ARTWRITE #9: The Art of Teaching Art

Ken Rush

11/13/20

Last week I took a break from ArtWrite because there was no room in my brain for anything other than the election. I also wanted to think about the direction of ArtWrite - the daily art posts and the newsletter. Like any creative endeavor, ArtWrite has evolved since its inception in July. Because it’s become more time consuming, I’ve lost traction with other writing projects.

From now on, the newsletter will be bi-weekly. I’ve got some great interviews lined up for the next few weeks and am excited to talk to artists in other creative fields about their creative processes. On Instagram and Facebook, ArtWrite will continue to promote work from living artists as inspiration for writers. While I won’t be posting responses as frequently as I have been, I still encourage others to submit their writing through ArtWrite’s website. Submissions don’t come in as often as I’d like, but it’s exciting to see what the art elicits when they do. Click here to read a lovely example from college student Lexa Krebs.

This week’s newsletter features an interview with artist and master art teacher Ken Rush. While I was never passionate about making art, Ken’s transformed how I looked at it when I took his art history class in high school.

The interview focuses on Ken’s teaching - his philosophy, relationship with students, and the importance of art in schools. In our conversation, Ken continually stressed the importance of access -- by putting a brush in a student’s hand, assigning a project that allowed for individual outcomes, or creating a physical space that invites play and invention. I love this notion because that’s how I see ArtWrite, as a means of access for writers.

Ken’s generosity is striking. It’s easy for teachers to get excited about students who demonstrate talent, but Ken was determined to reach as many students as he could. As a result, even those who did not go into art-related careers still appreciate his influence. Here’s what his former student Sarah Ross had to say: “Ken gave me the gift of seeing. He taught me to look at the world through the eyes of the greatest artists. Once you do that, you begin to see the world in your way and from your perspective. My particular world view is special to me, a skill I can tap into. The ability to see deeply has brought me confidence and joy.”

A teacher couldn't ask for more than that.

-- Maggie Levine

ArtWrite Interview: Ken Rush

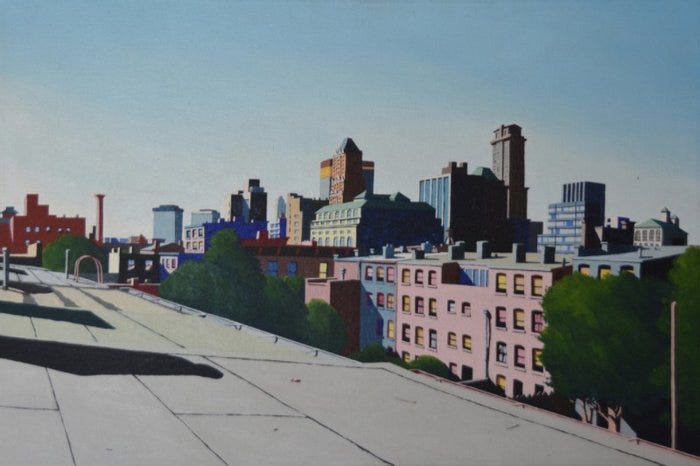

From his earliest paintings as a high school student to his most recent work,Ken Rush has focused on themes that allow him “to explore and look for different outcomes.” Recurring subjects in his work include the houses, roads, and rural landscape of New England, swimming pools, the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn, and the gothic architecture of Packer Collegiate Institute, where he taught high school visual arts and art history from 1978 to 2015. A virtual exhibit of Ken's new pool paintings opens December 3rd at Court Tree Collective.

I've known you for over 40 years, yet I don't know anything about how you came to teach or about your early teaching experiences.

It never occurred to me that I was going to teach. I got out of art school in 1971 and thought I was going to be a famous artist. I came to Brooklyn with my first wife and our new baby and quickly realized how hard it was to make money from my art. When I asked myself how I was going to earn a living, teaching came to mind. I got a job teaching elementary school art and pretty much cried every night for the first six months from frustration and exhaustion. I wasn’t doing much art and was overwhelmed by all these little kids.

I became friends with a gifted teacher who had gone to Bank Street in the late 60s and was the real deal experiential educator. He built a loft with a staircase to a padded reading area and mounted a gerbil run over the kids’ heads. His classroom was a wonderland.

Following Peter’s lead, I made the art room more like my own studio, a place for creative exploration. I embedded the workspace with hidden potential by offering a plethora of materials and processes. Naturally, I had to reorganize the space periodically, but when the studio fell back into disorder, that’s when the creativity seemed to blossom.

Through Peter, I also discovered the potential of unconventional materials. He introduced me to going to Soho on Thursday nights before the garbage collections. We’d pick up die-cut cardboard, plastic, just boxes of crazy material, and this stuff became the materials of my art room. It wasn’t so much painting or drawing. We did these Alexander Calder mobiles from the ceiling, and then the head of the school came in and had the maintenance staff take them down because they were a fire hazard.

high school paintings

Working with unconventional materials reminds me of a 3-part assignment that Kate Cusack, one of your former students, told me about. The first step was to draw a picture of your shoe, the next was to make a sculpture using a shoe, and the last was to make a shoe. No explanation. Just "make a shoe." Kate didn’t recall much about the first step because drawing didn’t interest her, but she vividly remembered taking apart her sneaker to make a sculpture. The logo looked like the wing of a fly, so she used the shoelace to write “Shoe Fly Shoe." When it came time to make a shoe, she found some window screening and built it from that.

