brandi Twilley in ArtWrite #17: Inside Sketchbooks. Once I learned how Twilley accessed, captured, and considered memories, I wanted to talk to other artists who worked with memory. I was especially interested in how they dealt with memory's fallibility because memoir and personal essay writers face this challenge all the time.

Student writers inevitably express anxiety about their ability to recall the past. They want to explore prior experiences but worry about remembering what someone said or where an incident occurred. These concerns are counterproductive. In The Seven Sins of Memory, Harvard psychologist Daniel Schacter explains why memory can't be trusted by categorizing the ways it can malfunction: transience, absent-mindedness, blocking, misattribution, suggestibility, bias, and persistence. Once writers accept that it's just not possible to pin down their memories, they can move forward.

I grew up in the shadow of an older sister who ice skated competitively. Every time we'd go to the rink, our textbook skating mother would watch my sister practice and ignore me. So when I wanted to capture these memories, I wrote a scene set at a rink. You can read it here.

The fact that this scene never actually happened isn't important. What matters is that I stayed true to my memories of the characters and the situation. From there, I combined sense memories, made-up dialogue, and some research on axels.

Some might say my approach is dishonest, but not multiple-memoirist Dani Shapiro: "To think that memoir can be fact-checked is to misunderstand the whole idea of what memoir is. Which is to say, a story. A story told by a writer who is plumbing the depths of her memory. Who understands the sacred pact she is making with the reader. This story is what I remember. This is the truth of my memory–which is faulty, singular, mine alone. It is not The Truth."

The most important part of working with memories is making sense of them. It's not enough for the writer to capture her memories as she relives them. The writer then has to determine what she wants to say with the material, make meaning of it, and shape the material accordingly. (That's why my skating scene remains stuck in a folder labeled "memoir" on my laptop).

The painters and photographers you'll meet in this issue each tackle some version of this daunting step in the creative process. To paraphrase the writer, Vivian Gornick, what happened to the writer doesn't matter; what matters is how the writer makes sense of what happened. The same is true for artists.

