1/30/21

If a tree falls in the woods, most people think it still makes a sound even if there’s no one there to hear it. But technically, without ears to hear it, there is no sound.

Sometimes I think art is like this. If no one reads the novel, sees the painting, or watches the ballet, there’s no discussion or realization. No inspiration or joy. The work can’t realize its full potential.

I had these thoughts when Covid forced museums and galleries to shut their doors. I imagined all the installed shows that no one would ever see and wondered how the artists coped with their disappointment.

This issue features three of those artists: Kate Shepherd, Yasmine Diaz, and Sara Berman. All are at different points in their careers and make vastly different work, yet their stories share a compelling similarity.

The artists didn’t lament the fact that their shows closed early or never opened. They didn’t dwell on the critics or curators who never saw their work. They focused on what the show represented, the making of the work. What mattered was the problems they solved, the risks they took, the new techniques learned, and the questions answered. Not even a pandemic could diminish the power of their process.

—Maggie Levine

KATE SHEPHERD

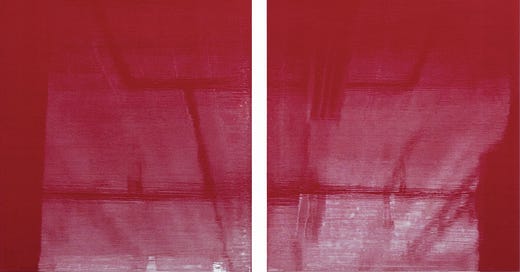

Kate Shepherd’s Surveillance opened at Galerie Lelong in New York on March 12, 2020 and closed the next day. You can take a video walkthrough of the show, watch her webinar with the gallerist Mary Sabbatino, and listen to her interviews with "Art in America," and on “Modern Art Notes.

Kate was also supposed to have a show at Hiram Butler Gallery in Houston. When that got cancelled, she worked remotely with the gallerist to create April, May, June, etc., etc., Upended Floor (Mud, Blood), a wall painting that visitors could see safely through the gallery's windows.

I

For 20 years, I have been making linear constructions on highly reflective painted surfaces. My goal has been to articulate space with the fewest lines. People sometimes complained that they couldn’t see the image past the light reflecting back unless they stood in just the right place, but I wasn’t concerned.

Eventually, I began to ask: what if I make the painting about that problem. How about embracing that light to find a way for the painting to make itself rather than applying a construction on it?

I started thinking about the visual experience of looking at layers of a pond: the surface, the water beneath, the reflection of the pond’s surroundings. I thought about what happens to our eyes and our experience when we look at each layer.

During a period of six years, I went through many ideas. To let go of a pre-drawn diagram of space meant I would have to bounce around in unknown territory.

The work I eventually did came along with allegiances to different painters. In this day and age, you can’t help rubbing shoulders with something that someone else has done. I was aware of Josef Albers, Henri Matisse, Larry Zox, to name a few. I had to either embrace these connections or swerve to another lane. At the same time, I knew my work was different than theirs. I add my own element of juiciness, personal experience, or emotional interaction. I want a painting to have a sense of humanity.

The funny thing is that even three months before the show opened, I was still finding my way to feeling one painting giving birth to the next

II

I titled the show Surveillance to mean watching and being watched. The painted panels and the viewer create the image. The paintings in the gallery's front room were screen printed recreations of whatever the paint “saw" (reflected) in my studio —for example a window or fluorescent lights. I wanted to get a sense of watching the emptiness a night guard might see on a monitor. In the other room, the reflective paintings transformed as you passed them. What you observed in one moment might disappear in the next.

There was something phenomenological about the work because it captured a purely visual experience. The show was grounded in a conceptual idea; it was more than just beautiful. This was new. I wanted it to be seen by critics and curators but this would be something that would prove to be impossible.

On March 12, we were already on guard about the virus. The gallery hosted a really nice opening which was attended by a small group of friends. And a day later, it was clear the gallery had to close doors. No one was sure what was happening, but I expected we’d just reopen in three weeks or so.

III

The show ended up being closed for months. Everyone at the gallery worked overtime to change how they operated, and they survived. And because of some online talks, I am becoming more relaxed talking about art. Eventually, the show opened by appointment.

