ARTWRITE #29: IN CONVERSATION

Alexis Rockman and Jenny Offill

On June 26, I moderated “Facing an Uncertain Future: A Conversation with Jenny Offill and Alexis Rockman.”

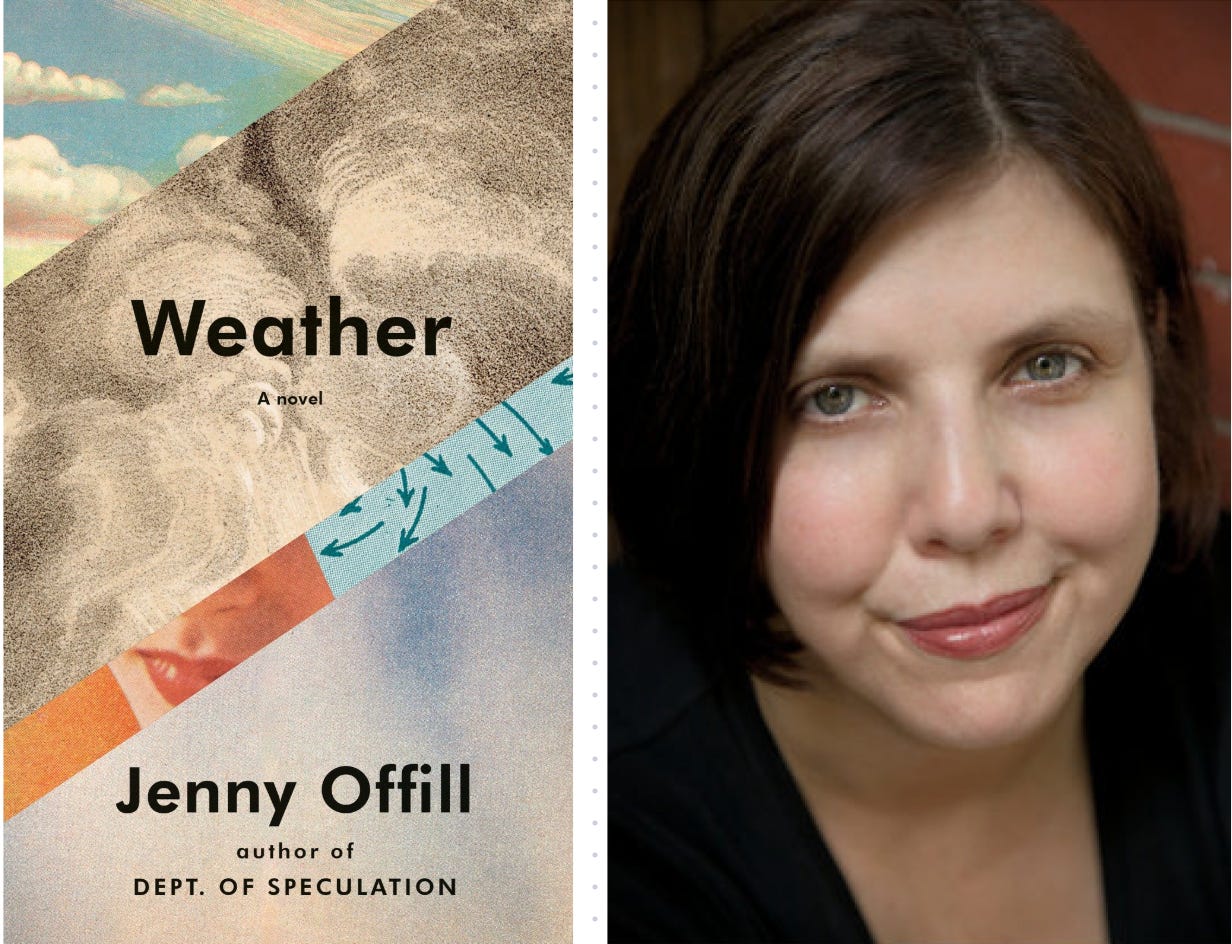

Rockman, whom I featured in my last issue, was one of the first contemporary artists to address environmental issues through his work. His works depict a world shaped by human excess and ecological collapse. Weather, Offill's 2020 bestselling novel, explores climate collapse by asking, “Can you still just tend your own garden once you know about the fire outside its walls?”

