ARTWRITE #17: Inside Sketchbooks

Gigi Boetto, Barbara Bryn Klare, Thor Rinden

2/13/21

Sketchbook is a misnomer. A lot more happens in these books than just sketching. Anything you can do on paper, you can do in a sketchbook: diagrams, doodling, scratching, drawing, painting, affixing items with glue, staples, or thread, or even weaving materials into the pages. Not to mention writing: poetry, reflection, recollections, musings, to-do lists. There are no rules that say "only art!"

I get why sketchbooks are so appealing to artists. It's not just that they're portable, accessible, and affordable. Thanks to bookbinding, what would otherwise be loose papers in a digital or manila file becomes a rich, tactile object begging to be opened. All those filled pages are satisfying reminders of completed work while the empty ones promise unimagined discoveries. The covers act as a frame, reinforcing whatever period the volume covers -- be it a week, a year, a season, or a trip. When the book is complete, it becomes part of a series, one more portal to the past.

Sketchbooks are also personal, a private thing. Artists don't expect them to end up on display in a museum. They're a pressure-free zone for exploration, problem-solving, and play, one of many stops en route to a final product. I like to think of them as tangible embodiments of the creative process.

This issue explores three different takes on the sketchbook practice. Gigi Boetto draws or paints, while Barbara Bryn Klare pushes the boundaries of sketching by working with thread and textiles. In his hybrid notebooks (part sketchbook, part scrapbook, part diary), the late Thor Rinden moves seamlessly between writing and drawing.

If sketchbooks interest you, definitely take a look at The Sketchbook Project. Their library includes over 25,000 sketchbooks and continues to grow. The project also has an easy system for artists to contribute to their collection.

—Maggie Levine

GIGI BOETTO

Gigi is an NYC-based abstract painter. She currently works without brushes, using her hands to rub, scrape, erase, scratch the surface of her work. After exploring different mediums over the years, Gigi has dedicated her studio practice exclusively to painting since 2013. Her work is available through SHIM Art Network.

I didn't use a sketchbook for a few years because it didn't seem necessary to my paintings, but I realized that this isn't the point. The point is to be surprised with what comes up when I'm not thinking about painting, to surprise myself with new ideas, even if they never directly influence my work. Surely sketching influences my paintings, but it manifests more intuitively or unconsciously, and I'm unaware of it until I reflect on a finished sketch. .

I don't really think much before I sketch. I grab a pencil, marker, pen, paint and then begin to move around a page, and from there, I start to see something. It could be an image, composition, or a color relationship, and then I keep going until something is created. Sometimes the sketch has several layers because I don't particularly like where I'm headed, so I take another approach.

I learn something when I'm finished. Sketches like the ones below showed me how much I like lines and the emotional clarity they create. Recently, I'm incorporating them more into my paintings using pencil. Sometimes I start a painting with lots of pencil which eventually gets covered by paint.

Sketching also helps me learn to stop. It's always a challenge to know when I'm finished with a painting. In the past, I've overworked them. Sketching helps me make those decisions without the pressure of a large canvas or panel in front of me. A sketch like the one below is an example where I said," it's done," only using two colors, and it was finished quite quickly.

Sketching also brought me back to working on paper, which I hadn't done since the beginning of the pandemic. For me, there's an immediacy to painting on paper, which is really enjoyable. And it feels less intimidating than canvas or panel because I can just rip it up if it's not working.

When I began painting, it was an outlet for my memory loss. I was processing what that meant and doing a ton of reading and research. Over time, I realized that most people have terrible memories. For instance, every time we think back to a memory, we change it slightly. And that brought me to a place of celebrating life's liminality. Now, I'm interested in the transitional and fuzzy spaces.

Sketching is a way to capture a moment, creating a memory. It's a recording that usually lacks the emotional pull that my paintings require because they are so emotionally heightened.

