ARTWRITE #6: A Visual Diary and Exploring the Five Senses

Becky Lewis, Bellamy Burke

10/16/20

On Sunday night, I posted ArtWrite for Kids' first submission, "The Inspirational Vines," written by my 10-year old neighbor, Bellamy Burke. Her story about an artist who finds inspiration in a jungle was prompted by "Paradise," an abstract tangle of watercolored lines in shades of green. I fell asleep thinking about how excited Bellamy would be to see her work, paired with the painting, published online the next morning.

At 3 AM, an email from the artist, who lives in Berlin, woke me up. I didn't have permission to use the image, and she wanted me to take it down. How could this be? I always made a point of getting permission before posting an artist's work. After double-checking, I discovered that the artist was right. I'd screwed up. My apology did not change her mind.

ArtWrite without art felt wrong. Could I find a substitute? Maybe Henri Rousseau. He painted jungles scenes. But I quickly learned they all include wild animals, and Bellamy's story only has a bird.

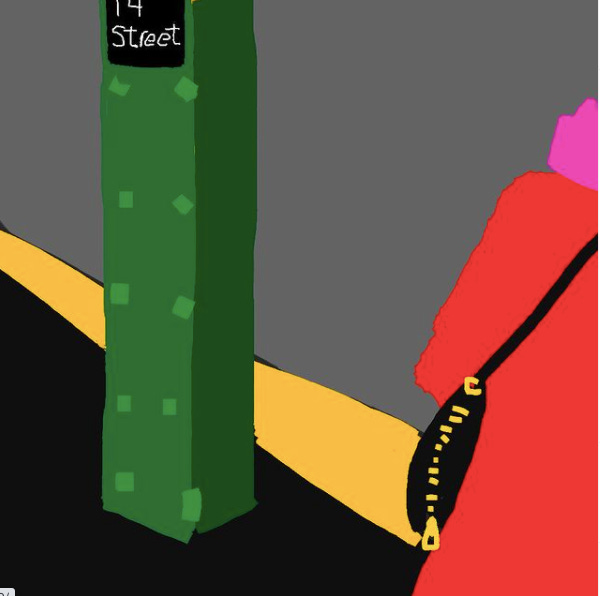

I emailed Becky Lewis knowing that she does quick, vibrant drawings on her phone. "Do you have something jungle-y? With lots of vines and a bit of red in it?" Thankfully, less than 24-hours later, Becky came through. You can see her drawing and read the story here.

When you're done, scroll down to read my interview with Becky and to learn about the three steps of Bellamy's writing process.

-- Maggie Levine

P.S. Bellamy likes Becky's image more than the original.

ArtWrite Interview: Becky Lewis

Memoirs and autobiography are not the same. The writer and critic, William Zinsser, explains the difference: "Memoir isn’t the summary of a life; it’s a window into a life, very much like a photograph in its selective composition. It may look like a casual and even random calling up of bygone events. It’s not; it’s a deliberate construction."

Becky Lewis uses her drawings "to catalog times, places, and people in my day to day life," but her visual diary has the richness and focus of a memoir. Her images -- a chair with charming tassels, an arrangement of vases, fallen blossoms, the zipper on a bag -- reflect her particular sensibility and provide an intimate "window into a life."

Explain why drawing on your phone works so well for you.

One of the things I love about working digitally is that I can add, subtract, and layer, and then carve away to make shapes and textures. I am constantly editing while drawing, erasing, adding layers. It is an enormously freeing medium.

I also love the immediacy of the phone, that I can discreetly observe and record in the palm of my hand. And, unlike a sketchbook, I have access to color to express the emotion of that moment.

How has your process with digital drawing evolved over time? Did it take time for you to learn the potential for the app?

My ease with working this way has definitely increased over time. The earliest images seem very crude and flat. Also, the technology has improved. My early images are also very low-resolution, something that Brushes corrected over time.

Your phone images are visual note taking, a kind of truly portable sketch book. Does this work get translated into work off the screen?

