10/7/20

I did a lot of thinking and writing about the past this week. The death of designer Kenzo Takdaka and Mills Brown's glorious patterns reminded me of what it felt like to be 18 and discovering Paris on my own while researching Katie Merz brought me back to when I was 12 and broadening my world through new friends from outside of my school. One of those friends was Katie's younger sister, Amy.

I never got to know Katie well, so I've been delving into whatever I can find about her online. I was especially struck by what she said in this video about how she came to make art:

"My parents let us run wild. I grew up in Brooklyn, in the city, and we played on the street a lot, created things, games, buildings, drawings. And in the backyard, there were bizarre things that we would make -- just worlds. I realized that this free way of playing and my magical thinking was a gateway to become an artist."

This explanation definitely makes sense to anyone who was fortunate enough to have gone to the Merzs' Willowtown home in Brooklyn Heights. I still remember how radically different it felt from the dark, vertical 19th-century brownstones that many of my friends lived in. Designed in 1963 by Katie's parents, Joe and Mary Merz, the open, light-filled space was probably the first example of modern architecture that I'd ever seen. I was awestruck.

Katie describes herself as ”Born and bred Bklyn" and cites Brooklyn as one of her influences. I don't know anyone who grew up in Brooklyn who isn’t proud of their roots, and that led me to explore how it’s possible for people to identify with a place that's so huge. You can read what I came up with here, but I think Katie does a much better job of explaining it when she talks about Brooklyn's "street fluidity" in the interview below. I'm so grateful to Katie for sharing her background and process.

Lastly, a quick shout-out to Sara Rahbar. Choosing which of her 59 American flags to post was incredibly difficult. I settled on Flag #1 but urge you to take a look at the entire series. It couldn’t possibly feel more relevant than it does now.

-- Maggie Levine

ArtWrite Interview: Katie Merz

Katie Merz is an Artist, Illustrator, and Muralist who has "elevated simple, cartoon-like line-art to a level of social documentation and commentary that transcends the best street artists of the past 35 years.”Her most recent project, a 12-story, 120 foot tower on the campus of Ursinus College entitled "Live the Questions," is a “provocative narrative of life experiences that have been impacted by a global pandemic, racial injustice and other life-defining moments.” Make sure you check out the video of Katie's windy last day at the top of the tower.

Tell us about the tower project at Ursinus.

I worked with Deborah Barkum, the curator at the Berman Museum. Before Covid hit, the content on the smokestack was to be about Collegeville and Ursinus. Fairly broad and general.

After Covid, the seniors had to leave campus which was a huge blow to their spirits. We reformed the intention of the smokestack so it would be a monument to the students’ unfinished semester. We sent out an open call to the seniors with a set of questions about their final semester and what they would miss about the school.

Can you explain how you translated these interviews into the symbols, shapes and rebuses that you used in the piece?

Decoding the interviews was a process of deduction. I break the language into lists of words and images - very basic signs and symbols of language that can be read by anyone. Almost like ancient emojis. These words and images became the prompts for the drawing that would cover the entire cylinder to create a non-linear, abstracted, 3-D story of the seniors’ lost year and memories.

MORE SMOKESTACK VIDEOS & IMAGES

Can you explain the below video of you “practicing for the smokestack?"

The practice in my studio for Ursinus was about training my arm to jump up to a scale that was unimaginably gigantic. Not until I got to the top of the smokestack could I understand how giant (ten feet in diameter) each object would have to be read from 120' down and a mile away. The book that I would draw in the training video would become one of the smallest objects on the smokestack.

Your style is instantly recognizable. How did you arrive at it?

I went to a dilapidated art residency in rural Nebraska where I riffed off of my surroundings. I wrapped the side of an old barn in black roofing paper to patch a raccoon hole. This surface, reminding me of an asphalt street, was seductive to me. I decided to tag it using a white oil stick. I interpreted, in hieroglyphic form, a Rilke poem that I was reading. This transported me back to my childhood—drawing on the street again—but this time I was doing it on a wall, using language, and changing the surface of a building. It was language, architecture, and a binary system all at once that looked like a non-linear blueprint of the inside of my mind at any given moment—as well as patching the raccoon hole.