Despite their shared concern about climate crisis, the artist and writer work in radically different scales. Offill’s recent novels, narrated in her signature fragmentary style, capture her characters’ interior thoughts and are intimately focused, while Rockman’s meticulously detailed paintings often favor a wider lens and rarely include people.

Below is a distilled and edited transcript of the conversation. The full recording is available on YouTube.

On Origins

Alexis: As an only child with distracted parents in a place of concrete and glass, nature and the ideas of nature—the dioramas at the Museum of Natural History, the zoos of New York — were places of enchantment. They were an oasis that kept me from despair. I drew the things that I loved, got encouragement from my parents, and sold a drawing for a quarter. Here we are.

Jenny: The novel Weather came out of conversations I'd been having for 10 or 15 years with my best friend who's a novelist—Lydia Millet—and also an environmentalist who works for the Center for Biodiversity in Tucson.

I started reading comparative mythology and came across this idea that in different mythologies around the world, there are very few examples of a slow apocalypse. We have lots of myths about sudden disaster, but none that convey the idea of "slow violence.”

The philosopher Timothy Morton called climate change a "hyperobject"—something so big that we can't even get the sense of it. I noticed that I could think about it intellectually, but I couldn't feel it. I thought, well, how do you scale that down to a human level?

On Each Other’s Work

Jenny: I saw Alexis’s work at the Brooklyn Museum many years ago. I’d been reading Bill McKibben's End of Nature that talked about things that are no longer here, the kind of megafauna we've done away with. I was interested in the idea that someone could project into the future, so it was great to see that being done in Alexis's work. The element of speculation fascinated me.

Alexis: There is something in Jenny's work. A sort of gleeful fatigue of people. There's a moment in Weather about societies going through trauma or some horrible event, how they cope or recognize it.

Click post title at top to watch video in browser or Substack app

On Truth

Alexis: Truth doesn't mean a damn thing in this culture anymore. It's about storytelling. After I did "Manifest Destiny," I went around Hollywood trying to pitch climate change stories. I pitched it like The China Syndrome—that did to nuclear energy what I wanted to do to climate change. No one gave a damn. They looked at me like I was crazy.

I've worked with scientists on projects like "Manifest Destiny" and "Oceanus"—those are really institutional projects, and I wanted to bring scientific credibility. I used to believe that if we could educate and be activists, that would change people's minds. Little did we know that tribalism is destroying us.

Jenny: There's a problem with the story of climate crisis because it's like, "Oh wait, look in the mirror—I'm the villain, you're the villain, we're all the villain." If you look at a movie like Michael Clayton, which is a really successful paranoia movie, the conspiracy is personalized.

Science, by its nature, has to have precision in language, but the language is full of frustrating terms. "Positive reinforcement loop"—not a good thing, but it sounds like one. Even when people talk about how "the changes are baked in,"—sounds sort of delicious, but it means something quite apocalyptic.

There's a really great book called Don't Even Think About It: Why We Won't Talk About Climate Change by George Marshall about the need to use different words for different groups. If you talk to a Christian group, you say "stewardship." If you talk to hunters, you say "conservation." But we've entered such a post-truth world that those problems of science communication aren't even what we're dealing with anymore. Denial isn't really the problem—people know what's happening. What it would take to deal with it just isn't appealing.

On the Question of Hope

Alexis: First of all, I love making my work. If I had all the money in the world, I'd do it anyway. And I love what I make my work about because I'm fascinated by it, and that's how I cope. It gets me out of bed. And then I also make a living from it, so those are very motivational things, to say the least.

In terms of hope, I don't know what that means. Sometimes I look in the mirror and wonder where the cancer's hiding. We all have these dramas playing out invisibly in our own bodies, whether we know it or not, and it's happening on every level of this planet. You better enjoy it while you're here.

Jenny: The question of hope always comes up, but maybe it's too narrow a word for what we need in this moment. I think we need something closer to courage and perseverance.