I usually sketch in the evenings, often when I'm tired and not in my studio. Sometimes I watch a movie. I'm relaxed and not focused on much other than what's in front of me. Sketching is freeing. Freehand. Freethinking. It's releasing and meditative.

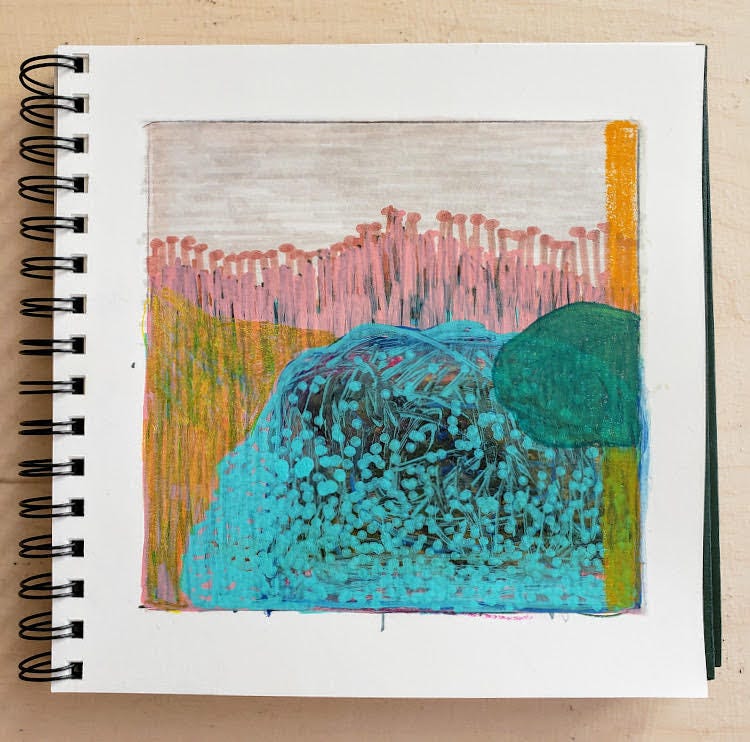

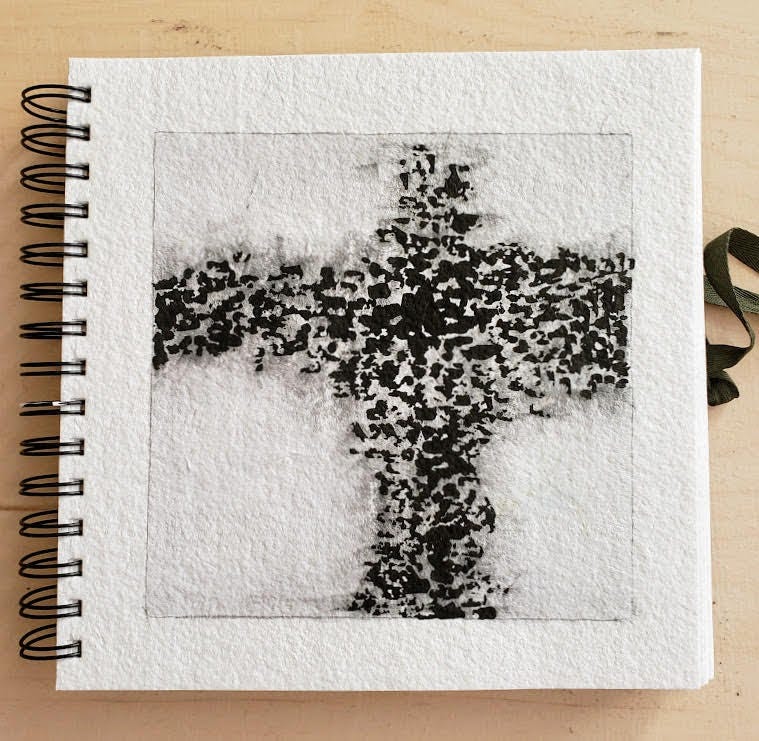

BARBARA BRYN KLARE

Based in the San Francisco area and southeastern Ohio, Barbara Bryn Klare is an artist, curator, and educator who has exhibited internationally and received numerous awards and grants. Using rescued textiles, objects, drawings, text, and natural and digital materials, Barbara's work explores fragility, repair, sustainability, and powerlessness. She discusses her practice in an NPR affiliate interview. Barbara is also the creator of WHERE Were You Harassed?, a combined public service and art project discussed in this Huffington Post article.