In the isolation and uncertainty of Covid, I have been thinking a great deal about the value of community. Not just friends but everyone we come across in our day to day lives. I wanted to create a feeling of a community as a garden. Every day I go into my studio and paint individual flowers to represent that community that I miss so much. And to complete the cycle, I mail them out to the person who inspired them. This was something that I could only do with intention, in paint, not digitally.

At the same time, I felt I had to respond to what was happening in the world. Furious over the senseless murders of George Floyd, Elijah Jovan McClain, and Breonna Taylor, I used the immediacy of the phone and digital drawings to create a series of black and white flowers in memoriam. In the Brushes app, I was able to duplicate the drawings, erase the black, and fill in the white to create identically opposite images. The flower was the same, but when it was white on a black background, it was worlds apart from the reverse image of the black flower on a white background.

At what point did you begin calling yourself an artist?

I went to college to explore and was fortunate to attend a once in a lifetime liberal arts college, Kirkland, the women’s college for Hamilton College. Everything was possible at Kirkland – the artists were also mathematicians, the biochemistry majors were musicians; there were no grades or tests, and the lecture hall was a red-carpeted pit. In this environment, I could carve out my identity however I saw it. By the time I graduated, I knew that this would be through making images.

Describe New York City when you got out of college.

I came to New York with the intention of letting the city educate me. The art scene in the late ’70s, early ’80s in the East Village, and even Soho, was filled with energy. Music and art were aligned. Nightclubs, performance art, and studios were often the same thing.

There was a wonderful "let’s put on a show!" approach. Pat Hearn, Nicolas Moufarrege, Ann Magnuson were all curating shows around themes of the moment: speed, the resurrection, bondage, road signs, fast food culture. There were shows in subway stations, museum bathrooms, and storefronts. Rents were relatively cheap, and I was lucky to be awarded studio space at PS 1 and the Clocktower.

What was your work like at the time?

I was painting large canvases using whatever medium was at hand; house paint, acrylic, spray paint. It felt important to paint what I knew, so I painted horses. My father was a horseman, and I had ridden and been around horses most of my life. I loved the incongruity of painting polo ponies, hunt meets, and steeplechases in spray paint and showing the work at the same in the windows of Cartier and in the Bronx at ABC No Rio.

Why did you leave NYC?

By the mid-80s, things were a lot more expensive and competitive. AIDS decimated the community, and what was once endless fun was sad. It seemed a good time to leave and find a place where I could draw for myself instead of for shows. I moved to Boston, and while I showed my work occasionally, for the most part, I was more interested in filling sketchbooks rather than putting work up on walls. I am relaxed about what makes someone an artist. I don’t need a studio or a tower, all I need is my phone or a sketchbook.

What advice would you give to an artist who is struggling to move forward with their work or who feels blocked?

Don’t think too much just let your hand go.

What parts of the creative process are the easiest for you and why? Hardest?

The easiest part is telling the story and finding the elements that tell it – a shoe, a bowl, the pinky ring.

Being public and sharing is more difficult. My work has been very small and intimate in scale and subject. I am not that interested in showing my work. I am more interested in the process of making it, using the drawings to catalog times, places, people in my day to day life. I have enjoyed putting the images out on social media because I like the conversational aspect of it – “look what I saw today.” This is what feels important.

I'm so glad you're emphasizing the importance of process as that's the whole point of this newsletter!

