ARTWRITE #25: VOICE

Elizabeth Alexander, Austin Eddy, Aimee Mandala

Voice is a word that comes up a lot in writing and art. But unlike other creative terms such as composition, theme, or technique, the definition of voice doesn't easily translate from one art form to another. An artist giving a gallery talk doesn't refer to voice in the same way as a student in a fiction writing workshop.

In writing, voice has two meanings. The first is technical and connected to the narrator's point of view. For the past few weeks, I've been wrestling with whose voice should be telling a short story I'm writing. Do I want the narrator in the head of the main character or more distanced and omniscient? This choice will impact how well I deliver on what I'm trying to say in the story. The message, meaning, intention -- all stem from my voice as a writer. That larger concept of voice also pertains to artists.

Voice often gets confused with style, but they're not synonymous. Every art form has a language, and style refers to how that language creates a distinct look or sound. It's fluid (think Picasso's many phases), while voice is constant. Voice is an authentic expression of individual experience and point of view. It's (literally) your breath, a creative inhalation and exhalation. Voice is heady stuff which is why it's so hard to discover. David Sedaris says you have to write "relentlessly" to find it. The same is true for artists.

For this issue, I interviewed three artists who faced internal and external obstacles to find their voice. Elizabeth Alexander struggled with the pressure to stay current. Austin Eddy had to reconcile the burden of his predecessors. Aimee Mandala confronted a radical shift in her approach to drawing.

I had no idea how I wanted to use my voice when I began ArtWrite in July 2020. Now I'm clear about wanting to share my fascination with the creative process by staying clear of pretentious art speak and leveling the playing field for artists.

This is my 25th issue. I hope ArtWrite continues to inspire you.

ELIZABETH ALEXANDER'S voice and aesthetic are rooted and entwined in her working-class background. When the interdisciplinary artist speaks about her process and practice, every aspect (vocabulary, techniques, materials, themes) stems from her heritage and upbringing. Money was tight in Alexander's family when she was growing up. Her parents married young, and her father began welding at 15 and left high school to help support his family.

Alexander's parents made, refurbished, and traded objects with family and friends. Her father made steel furniture; her mother turned old bookshelves into a dollhouse and sewed clothes. The artist traces her attraction to "really intense florals" to the curtains her mom made, the popularity of Laura Ashley in the 90s, and the fact that her British grandmother's influenced her mother's taste.

Her parents' resourcefulness taught Alexander to see the possibility in found objects and influenced how she works with common household items. "Once a youthful exercise in curiosity, I find catharsis in purposeful acts of deconstruction and revitalization of these found materials."

Growing up, Alexander was aware of her family's longing for status symbols in the home. "I cannot tell you how many times I heard my dad and his family talking about how they would buy nice things when they got their break and didn't have to work so hard." Alexander draws on these memories in her work. Her installations explore how American culture stokes desire in the working class to maintain appearances and acquire objects and upward mobility.

The notion of objects of desire took on another meaning when Alexander visited her father's welding shop, where she was the only woman in a male-dominated environment. That tension persisted when she got a job fabricating steel railings. Men in the shop and on construction sites expected less of Alexander because she was a woman. Just trying to find protective gear to fit her hands or body reinforced Alexander's alien status.

In the series "Welder's Daughter: Safe and Powerless," Alexander plays with gender and class by transforming utilitarian objects such as masks, tools, and protective clothing into precious objects. To create the intricate lacework in the piece below, Alexander laser cut patterns from steel railings into her welding jacket and bib.

As a young artist, Alexander never questioned her voice. Her high school art teacher referred to her as a creative machine. "I kind of just work and work and work and work and process as I'm working."

When Alexander went to art school, she hoped to refine the visual language that had come so naturally to her. Instead, the young artist struggled to find support for her work.

Despite the 1970’s Pattern & Decoration movement, decorative was still a dirty word in 2000. The art establishment derided ornamentation or anything related to domesticity. As her peers strived to make clean objects inspired by reductive minimalists like Martin Puryear, Alexander was "doing floral explosions."

While Alexander had some supportive teachers, the loudest voices were discouraging. Teachers urged students to take themselves out of their work if they wanted the art world to take them seriously. Given that Alexander ‘s art was steeped in personal experience, she lost confidence in her ability to discuss it. "When you're making work that has so many ties to your own story, and people are telling you to take yourself out of the work, it makes it really hard to talk about it."