My art practice is deeply involved in the making of what I call “Textile Sketchbooks.” This term is not entirely my own; the textile design profession has a version related to their industry. To me, a textile sketchbook incorporates or references fiber, thread, or cloth in some way. It is “textilian” (again, my term) in nature.

The books consist of traditional, store-bought sketchbooks in which I have drawn, painted and/or glued textiles or thread, folios or collections of loose pages that I may or may not bind together in the future, and vintage books I have altered in some way.

Rescued textiles have long been part of my exploration of themes of repair, reuse, and fragility. Cloth and thread as metaphor is a recurring motif. It felt natural, then, for me to bring bits of textiles into my sketches.

We spend so much time online these days. What has happened to our sense of touch?

I have very few rules except for one particular sketchbook, which I made by painting over pages of a Japanese design book. In that book, the rule is that both sides of the spread (recto, verso pages) has to “speak” to the other in some way: stylistically, formally, emotionally, or other way.

Originally, I thought of textile sketches as preliminary sketches to bigger, more finished ideas, but my thinking has evolved into seeing the pages as art pieces in their own right. I am currently using vintage book pages as my canvas-- these books are free from my local thrift store, and because of the pandemic, they are much easier to obtain than expensive art materials.

At times, the sketchbooks have been containers for ideas: 2D spaces that hold and preserve textile-related thoughts and creativity.

Since COVID, the sketchbooks have served as a place to express what I call the achingly beautiful: the fragile self that needs protection when the outside world is so harsh and unsafe. In one series, I worked through feelings of missing the ocean and the Bay Area in a series called "Water" and another entitled "Sailing.”

I did another series on the pages from an Italian poetry anthology. My mother was a poet. We lived in Italy for a short time when I was a child; this series has great emotional importance for me.

Calling up memories is definitely a part of what I do when working with textile sketches. Since I am often re-using parts and pieces from previous work, I am also incorporating memory, past and legacy.

My textile sketchbooks have a diary-like quality in that I see not only how my ideas evolve over time but how I'm evolving. They speak directly to the power of creativity without pressure or limitations, to re-use of materials (especially by using recycled textiles and textile waste), and to an expanding definition of the word "sketch.”