The memory fascinated me because I could see the roots of Kate's career in the project. After art school, she went into costume design and did window display work, including constructing giant wigs from Saran Wrap for Tiffany. Today she has a gorgeous jewelry linemade from another ordinary material -- zippers. A career based on using unexpected, uncommon materials evolved from your assignment! It’s amazing.

I love it. Kate is referring to the possibilities that emerge from having that open-ended artroom and the excitement of discovery.

Multi-disciplinary artist Josh Slater also described the power of one of your assignments. After the class saw a Keinholz show, you had them do a take on his work. Josh said it was like “telling someone to do the opposite of painting a tree" and “to create chaos.” He'd never been allowed “to break something and glue something and produce something messy.” The experience was revelatory. Can you explain how these assignments reflect your approach to teaching art?

Over the years, I changed from being a teacher who would teach skills and then do the art to a teacher who believed the skills were learned by doing something more purposeful. I designed projects that allowed for different outcomes because each student had something unique to express, regardless of their artistic experience. Individual voices, no matter how undeveloped, can be encouraged and supported in art. Art encourages individual voices, no matter how undeveloped. Differences can be respected and channeled into strengths from which to build. The last thing I wanted to see was a class of students produce artwork that mimicked one model, one technique, one style, or one concept or feeling.

How did your own experiences as a student inform your teaching?

I had some early negative experiences. I got held back. After 9th grade, when I flunked two out of five subjects, I had to go to summer school. Fortunately, when I was a junior, my art teacher saved my soul. He set me on fire then left me alone. I discovered -- not that I would become an artist -- but that I was an artist. The only time I felt complete and accomplished was when I was doing art.

That's why, as a teacher, I would never say to a kid, “You can’t do art until your grades in Spanish or math are better. You’ve got to pass everything before you come into the art room.” No. My argument was, spend all the time in the world in the art room, and the other stuff will tend to get better. Kids who don’t do well in academics are not usually happy. But if they achieve in the arts or athletics, they can build on that.

I tried to provide all my students with skills and an authentic art-making experience, accepting that, for some, it might be the last one of their life. But that was ok. Not all kids got set on fire as I was.

Your former students have come up with some unusual ways to describe your positive energy. Kate said you “embody a scribble,” and Josh referred to your “hyper Mr. Rogers kind of vibe.” All kidding aside, this passion, what Kate referred to as your “enthusiasm for art, for life, and teaching,” is something your students have never forgotten.

My strength was my unbridled conviction that what I was doing was important, and that was art, that what the kids were doing was important. But being unerringly supportive was my weakness as well. I’d get evaluations from kids that said, “I learned so much blah blah,” and then I’d have kids who said, “I didn’t learn anything because Mr.Rush can’t help being just a cheerleader.”

How did you handle having students with a wide range of needs and abilities?

When you’re teaching, there are many approaches, but the two extremes are to respectfully leave a student alone with their work and allow it to develop or coach a student so that they can experience progress. I’d say that 80% of my energy went to kids who needed a lot of support, coaching, and even coaxing so that they could discover their particular outcomes and talent.

You’ve also got to recognize the kid who needs to be left alone, that they are in their own space and safety and time. And to give them the feedback that they are willing to acknowledge and not the feedback you may want to throw on them. Otherwise, you can push them away.

Kate and Josh both mentioned how meaningful it was to them that you kept work from previous students in the studio and that eventually, the collection included work of theirs.

The walls of the art room always displayed student work. I would rotate most of it democratically so any student could feel represented. There was also a permanent collection of select work, often pieces that provided a unique example for the next generation’s students. These works hung for decades and represented the students who had the greatest impact on the program.

What advice did you give to students when they were struggling?

At my best, I was able to be sensitive and open about what they might be going through and allow them to have some voice because often they couldn’t articulate their struggle. If you have a student whom you’ve seen accomplish a good deal, and they’re going through a fallow time, the best thing you can do is acknowledge that that’s part of the normal cycle and not become another hysterical voice in their life saying, “why aren’t you getting an 800 on the SAT?”

After you left teaching to commit to being full time in the studio, you went through a difficult period. Can you talk about that and how you got out of it?

The first summer, I had a show, sold a lot of work, and was working every day. And then the following September, instead of going into the studio, I experienced a sort of grieving. I had to come to grips with this huge shift in my life’s rhythm and purpose. Our children were grown up and no longer at home, and my structured and exciting days at Packer had ceased. Yes, I’d been an artist, but I had been teaching or been in schools almost uninterrupted for 65 years. My identity felt fractured, and the doubts about my art and ability to continue meaningfully as an artist overwhelmed any sense of purpose. It was agony.

I finally started to paint mechanically. Slowly, slowly, feeling began to come back into my body. It was like having an accident and going through physical therapy. You don’t think you’re ever going to get out of it. But slowly, I began to have glimmers of joy.

Thank God I had my wife, Chris, who patiently waited for me to emerge from the depression, just as I had so often waited for students to find their creativity. It’s amazing how creative people deny themselves the very thing that makes them feel alive.

Why is it valuable for someone who doesn’t see herself as an artist to take art classes?

If kids become authentically involved with a process in the Arts where there’s an outcome they can see, it’s incredibly satisfying to the soul. An immersive theater experience, perhaps performing in only one high school play, can sometimes be a person’s most poignant school memory. I saw many kids who tapped their inner artistic self for 3 to 6 months, maybe for even a year, and it didn’t matter that they weren’t going to be an artist for life. At the moment, they were artists.

The arts provide a vehicle for a combination of intuitive and spontaneous results and intellectual and emotional processes. These are hard to access in non-arts disciplines. They provide a space for these processes to develop and for outcomes to be shared. This development helps in the maturation of all people, not just artists.