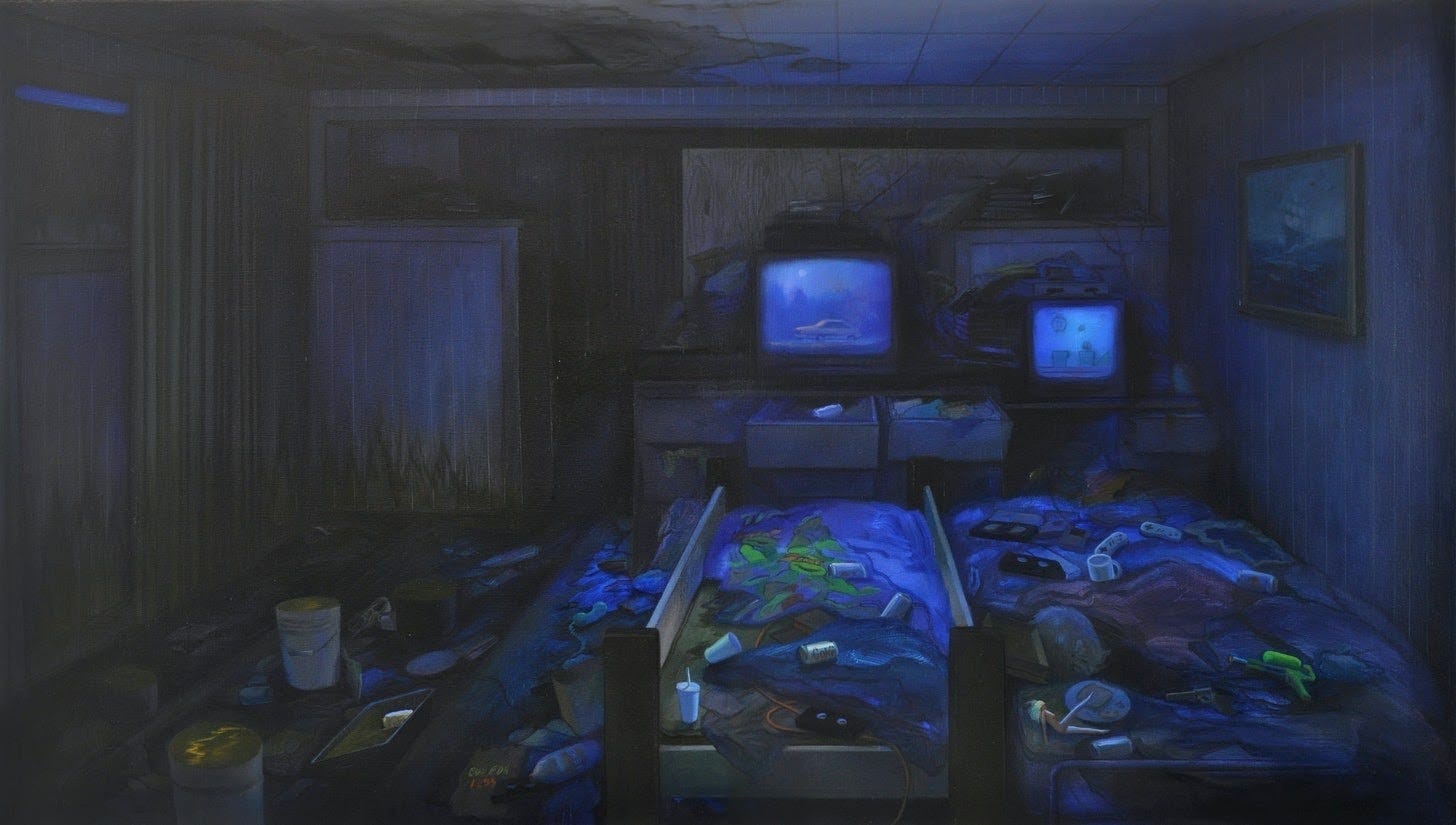

Brandi Twilley

Brandi Twilley was 16 when a fire burned down her childhood home. In the years that followed, she often had dreams about her home and sensed it would become a subject in her work.

Fifteen years after the fire, Twilley began drawing her home from memory. This practice allowed her to reclaim a part of her life for which she owned almost no record. Only a few photos existed, and she didn't remember it well. "I was trying to create things from nothing, from memories that I'd lost."

The process was slow. Over four years, Twilley made at least a hundred drawings. The practice allowed her to free associate; the more she drew, the more details emerged.

The paintings that emerged from these drawings have a hazy feeling that reflects the way memories, especially traumatic ones, become blurred in our minds. Some of the objects appear vague and unrecognizable, suggesting the limits of Twilley's memories.

Twilley's memories didn't just infuse the content of these paintings. They also affected formal aspects such as the shifting scale and shape of objects and her use of light and dark. Since her memories of the light in the room were clear, Twilley rendered it with specificity on the edge of a bed rail or filtering through the top of a boarded window..

In a 2017 interview with Romanov Grave, Twilley describes how her paintings gradually moved from a normal value range into a darker one. "Even if I tried to fight it, I would be immersed in the details on the wrapper of a candy bar and then step back from my painting and realize it had turned so dark that I could barely see what I had been working on."

Initially disconcerted, Twilley wondered if there was a problem with her studio's lighting. But, eventually, she stopped resisting. "The difficulty in seeing [the paintings] mirrors the difficulty of making them, the slowness of remembering what the space looked and felt like, and what was in it."

The murky darkness also works because its mixes of magenta, viridian, and umber evoke the colors of analog photography, the same era that the paintings depict. The visual reference gives the constructed memory "a bit of photographic plausibility" that Twilley likes.

Twilley ended up making a ten painting series. The Living Room encompasses multiple years, from the slow decline of the house before the fire to when it eventually burned down. The images in the series look nothing like paintings made from life and are far from photo-realistic. Instead, they are "archaeological reconstructions," amalgams pieced together from 90's-era images she found on Google, her few surviving photos, and details that appeared in her dreams.