Reading about writing helped Alexander to claim the full expression of her voice. Books like Ann Lamott's Bird by Bird changed how she thought about her work. "It told me my story is important. People do care."

And here's the best part: Alexander also discovered the power of stories to speak to others. "The more I tell my own story, the more success I've found in terms of people responding positively to my work, wanting to talk to me about it, wanting to show it.”

It took several years for Austin Eddy to find his voice as a painter. Part of his struggle was his awareness of the artists who came before him. " History is one of those inescapable things. You are always crashing into your predecessors." Eddy had to find a way to navigate the presence of the past, but he was also interested in picking up where others had left off. "The challenge was to find a way to say something without mining too much or taking too little."

While Eddy was at The School of The Art Institute of Chicago, he reached a point where he felt "bogged down" by narrative figuration. Determined to shed the skin of representation, he moved into a form of language-based hieroglyphic abstraction. "I needed to cut everything out in order to find a way to speak a story without telling the viewer everything." Omitting the figure forced Eddy to rely on tone, color, and the relationship of shapes to express himself.

During this transition from hieroglyphic paintings, a central form divided time and place in Eddy's canvases. That form slowly transformed into a boat-like structure that resembled an individual sitting on the back of a bird. Eventually, only the bird remained.

By 2018, Eddy had honed a language of his own, a hyper-flattened style that lies somewhere between figuration and abstraction in which he reduces the birds' essential features to playful shapes and colors.

Birds per se don't interest Eddy. Instead, they are functional, providing a place to hang narratives rooted in semi-autobiographical experiences. Eddy describes his birds as "a conduit for understanding the human condition" and a "metaphor for the burden of existence."

Even though Eddy gravitated to abstraction, his work remains personal. For instance, a recent series about grief alluded to the cycle of nature and how it brings things into existence and reclaims them when they reenter the earth.

Eddy likens trying to find his voice to working in a swamp; ideas often become muddy or muddled. "You think you're on a clear path. Inevitably something will change, and you have to renegotiate your understanding. You may reach a point when the work doesn't make sense or feels unsatisfying because there is never a right answer."

It took Eddy multiple iterations of painting to find a way to visually express what he was seeing and to learn how to articulate it. While he admits that this experience was frustrating, he also considers it the most rewarding part of the creative process.

Aimee Mandala grew up believing she lacked the drawing skills that her siblings had inherited from four generations of architects. She never imagined becoming an artist. Although she did end up in architecture, it was at the business end of the field.

After college, Mandala tried a painting class with her father and sister but gave up because she couldn't produce what she saw in her mind. Ten years and two kids later, the images on a welder's Instagram page sparked her desire to try art again.