THOR RINDEN

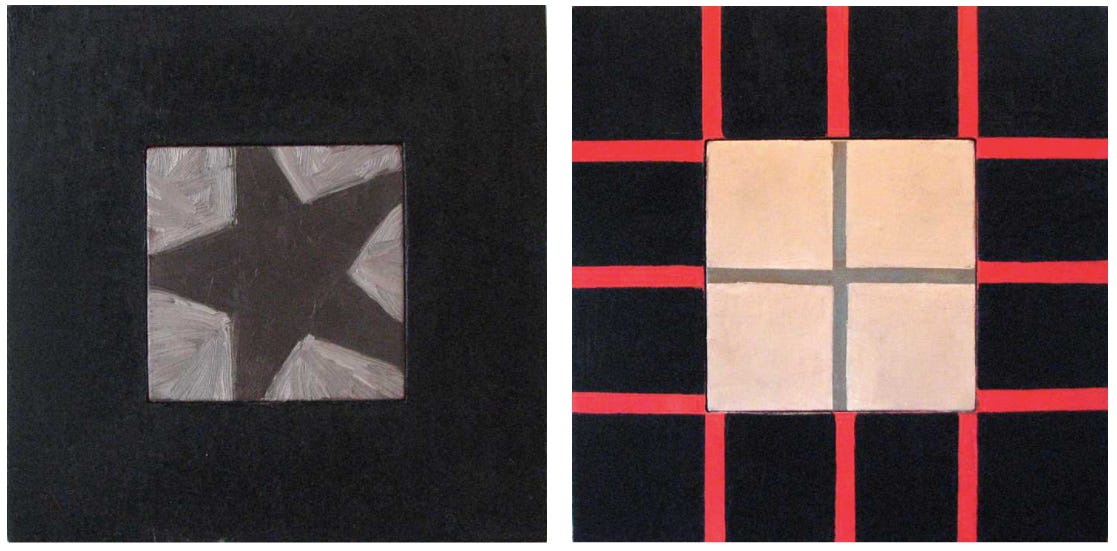

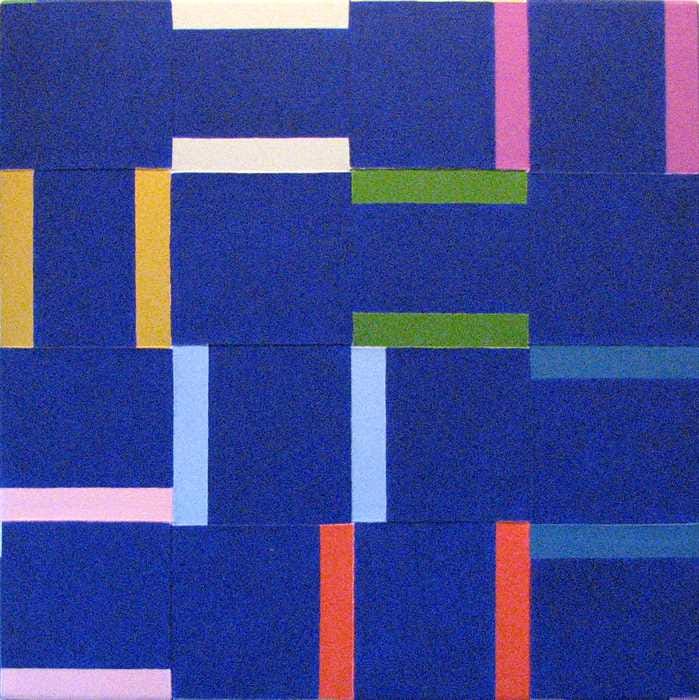

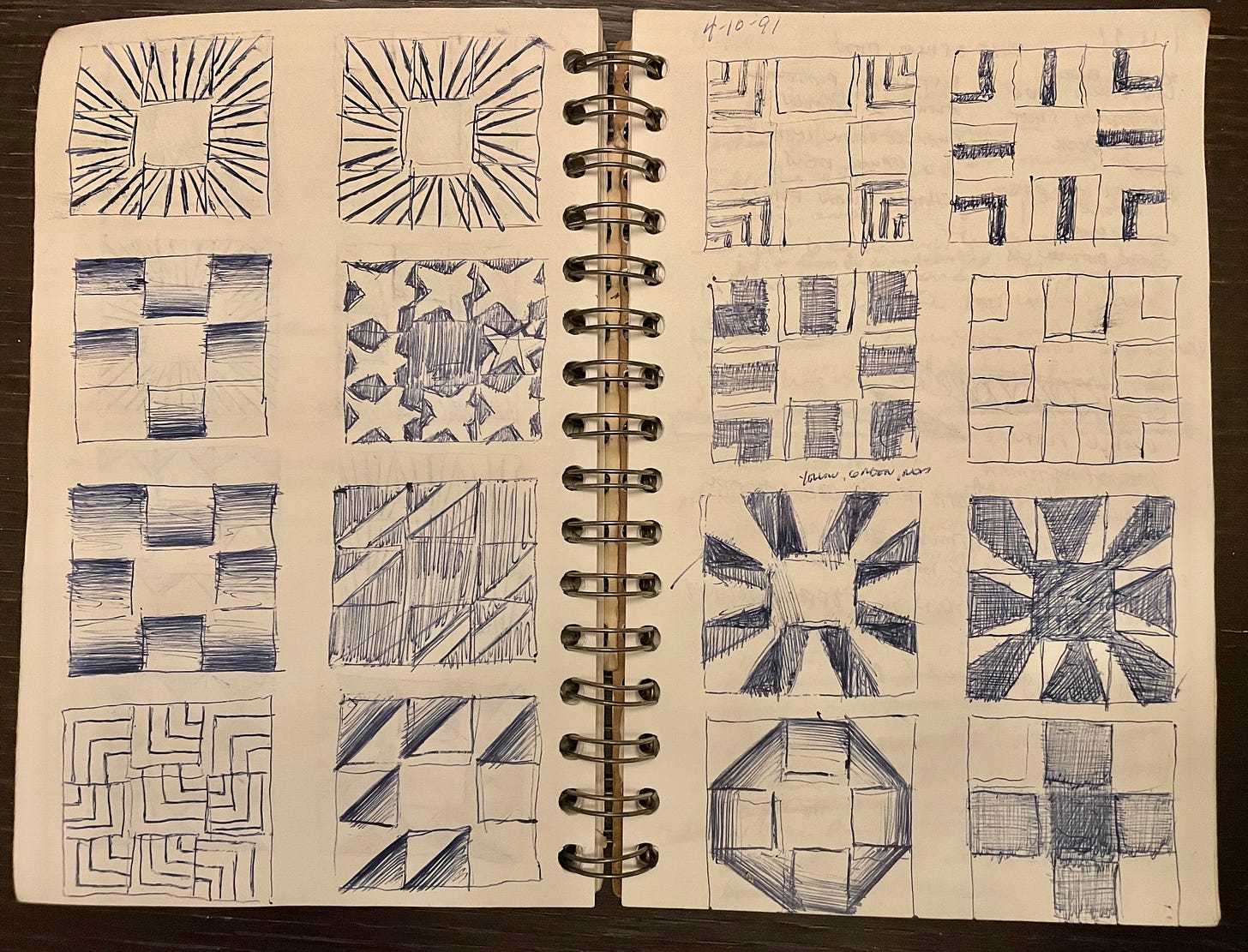

Thor Rinden (1937-2009) worked for four decades in the privacy of his Brooklyn, NY studio, producing luminous and profound paintings on canvas, wood and paper. Many of Rinden’s most original works are “wovens,” that is, works in which the artist wove colorful, interlocking strips of canvas into patterned designs, anchoring them to stretcher frames; and “slab paintings,” in which smaller, meticulously constructed canvas frames are embedded into larger ones. His work is in museums and private collections.

Rinden’s 23 notebooks span 1974 to 2006 and vividly track the evolution of his work. Dozens of puzzle-like grids and drawings reveal the artist continually playing with possibilities for his paintings, prints, and works on paper.

In an entry from 1976, Rinden considers a new approach to constructing his canvases:

“Looking at a reproduction of Matisse's ‘Egyptian Curtain’ and other works of his where he combined numerous patterns into one composition, it struck me that my own motifs might well be put together in a structural - constructive way that would allow plenty of visual and color interest. Also if sections were made and painted separately, then combined into a square composition, the surprise of something unplanned as in collage would result. And the square format would tie the individual sections into a single composition.”

