ARTWRITE #26: SLOW ART

Tadao Ando, Yayoi Kusama, Claude Monet, George Rickey, Hiroshi Sugimoto,

When I went to Japan last month, I secretly hoped I'd learn to eat more slowly. Instead, I learned to look at art more slowly. A few key experiences contributed to this change.

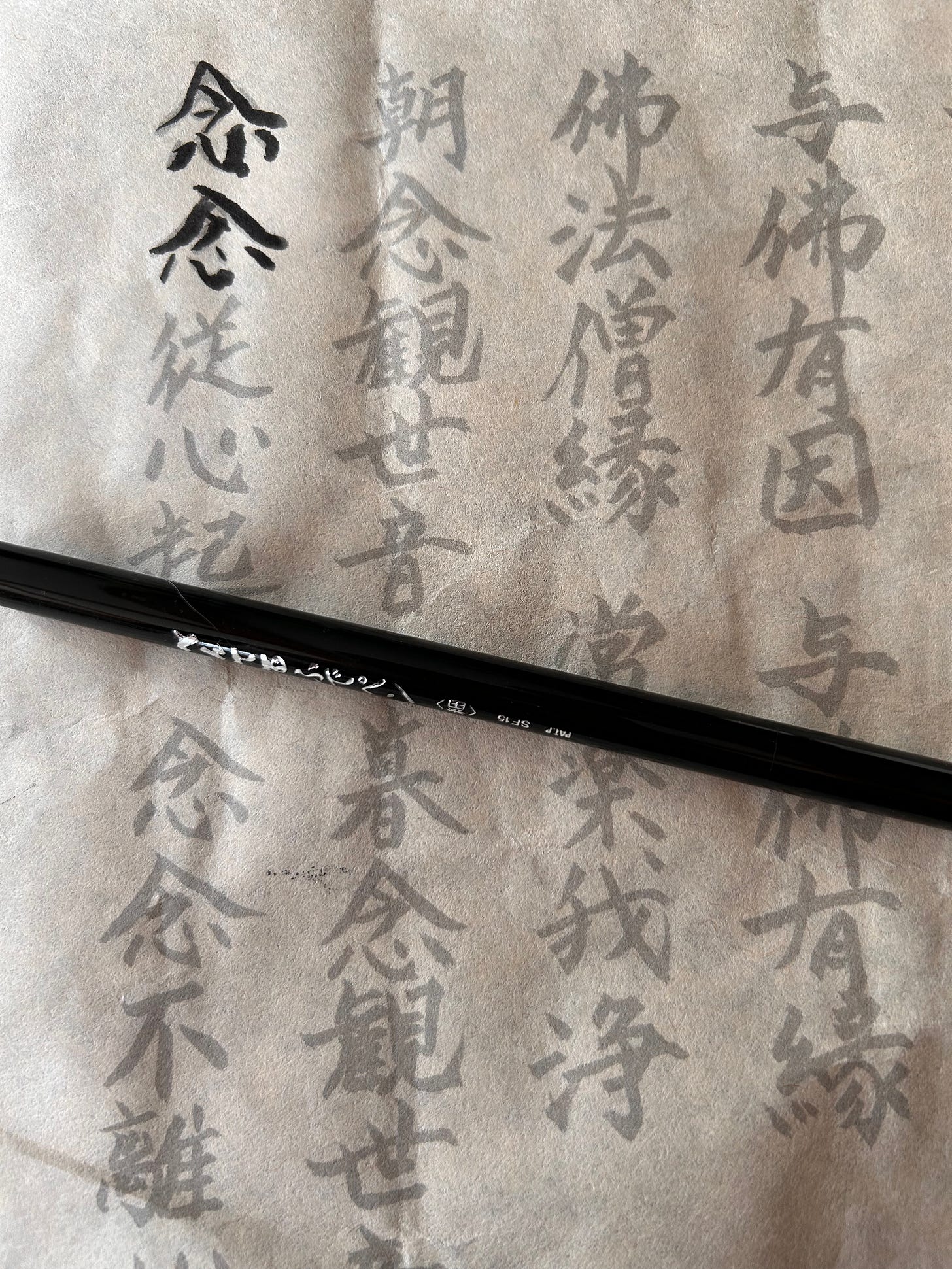

When I arrived at Saihoji, a temple in Kyoto, a monk handed me a sheet with rows of Japanese characters, some tracing paper, and a calligraphy marker, then motioned for me to enter the temple. Rows of tourists sat cross-legged and curved over low tables, fully engaged. Before entering the temple's famous moss garden, we were to copy a sutra to calm our minds.

I experimented with the thick and thin sides of the pen tip, enjoying how the inky black marks made the grey characters disappear. No choices, no imagination, no interior chatter, no generation of ideas, no critical thinking, no emotion, no significance. Each brush stroke was a gesture, and my mind grew uncharacteristically still as I focused on capturing the variety of swooping marks.