There's a version of hope that's tough-minded and doesn't assume one particular outcome. In The Plague, Camus called it “active fatalism"—going forward trying to do good with the information, but realizing you don't know how it will turn out. We all want something that will reassure us, but I think that it's important to kind of live in the mystery of what's happening here.

We don't have enough humility about how the world works. If we can step back from trying to be sure about the outcome, we can live in this moment and see what is wondrous about it. I came out of Weather much more hopeful than I went in because I saw all the things people were doing around the world that were thoughtful and making a difference.

On Parameters and Constraints

Alexis: How do I start a painting? I think about the greatest paintings ever, and then I'm thinking, where is this going to fit in the canon? Then, I decide what the rectangle is and go from there.

The great thing about being an artist—and a lot of people are mystified by what an artist is, but it's the same as a writer—you set up your parameters and then you try to solve it and make the best version of what that is.

You start to think, put it together, think about it, put it away, look at it upside down. You think you're a genius, then it's terrible. You just have to be honest with yourself and go back and forth.

Jenny: I think that with anything I've ever worked on, the process is really just swinging from grandiosity to self-loathing, grandiosity to self-loathing. If you're lucky, you don't land on either side at the end of a project.

For me, with Weather and my first novel, Last Things, I felt the same way. It's important to me to get the science right, so I make sure of that by talking to people. With Weather, I noticed that whenever you read anything about climate, eventually you hit a wall of figures and numbers. So, I made myself a constraint: No numbers. And then I broke it because I wanted to put in one number: the year that New York City is expected to go into climate departure, which is when the temperatures no longer match what we historically have had. It's frightening to think about.

On Process

Alexis: My process has changed over the decades. It used to be tracing paper and pencils—big sketchbooks. Now, it starts with folders and words, then a diagram with arrows. I flip it around, put it into Photoshop like Post-its on a board, just trying to get a feel for it. Sometimes it's taken four years to figure things out.

For institutional pieces that are 24 feet long—because you have so many creatures in each piece—I have a list before I start. For an upcoming project about the ice age before Europeans arrived in the Middle East, I have a list of narrow-lipped rhino and all the things that lived there before humans arrived.

Jenny: My process looks like the most inefficient, silliest way to write a novel. Every reasonable writer writes in drafts. That's how you're supposed to do it. For some reason, I have to get a section and the language the way I want it before I go to another section. I don't always write chronologically.

First, I try to make the cadence sound right. Poets understand that, but it's a backward way to write a novel. It's like doing a jigsaw puzzle without the cover and wondering, Is it cats? Is it jelly? It takes a while to constellate together.

The danger with fragmentary form is randomness. For me, it's a long process of moving pieces around and letting time be the editor. After a while, a lot of fragments lose their radiance and don't seem as interesting, so I remove them. But some stay and have a magnetic force together, and that's how the story is built out.

On Artists vs Writers

Alexis: I think that there's a tradition of a person alone in a room that makes something, and you have one object, and it's take it or leave it. And with a writer, there are words. You're working in a system with an editor, an agent, a publisher, and there are steps, like a cow becoming a steak.

Jenny: To me, the big difference between being an artist and a writer is that the artists have much more fun and are much cooler. A friend of mine who is an artist asked me, "Well, what do you do on days when your writing is just going so terribly?" And I said, "I just think to myself, like, 'I'm a bad writer. I shouldn't write. Why don't I see if I can become a primatologist?'" And I said, "What do you do?" And she said, "Oh, I just stretch canvases." For me, stretching a canvas is often research, typing out really interesting research.

Alexis: To be clear, I definitely am not alone in a room.

Jenny: That’s what I mean. It’s much more fun.

Alexis: I talk to my friends all the time. I can listen to gangster rap while I'm working, and that doesn't bother me. But no, I'm not alone in a room at all. There's a lot of interaction and, you know, second-guessing and conversations with my wife or friends. I didn't want to misrepresent that.

Jenny: I do think there's that feeling that it is just you. That's why if you don't ever have the grandiosity, you're probably not going to manage because it's very easy to go to a bad reading and think, "Why do people even write? Why do people read? Why are we even using these words? They seem very uninteresting." But then you go to a great reading and it feels like magic—how did the person do that?