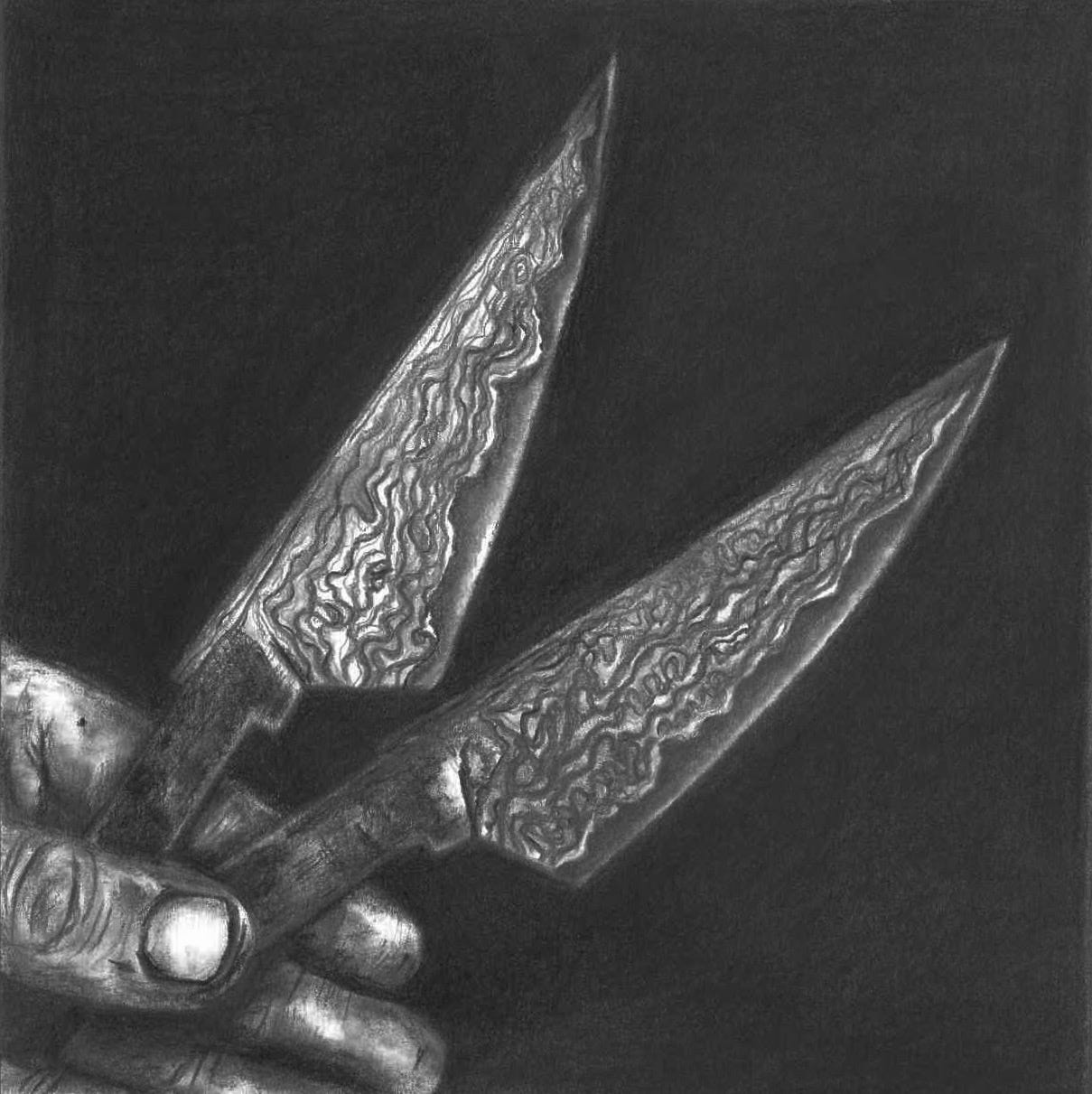

Inspired by the passion that the welder put into his work, Mandala felt compelled to draw his hands. "They were just covered in metal dust, blackened by it. And you could really see the intricacies. I just thought it was so beautiful." After laboring over the drawing and sending photos with questions to her father and sister, Mandala was surprised to find that it wasn’t horrible.

Compelled by the grittiness and texture of hands, tools, and workwear, Mandala became an accomplished draftsperson, achieving recognition for meticulous drawings that celebrated the creative process of craftspeople. "So often, as a society, we're so focused on the end result of a product or thing that we're not thinking about all the heart and hard work and dedication that's put into making that thing come to fruition."