You say that you have no plan when you draw, that it’s “a spur of the moment process that reflects the kinetic ordering of [your] mind’s images, associations and feed.”

Can you put us in your head and give us a sense of what this feels like, especially the “kinetic ordering” aspect?

The definition of drawing is pulling from one place to another as in “draw water,” “draw an idea from,” “ draw your attention.” It feels like I'm pulling words, symbols, and signs out of a hard drive in my head that is specific to each project. These prompts are my structures. My architecture. I think of what I am doing as The Architecture of Language. I can compare it to jazz: you have a structure and then break that form and then reform it into another set that you break. And then you step back and it has its own form.

At Ursinus, I had lists of words taken from the interviews with the students. I started to freestyle onto the smokestack from all of the content I had gathered from the interviews and from the experiences I’d had there (and then the students would come by and give me more content). I am, in a way, collaborating with words that I associate with the site or that are offered to me by.

I can compare it to jazz: you have a structure and then break that form and then reform it into another set that you break. And then you step back and it has its own form.

To answer your question about ordering: it feels like finding the right pitch in music or the value of the spaces in between things. I took violin for eight years when I was a kid. So much of my time during practice was spent trying to hear and play the right note, to understand the perfect pitch and to notice the infinitely different spaces between the varying notes. It is a very synesthetic practice. Even though I hated practicing the Violin, I realize now that it was my highest education. I am doing the same practice while drawing - but I am doing it backward and with line.

In your video introduction to the class of 2020, you describe how the “free way of playing” that your parents encouraged during your childhood led you to become an artist, even though you never thought of yourself as one. At what point did you decide you were an artist and has your understanding of being as an artist evolved over time?

This feels so strange to answer. I thought something was wrong with me for a long time. When I was a kid I think I had an overactive imagination and that scared me. I thought I was not connecting to the “ real “ world. So I would draw at night in my room, and these intricate, crazy drawings were reflections of what I was imagining. They led me to feel that I was okay. That these imaginative places could exist. So maybe it was then that I realized that I had this life long companion in my imagination, and this companion was called art.

It wasn't until years later that I actually was labeled as an artist, but I still don’t know how that word could describe it all.

If someone comes from a background that does not encourage creativity, how would you suggest they develop it?

I would give them a project of perception. It would start with the practice of just noticing. I would have them notice all of the shadows that you see during the day. Or I would ask then to list their day backward, or to only use the weaker hand all day and see how that felt.

These are practices in notating how your mind works and how it senses life. I don't think it's about art making. It’s about noticing how your mind works and being comfortable with it because at level one: it is like no other mind out there.

Can you be more specific about what Brooklyn means for you and how it translates into your work? When you think Brooklyn - what are you visualizing?

Brooklyn was very free form when I grew up in the 1960s and 70s. There is humor here. Every street really is a story, and the people that make up a street are the characters in a play. This place is wildly performative.

In our generation, there was no pretense. Brooklyn was not an adjective that could offer you a portal into a fantasy life with brownstones backdrops. It was DIY. Streets were open, and the money was not at a premium. It was about the people, and the streets, and the action between the two.

Growing up in Brooklyn in the 1960s embodied a street fluidity that you can take anywhere. I could write a thesis on this. Maybe that's what the buildings are about ... a thesis about the interaction between the street and the people.

How do you logistically and artistically juggle it all? For instance, you just finished the project at Ursinus, and if you don’t have another commission, how do decide where to put your attention? Do you have a studio practice (or version of it) that you go back to? Do you still draw/do cartoons? What’s next?

Wow. Yikes. Hardest question.

(That's because it was four questions).