When asked about the role of dreams and memory in her practice, Twilley noted their similarity. It doesn't matter that it's impossible to make concrete forms from either. The goal is to capture their emotional content.

Heather Evans Smith

When Heather Evans Smith was a child growing up in Kinston, North Carolina, she loved to visit her grandmother at the department store where she worked as a seamstress. The alterations department was a playground where Smith would lose herself in the whir of machines, hide in the dressing rooms, and plunge her arms into boxes full of buttons.

As an adult, Smith can remember the love she felt for and received from her favorite grandparent but had never known who she was as a person. "I just knew she was nice to me. This is kind of how we are as kids. Was that person nice to you or mean to you? I don't know all the specifics that I would have learned had she been around as I got older."

In 2017, Smith began a project about how sewing used to be an essential skill. But over time, her focus shifted to her memories of visiting her grandmother at work. (In many of the photos, Smith's daughter serves as a stand-in for when she was a child). Smith even taught herself to sew for the project. The resulting series, "Alterations," includes 21 images that serve as "metaphors for the way we alter, mend, and piece together memories, to make sense of what we have lost."

Smith sourced vintage clothes and sewing-related paraphernalia to evoke 1970's colors and styles but didn’t get hung up on accurately recreating every detail of her memories. For example, she remembered that the dressing rooms in the alterations department had "this two-step carpeted little stage and mirrors" but didn't feel compelled to include them.

Staging and shooting from home presented limitations, but as many artists know, restrictions often pay off. "I thought legs peeking out underneath would be interesting and found some shoes and knee-high socks to contrast against the color of the curtain. So there was a lot of play with that memory. If it were really realistic to the time, it would probably be some dirty beige carpet and me hanging off a door. It's a matter of what I think makes a strong image."

Smith's images also succeed in conveying the emotions woven into her memories. The menacing vibe of Pins and Needles alludes to her childlike fear of seeing how the ladies in the alteration department kept pins in their mouths. "It was an easy way for them to hold them and pull them out while they're pinning something. But what if they swallowed one? There was that danger."

Images like Class System evoke the closeness she felt towards her grandmother. Ladies would bring Izod shirts to the alternation department to remove the logos, and Smith's grandmother saved the alligators in a box. She'd then sew them on Smith's own K-mart shirts to make them appear more expensive.

Smith was six when her grandmother made the dress in the photo Deconstruction Of A Memory. By pinning a threaded needle to one sleeve and flipping the garment inside out, Smith brings the dress back in time, reverting it to a work-in-progress while rendering the invisible visible. We see how Smith's grandmother constructed the dress and can imagine her piecing it together. The exposed seams remind me of a secret language waiting to be unlocked by those who know how to read it.