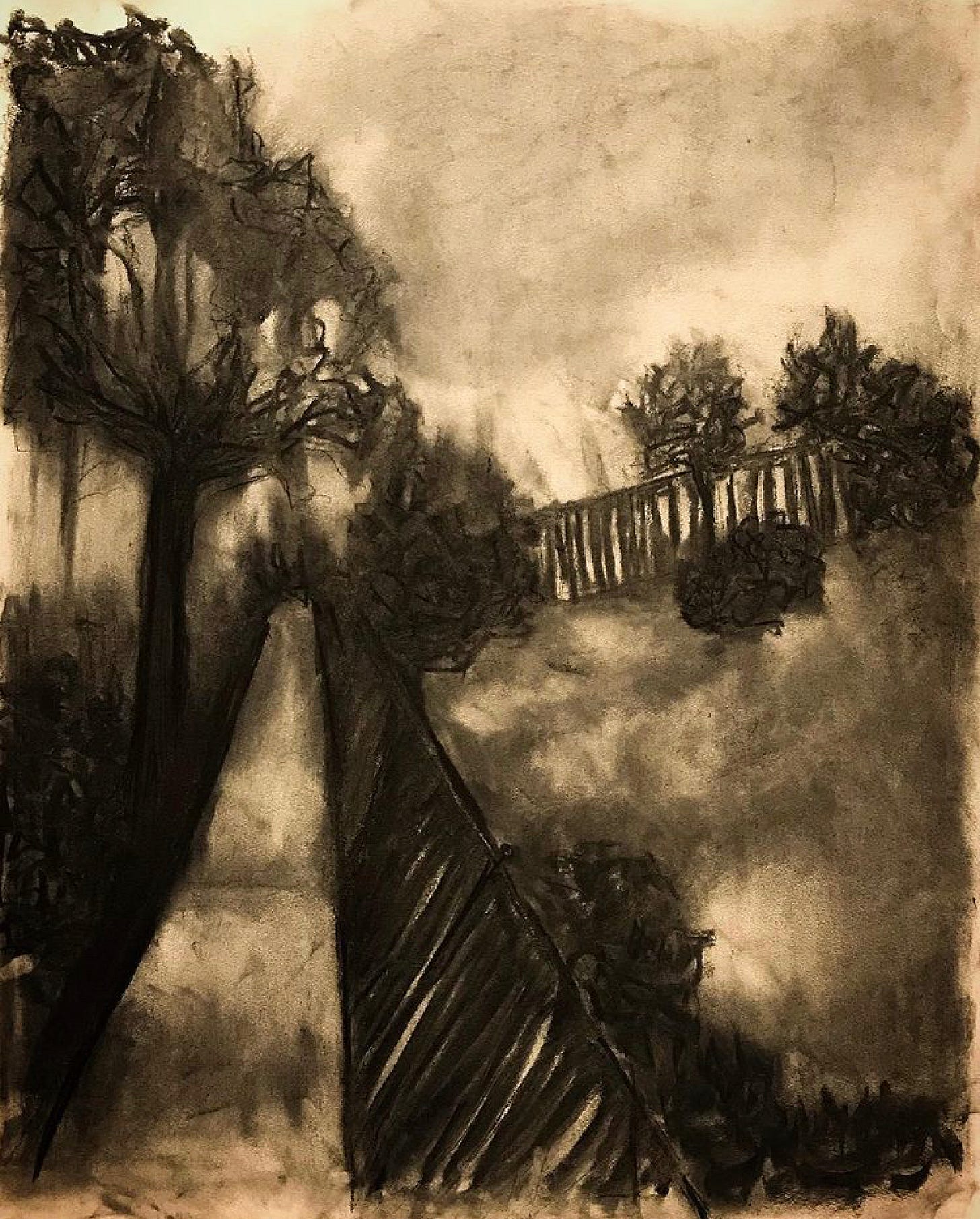

Early last year, a twilight walk changed the direction of Mandala's work. As a woman, she was reluctant to walk alone at night. But an inner voice convinced her to push past her doubts, to take the risk. While she walked, Mandala felt a strong sense of liberation and snapped a photo to capture the moment.

Even though the image was fuzzy, Mandala immediately wanted to paint it. Because she wasn’t used to working freehand without rulers and measurement guidelines, Mandala drew a study, smudging the charcoal with her fingers to blur the image. The result looked nothing like her usual precise replications. Evening Stroll was looser. Moodier.

Until this point, Mandala's practice had been straightforward. Technical drawing had given her a foundation. It taught her to structure a drawing with thoughtful composition, value, and proportions. She knew what steps to take to replicate a boot or a blade and found comfort in following them. "It's a process to get to the end. And then, in the end, there's a clear result. I know I'm done with a piece because I see it. And it's what it should be."

At first, the looser approach to drawing made Mandala feel vulnerable. People who knew and liked her work had a defined set of expectations. But her voice was too loud to ignore.