Everyone who works at the gallery was so gracious, and there was a sense of peace. There's a scene in a French film where a woman makes herself the perfect omelet and salad, pours herself a glass of wine, and leaves the table without sitting down to eat. It made a big impression on me when I was a teenager.

On the last day of the show, ten minutes before closing, the critic Roberta Smith called and asked if they would hold it open. The fact that she was the last person there was such a beautiful bracket.

YASMINE DIAZ

LA-based Yasmine Nasser Diaz is a multidisciplinary artist whose practice navigates overlapping tensions around religion, gender, and third-culture identity. Her recent work includes immersive installation, fiber etching, and mixed media collage using personal archives and found imagery.

Yasmine’s solo-show soft powers was scheduled to open at the Arab American Museum in March of 2020. The work is still being “held hostage” as the show will run when the museum reopens. The video preview of the exhibition contains behind the scenes shots and Diaz’s commentary.

I

soft powers is my first solo museum exhibition. I'd had two small solo shows prior to that but never at a gallery or institutional space. So this moment was significant.

My family immigrated from Yemen to Chicago in the late 60s before I was born. Arranged marriage was standard practice in our community - there was no alternative. No women in our community lived independently from men. Your father was responsible for you and then your husband. I knew from a young age that I didn't want to be restricted that way and saw no path for compromise. At 19, I left with two of my five sisters. For almost 20 years, the three of us were estranged from most of our family.

My artwork had never addressed my background until around 2016, when I made a major shift in my practice. Though I had a lot of trepidation around coming out about my past, I chose to make directly autobiographical work. Telling my story was a way to lay a foundation for ideas I wanted to explore in the future, such as layered narratives of third-culture identity and code-switching.

II

The show at the Arab American National Museum was an opportunity to expand my work beyond my experience. Creating a fictional narrative allowed me to inhabit multiple points of view, reveal the complex inner worlds of my marginalized community and push back against reductive stereotypes.

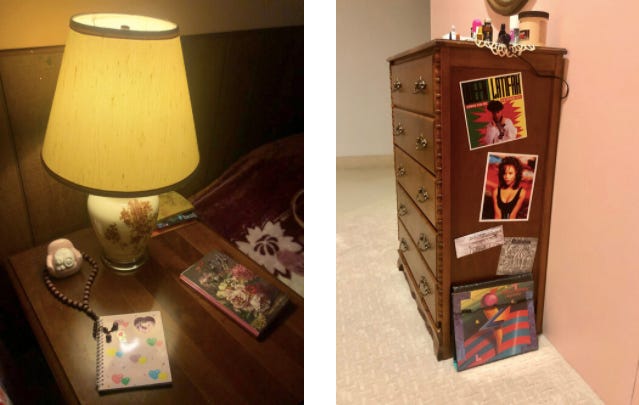

I'd created two-bedroom installations before, but for this show, I invented a narrative about two Yemeni American teenaged sisters in the 90's. Some aspects are similar to my life, some had happened to people I knew, and others I imagined. The installation's interactive elements shed light on what a teenager might have been going through at that time: I commissioned author Randa Jarrar to write excerpts for their diaries. You can also pick up the telephone and hear recorded conversations of Yemeni American women talking about their adolescence.

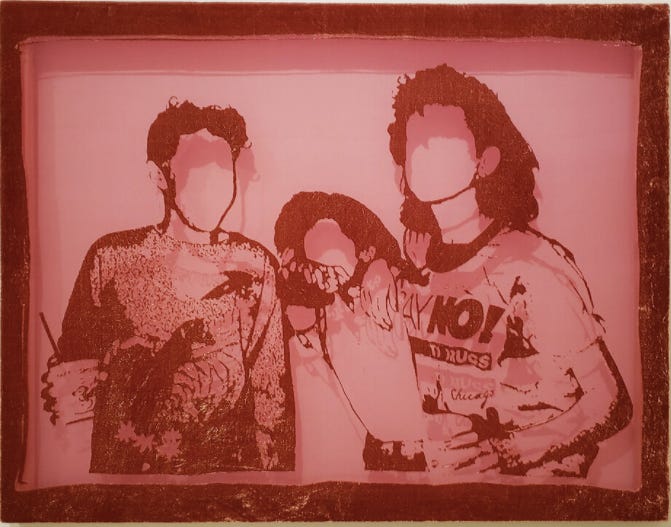

The second part of the show is a series of fiber etchings. The images come from my archives of photographs of Yemeni women.