Bea Denton

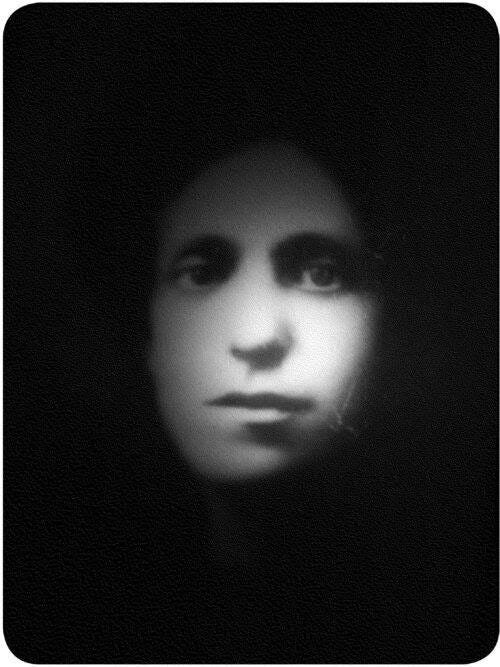

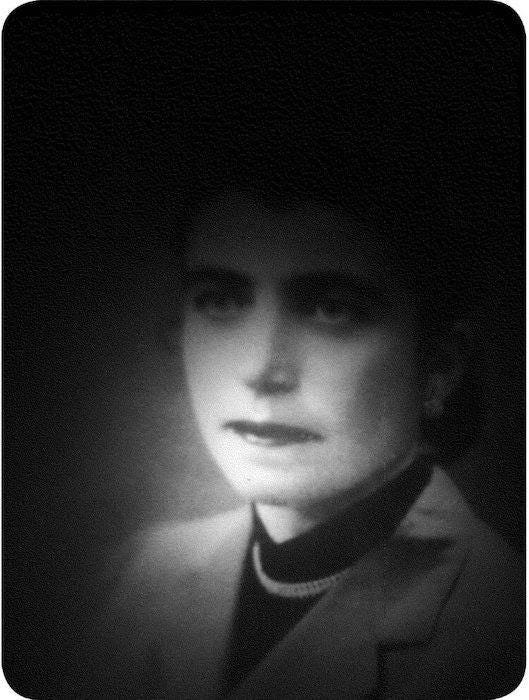

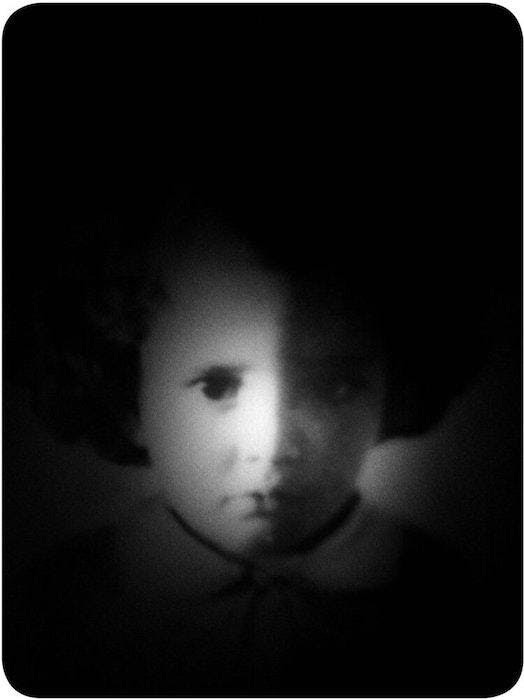

In On Photography, Susan Sontag asserts, "photographs are a way of imprisoning reality ... One can't possess reality, one can possess images--one can't possess the present but one can possess the past."

But what happens if you don't have any images of your past?

Bea Denton can answer that question. Her parents never owned a camera. No images of her as a child exist, and she has no recollections of her life before about ten. Interestingly, or perhaps consequently, Denton has always gravitated to photographs because "they have that ability to provide indisputable evidence about happenings or people existing. Without them, you start to question those things."

Losing a young sister to an aggressive form of cancer fueled Denton's preoccupation with the ephemeral nature of existence. Questions about death tormented her: Where do dead people go? Is there a soul? Cemeteries had always fascinated her, and on visits to them in Italy, Portugal, and Greece, Denton found consolation in an unusual genre of photography, tombstone photos.

Taking photos to place on gravestones in the future became fashionable at the end of the 19th century when two French photographers patented a process to adhere photos to porcelain or enamel. Ceramic pictures made gravestone photos affordable and became popular throughout Eastern and Southern Europe and Latin America.

Gravestone photos reflect our innate desire to remember and to be remembered. Taken with the end in mind, often when the person was young and healthy, they acknowledged the end of life, a memento mori made in advance of death. (Photos of babies and children were not likely taken with this purpose in mind).

The tombstone portraits became a catalyst for Denton to examine the nature of perception and memory. That's when her practice shifted from taking photographs to "borrowing" images of the deceased.