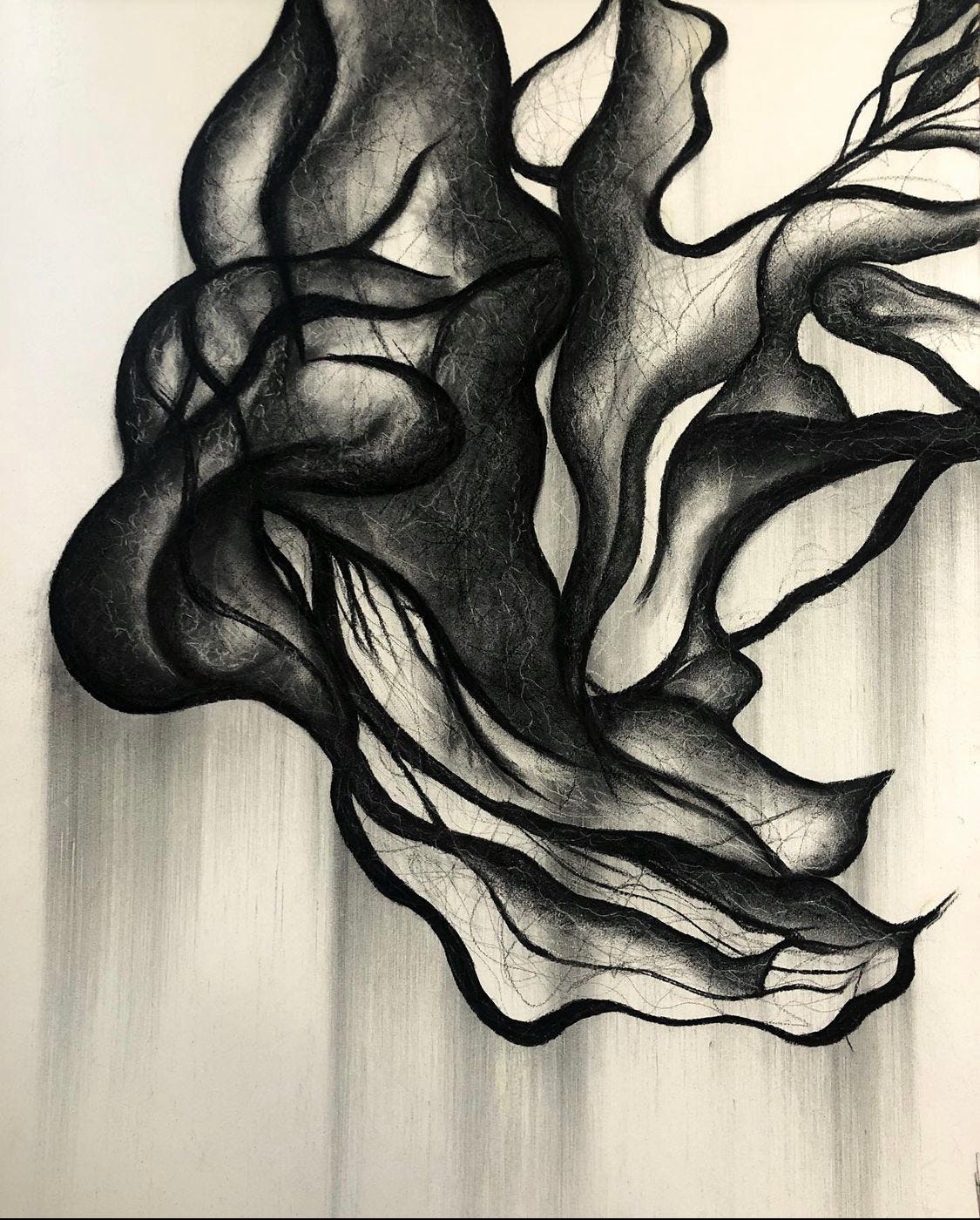

Mandala began using her skills to be more expressive, relishing the chance to tap into a different part of her brain. She finds not knowing when she's done or if she's moving in the right direction to be thrilling and frustrating. "You go through the process, and you're thinking: oh, it's going to look like this. And then it doesn't look like that. And so you take a different direction and find that that doesn't work either. But then, all of a sudden, something clicks. It turns into something else that works. It's a push and pull."

Mandala is currently moving back and forth between styles, looking for a way to meld the two. "Internally, it's me finding my voice. It's me trying new things and trying to reach outside of my comfort zone because that's when you grow."

I enjoyed this, thank you for your writing, it is clear and insightful.

Loved this. Will share it with my grad seminar!