Whenever I saw burnout fabric in the garment district, I'd feel nostalgic. The sheer material was popular in the 90s and is often used in a Yemeni style of dress known as a dir'. Burnout, also known as devoré, is done via a reductive chemical process, and after meeting a fiber artist, I taught myself how to do it in my studio. I was ready for a new technical challenge. It took lots of trial and error, and I ruined quite a lot of fabric in the process, but it was worth it. I love the result and the fact that the technique relates to the content.

III

The canceled opening was personally disappointing because it was going to be an opportunity for a family reunion. It would have been the first time my sisters and some other family members would have been together in over 20 years. Now I fear that the momentum may be lost.

Most artists would probably agree that the process is often much more important than the finished work -- that was very much the case for me with this show. Learning a new technique and producing a new body of work for the biggest show of my career was nerve-wracking at times. But those challenges made it all the more rewarding to see the finished work installed in the museum. I felt a huge sense of accomplishment, pandemic or not.

SARA BERMAN

A long and deeply held interest in the conversation between design, commerce, and identity informs Sara Berman's artistic practice. For two decades, Sara was a successful British fashion designer and consultant to fashion and design companies. In 2016, she completed her MFA and committed to painting full time and has exhibited her work internationally.

In December of 2020, Sara and ceramicist Alison Lousada conceived and mounted Scene Unscene at Gallery 46 in London. The day before the show was due to open, the city went into lockdown, and the show never opened to the public.

I

Before becoming an artist, I couldn't have predicted how my life would evolve to embrace making at its very core. Lockdown amplified this shift . Because I was home, I started weaving more than usual.

Weaving is meditation but with a malleable intention. I once read about a cellist who can reach a meditative place when he plays a complex piece that he knows well, a sweet spot where new thoughts and creative outcomes can play out. That's what weaving does for me: the boundaries, mechanics, and grid create a narrow lens and set of pre-established rules. Within that lies boundless options and outcomes.

When I got back to the studio, I found that the small-scale machinations of weaving were influencing the composition and scale of my work and shifted to making larger paintings. This change affected the relationship between my body and the canvas; I came at it differently in terms of mark-making, composition, and energy.

As the work threw up these new considerations, I was keen to see the paintings and the weaving together to consider how they related. The show was an exercise for me, a personal consideration of my practice as it exists in all its facets.

II

"Scene Unscene" refers to the unseen work of the woman in the domestic setting. Originally, Alison and I were thinking of calling the show "Air within Air," a reference to Dorothy Richardson's Pilgrimage. In the 1915 novel, a character argues that women are so engrossed in “the making of atmospheres" of which men are utterly unaware that "it's like air within air."

During lockdown, my role at home shifted from practical facilitator to someone charged with creating an atmosphere of safety and stability. This experience influenced how I rendered domestic space in my painting. Rather than occupying rooms filled with furnishings, the women began to hold the space. In paintings like Ooof!, they lean into the surrounding space to support their composition.

The materials I use-- clothing, lint collected from industrial dryers, and vintage bedding linens -- reflect my fascination with domesticity as an institution and social power structure. The linens are imbued with the history of bodies, as well as economic and political history. Their seams and mended holes denote years of use. When these linens become supports for my paintings, as in Tumble, I stretch the canvas away from its history and provide it with new space.

III

Of course, I was disappointed to have the show installed and never open, but it was primarily an opportunity to examine my practice. In that context, it didn't matter whether the show was seen or unseen.

The exercise allowed me to determine that I don't want to consciously burden each part of my work with some enforced legacy of another aspect of my practice. Sometimes what I make is relative to something else I have made, sometimes I may not make the connection until later, sometimes there is none. I am simply a maker.

Excited for move to Substack and the options to build community with your other readers. - Byron Thomas