In the cemetery, Denton's camera is a tool for revelation, while in the studio, she "penetrates and excavates the essence of the image to the very core of its being." First, she projects the tombstone portrait on the wall; then, she re-shoots it through the lens of a camera obscura. That image is then re-created as an etching and printed on a press.

Denton doesn't know which portraits will be successful until she subjects them to her process. There's usually something elusive or enigmatic about the image that makes her want to capture and examine it; the eyes are often the focal point and seem to challenge the viewer with a question.

Denton's prints are meant to be tactile objects and are float-mounted in deep box frames. Collectors often confer their own associations on her images. They, too, understand that an image doesn't convey a truth or a narrative. "It's a mnemonic, if you like, a vehicle for remembrance. Not a representation but a reinterpretation that triggers associations and memories for others."

Songs of Lamentation, an evolving body of work, includes souls Denton has "captured" from tombstones across Europe since 2014. Her archive includes images from more than 1000 tombstones.

Denton's practice is labor-intensive, but she welcomes the meditative quality of work. It helps her with the universal dread we all feel, and Denton experienced when she lost her sister. "I feel like she's not alone, and we're not alone; there is this universal universality about the whole process of existence."

B. Chehayeb

Memories became the focus of B. Chehayeb's artwork when she moved from Texas to Boston to attend graduate school in 2018. To cope with loneliness and cultural isolation, the artist began to examine her Mexican-American heritage and culture and the future of her identity. "I wanted to illustrate the disconnect between my several identities as I grew older and increasingly found myself isolated from everything familiar. I wanted to remember me before."

For Chehayeb, memory was a bridge between past and present and visual arts and writing. She paired object-based assemblages with stories and writing to create a dialogue about nostalgia's power. As Chehayeb worked to capture memories that exist at various levels of accuracy, she discovered that language wasn't up to the task and embraced the idea of being a "failed poet." Over time, her work morphed into abstractions that use erasure and fractured images to capture impressions of fleeting moments.

Chehayeb's work is a means of preserving memories. She is determined "to understand the psychological monuments one cannot or refuses to leave, to avoid the catastrophe of forgetting."

ross says he misses god from the edge of the bed refers to a conversation between Chehayeb and her partner. After leaving behind the language and traditions of the Bible Belt, the couple could feel how the move was tearing apart their spirituality and identity. The painting's visual references to dying plants, bodies outgrowing clothing, and teeth convey how in this moment, the "inevitable wind of change" frightened Chehayeb.

The images in Chehayeb's work stem from a range of memories, including her transitory childhood, Mexican-American culture, broken relationships, divorces, financial struggle, and trauma relating to religion, sexuality, and gender. Each work connects to an object, place, or theme, and their titles specify the event or instance depicted.

buying coats alludes to the artist's memories of her grandfather taking her and her siblings to buy coats when her mother couldn't afford them. "This was usually right when there was a chill of winter wind picking up in the south, cold and warm with the sun. Walking into Burlington coat factory from the parking lot, top layer of skin warming back up as we walked in the building. Not quite snow, sometimes Texas sleet or just a wind that bites."

You can't force memories to surface, and Chehayeb has learned to keep tabs as they can emerge at any time. That means "writing them down as they come, lots of iPhone notes and voice memos, solitude and reflection."

She uses a process she calls "mapping" to trace memories to their origin as far as location, colors, smells, etc. She also identifies the parts of a memory that may be mistaken, fallible, created by accident, or came from someone else.

Chehayeb is interested in how "emotions, nostalgia, and trauma thwart and confuse the truth behind a memory." A fan of Joan Didion's" 'On Keeping a Notebook," she believes that what we remember is just as, if not more, valuable as what was. "It's the final iteration in the mind that matters most because that holds the emotion and the spirit."

Of course, I couldn't agree more.

I just went back to this to read again. It’s also one of my favorite Artwrite issues … the crossroads between memory, art, writing … few subjects are more interesting to me than these. Thank you, Maggie!

one of my very favorite issue! you’re examining everything that i care about and try to achieve in my writing. i wish i could see all these artists work in person.