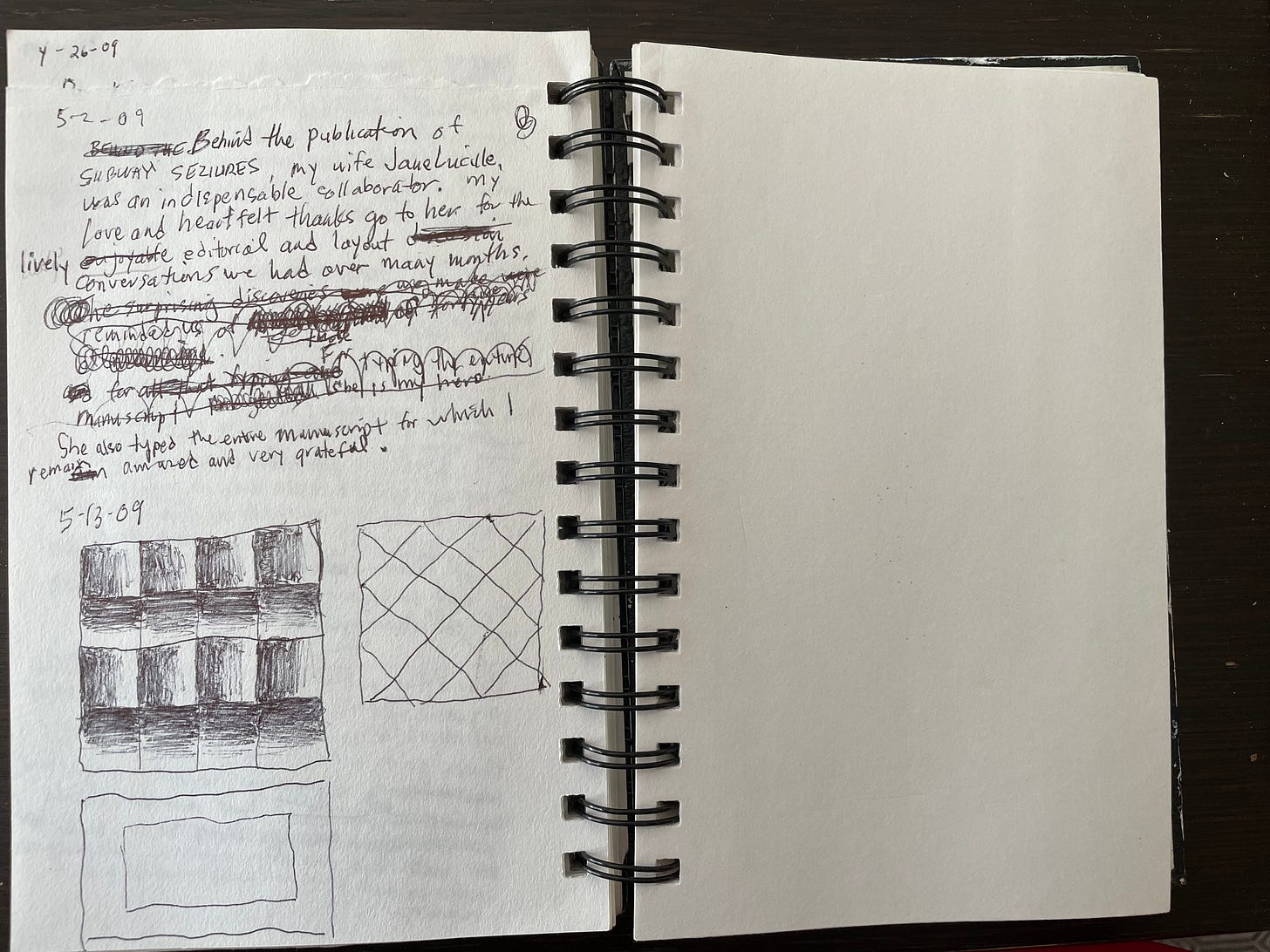

A prolific poet, Rinden also filled his notebooks with drafts and revisions of poems, many of which his wife posthumously published in Subway Seizures.

In late March of 1983, Rinden alternated between working a new poem and giving birth to “Slabism.” He would continue to experiment with this construction method for the next two decades.

Never without his notebook, Rinden sketched at concerts, on the beach, and during his travels.

Rinden’s notebooks provide unfettered access into every nook of cranny of a creative mind that never stopped churning. Six days before his death, he was still sketching ideas for paintings.

I have five of Thor Rinden’s slab paintings. They are beautiful. I think of him every time I look at them.