Afterward, as I walked the garden, I was mesmerized by a caretaker at work. His broom made light scratching sounds as he gently coaxed scattered pine needles into piles, making sure not to damage the carpet of moss. The task required uncanny attunement and patience. Like Piper in "The White Lotus," who believes that joining a Thai monastery will solve all her problems, I wanted what he had.

Throughout my trip to Japan, I noticed how Buddhist sensibilities imbued every dimension of Japanese life and culture. Whether with objects or rituals, the Japanese value attention to detail, appreciation of process, and noticing the subtle aspects of beauty –natural or manmade. At Takeo Paper Shop, hundreds of paper samples fanned across tables like a flattened rainbow; the owner of Musoshin echoed “Tampopo” in his emphasis on savoring the textures of each ramen component; the bathrobe in my hotel came with instructions for how to tie the sash correctly.

While two weeks in Japan didn’t turn me into a monk, the growing mindfulness I was starting to feel—combined with the heightened awareness that comes from being in a foreign country—primed me for Naoshima, an “art island” in the Seto Inland Sea. Naoshima is home to The Benesse Art Site, a complex of five museums, lodgings, and sculpture park designed by renowned architect Tadao Ando.

I was excited but wary. I love art but typically have a love-hate relationship with museums. Choices, crowds, and a perceived pressure to keep moving overwhelm me. Rows of paintings make me feel like I’m skimming the art from a moving walkway. And most of all, the noise in my head gets even louder: my back hurts; I’m hungry; why are these people talking so loudly?; what’s wrong with me if I don’t like medieval art? In most museums, I confess, I am the opposite of “be here now.”

It was a grey mid-March day when I visited the Benesse Art Site. Fog blurred the horizon line, creating a hazy backdrop for the outdoor sculptures. Yayoi Kusama's bright, squat, polka-dotted Pumpkin stood out against the sea from the top of a hill. Sitting on a concrete slab at the edge of land and water, it beckoned enigmatically. I didn't hurry. I didn't open my phone to google the artist's fascination with pumpkins. I ran my hand over the ridges and valleys, getting lost in the trails of optically illusory dots. I didn't have to understand Pumpkin — being with it, simply noticing, was enough.

I was also drawn to George Rickey's Three Squares Vertical Diagonals. At first, I thought the glittering silver squares of brushed steel, which seemed to balance on corners, were static. Then, their positions appeared to have shifted. Had the wind moved them? The difference was so slight that I wondered if I'd imagined it. I stared at the squares, determined to catch something imperceptible, like seeing your child grow taller before your eyes. Finally, the middle square moved a smidge. I imagine Rickey's kinetic sculpture can put on quite a show on a gusty day. For me, witnessing the infinitesimal was more rewarding.

Nature quieted and framed my outdoor experience, but I didn't expect to discover the same meditative atmosphere in the Ando-designed museums. There's richness in Ando's minimalism. Light comes from unexpected sources (gaps, slits, openings), changing as it interacts with the smooth concrete walls. This interplay brings warmth to Ando's spaces, not the coolness I'd anticipated. His walls rarely display more than one piece, and being able to experience art in isolation was a luxury.

In the Hiroshi Sugimoto Gallery: Time Corridors, Ando also uses glowing white boxes to illuminate dark spaces and accentuate the black-and-white tones of Sugimoto’s photos. The absence of color made me feel like I had stepped into a black-and-white photograph.

I got lost at The Chichu Art Museum but in a good way. I loved moving through the subterranean puzzle of passageways and staircases that wrapped around interior courtyards. Never knowing where I was in relation to the rest of the building amped up my senses. I wouldn’t have felt as present with a floor plan in hand.

Stepping into Chichu’s all-white Claude Monet Space was like entering a temple. Before entering the silent gallery, I walked through a dimly lit passage to a liminal threshold. Shoes were prohibited, and I could feel the tiny marble floor tiles through my socks. With only five people allowed in the room at once, I had time alone with each water lily painting. The soft light emanating from the dropped ceiling and rounded walls gave the room a floaty atmosphere that echoed the paintings. It seemed impossible that I was underground.

Few museums can rival the ones on Naoshima, but you don’t have to go to Japan to learn to see art slowly. Phyl Terry created Slow Art Day, an annual event to teach you how. Phyl understands that taking time with art leads to more discovery and connection. They also believe that slow art negates the need for expertise. That conviction resonates with me as the goal of ArtWrite is to avoid artspeak and make art accessible to anyone.

Slow Art Day just celebrated its 15th anniversary on April 5. I’ll definitely let you know the 2026 date as soon as Phyl announces it.

As for eating more slowly, I’m still working on it.

So much fun to experience the art with you. Magical moments. Dying to go there! Be here now. :))

Wonderful Maggie! You brought me to that extraordinary-sounding place! Thank you!