Using ArtWrite To Explore The Five Senses

STEP 1: GENERATE MATERIAL

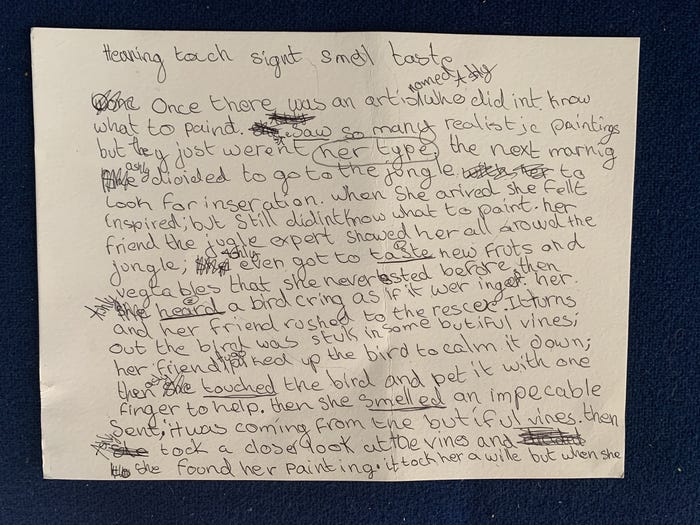

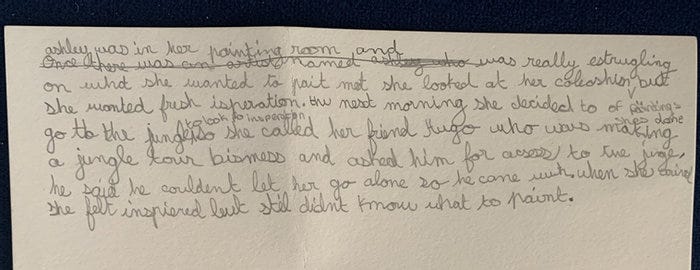

Once Bellamy chose her image from the ArtWork For Kids page, I told her that she could write anything she wanted - a story, a poem, a description, a letter, a diary entry, a play - anything. The only rule was that she had to use all five senses.

I had Bellamy list the senses at the top of her page then left her alone for 20 minutes. Everyone has a different attention span. Ideally, you would write until you have nothing left to say. Bellamy wanted to keep going and wrote for another 10. Before reading her writing, I had Bellamy underline and number where she used the five senses.

It was immediately clear that Bellamy was telling when her character employed a sense, rather than showing her character's experience of the sense.

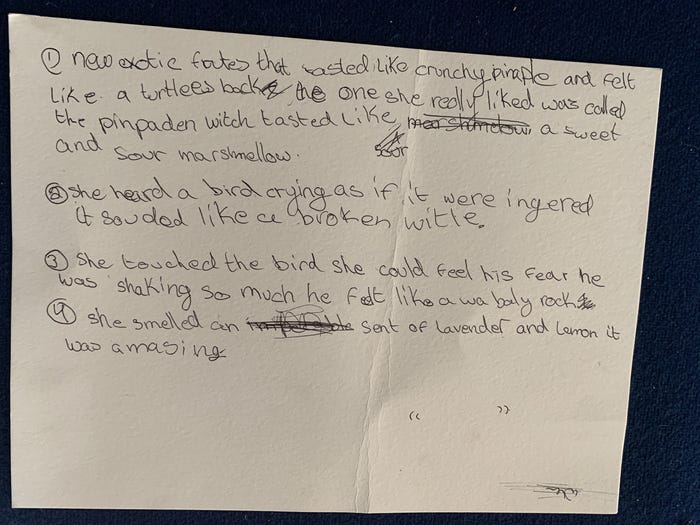

I read each of the five sentences aloud to her, each time overemphasizing my frustration as a reader: "What did the fruits and vegetables taste like? I'm dying to know!" And "you said the scent coming from the vines is 'impeccable,' but what does 'impeccable' smell like to your character?"

Bellamy began to explode with ideas. I quickly cut her off and handed her a piece of paper. "Don't tell me. Write it."