Next is making sneakers for a friend's pop up, and I have a pair of custom Converse coming out in Japan in a month. Really excited (see below). I’m doing an exterior job in Austin and also an EMOJI alphabet in my own drawing style, and I’m making a chalk animation with my friend next week, and a few other small interior commissions. And I'm working on getting my work licensed onto things, so that will be interesting and new.

I love going to my studio (even if I don't know what I’m doing there ), and I love exercising, and I hate stress, so I try to keep all of them feeling like they are the same activity (biking, drawing, walking dog, making work, etc.).

I don't do the small gouache drawings anymore because I have hundreds of them, and I am done with that interior practice for now, but the cartoons have turned into my buildings, so it is all an extension of itself. It has just changed scale and form.

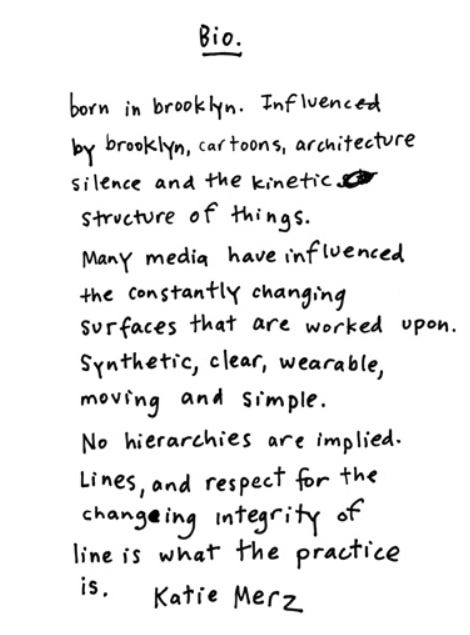

Most artists publish long, wordy statements about their work. Yours is not.

I do not like verbose art speak. I have a low attention span for the artists' over-explanation of deadly stuff. I would rather just see their work. This BIO is my sharpie shorthand longhand of me. I was going to make it more formal but that seemed like too much work -- this says it all.

I was struck by the absence of a subject in the phrase “surfaces that are worked on.” Did you deliberately take yourself out of the sentence, or am I reading into it?

Yeah, I didn't want a me in there.

Can you expand upon what “respect for the changing integrity of line” means to you?

The surface changes, and my mind adapts to the different surfaces that I end up working on, and the line connecting the different approaches of thought, or trains of thought, holds it all together. I have so much respect for the mind's natural thread of continuity. I keep following it along to the next spot, and I look for integrity in the practice of continuing something when I have no idea where it is going.

That sounds a lot like what EL Doctorow says about how "writing is like driving at night in the fog. You can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.” If you just keep writing, you will get there.

That is it. I think about Ginger Rogers. She had to do everything Fred Astaire did but backward and in heels.

What aspect of the creative process is the easiest for you and why?

The easiest is drawing and saying yes to everything.

Drawing is superfluid and fast. I am not judgemental anymore ( in my work ) That makes all of this practice really fun. I like problem-solving too, and in a secret way, I like making mistakes because it has the same feeling as doing something really good.

I like getting over a fear. It's like slipping through a mirage.

What aspect of the creative process is the hardest for you and why?

Saying no. And the build-up to a large job. I have been doing these big exterior projects for only four years, so the stakes ( logistically) are much higher than being in my studio by myself. I get horrible stomach pains and anxiety before a job. I always end up on the other side of this anxiety, but the anticipation brings on a full internal meltdown.

The hardest part is starting anything. Ugh, I can't stand the start. I am doubtful and tired and contracted, but I try to curb that sour mood so I don’t ruin the spirit of the situation.

Finally, are you a reader? What kind of texts do you gravitate to?

I am becoming less of a reader than I ever have been. It is so random at this point. I read Pearl S. Buck’s The Good Earth this year, and I was floored by what a classic, archetypal story of life it was. Right now (this is ridiculous), I am reading Meririam-Webster Dictionary in a random way so I can bypass story and get right to the point.