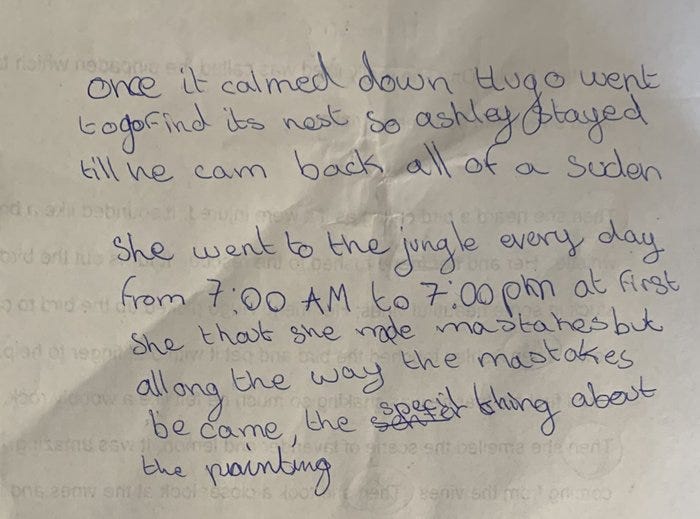

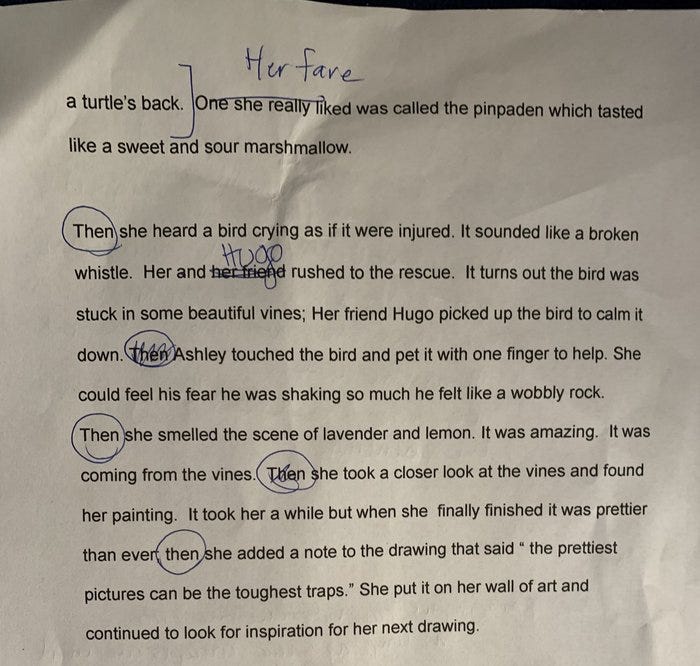

Her revised sentences were much more vivid. My favorite is her description of the injured bird who "sounded like a broken whistle" and "felt like a wobbly rock."

STEP 2: CLARIFY & DEVELOP

In the second session, Bellamy focused on revising the parts of her story that needed more clarity and development.

For example, her story originally opened with a variation of "once upon a time," and there was no sense of a setting. "Where is Ashley?" I asked. "What is she feeling? Put us in the room with her."

Bellamy also rushed through a number of important moments. Her character goes from petting a bird to smelling some vines to solving her problem in all of two sentences. That's inevitable in a first draft. I had her go back and develop, aka flesh out, the sections that were missing such as what happens between when her character finds the bird and when she makes a painting.

Step 3: EDIT

Before our 3rd session, I typed up Bellamy's story so she could see it as a whole. Seeing their work typed also makes kids feel professional.

I had Bellamy circle every time she used the word “then” and remove the ones she didn’t need. "Then" is a remnant of the first draft when your hand can't keep up with how quickly your brain is coming up with ideas. No big deal. You just take them out later.

I chose two other editing issues and addressed them one at a time so Bellamy wouldn't feel overwhelmed.

Paragraphs

Belly defined a paragraph as "four sentences." When I explained that it could be 1, 10, or 100, as long as the sentences all related to the same topic, she got the concept and went back to she where she needed to indent.

Run-ons

I read each sentence aloud, and whenever I hit a run-on, I literally ran the words together so Bellamy could hear where she needed a period.

The last step was for Bellamy to come up with a title:

"What's the story about?" I asked.

"Vines."

"What about them? How do they help Ashley to solve her problem?"

"They inspire her."

"Can you use 'inspire' with the word 'vines? Or another form of 'inspire'"?

"The Inspiring Vines. No. The Inspirational Vines."