ARTWRITE #24: NOT KNOWING

Leslie Alfin, Daniel Gerwin, Manuela Gonzalez, Robert Hooper, Joyce Kozloff, Sonya Sklaroff, Liz Titone, Maximilian Welz

The hardest part of writing for me is not knowing. Not knowing where it's going. Not knowing if it's good. Not knowing if I should abandon something or stick with it.

The discomfort of not knowing is invisible and insidious. It doesn't wrench my stomach or make my head pound; it simply makes me not want to write. Here’s how the late David Rakoff described it: “Writing is like pulling teeth. From your dick.”

Rakoff’s take explains why I've spent the last three months ironing the flange on my pillowcases, charting the ratios of ingredients in different galette dough recipes, and using my husband's hair clipper to depill sweaters that I don't even wear because I live in LA.

I hit bottom as the pressure to make New Year's resolutions loomed. I had to find a way to dig myself out. It had been months since I'd done an ArtWrite, so I decided to build an issue around one question. It would be easier to edit than my usual multi-interview format, and I'd get some much-needed inspiration.

This is the question I posed: When an idea isn't working, how do you know if you should let it go or push forward? And this is my takeaway from the eight artists who responded: unresolved ideas are opportunities, not doors to slam. They may be put aside to simmer, but they're never completely discarded. Ideas get repurposed and reimagined, generating new ideas that may or may not bear traces of their origins.

Jami Attenberg explains why it’s no different for writers in her most recent Craft Talk: "No matter what I'm writing, it's never a waste of time. I'm always working through something. I'm always trying to arrive at a new location. Even if I can't see it right away, it's happening beneath the surface."

I knew all this but had stopped trusting the creative process. I’d lost so much momentum that I forgot what happens when I write: how words, images, and associations trickle, sometimes even flow, from out of nowhere. Except they don’t emerge from the ether. They come from me. And they always will as long as I continue to sit with the discomfort of not knowing where they’ll take me.

I can't point to one incident when I've completely abandoned a direction, idea, or technique. In some way, each element, no matter how small, troublesome, or uncomfortable, contributes to what comes next.

Eventually, the work itself begins to talk back, to let me know what it needs. And it is not always a polite discussion.

For me, the best directions often emerge from a robust argument. And even though the struggle is frustrating, it is also when I learn the most. Out of my comfort zone is when I begin to listen and allow the work to call most of the shots.

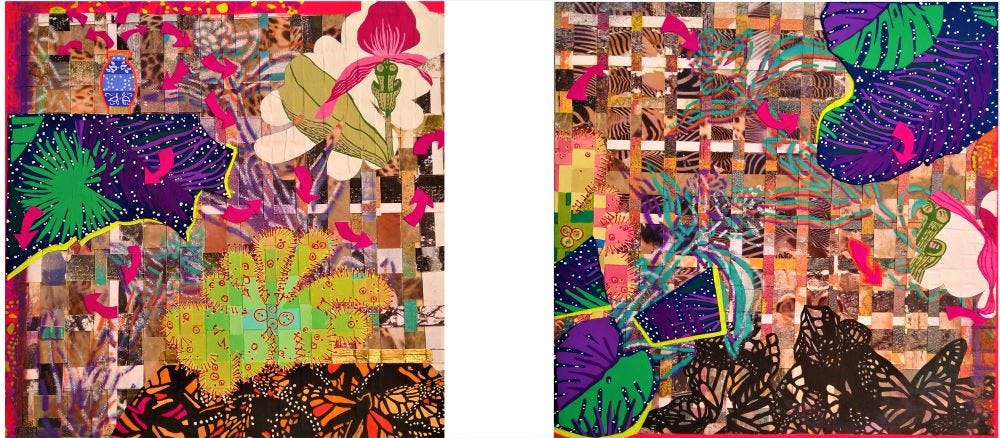

My recent Chaos Quilts demonstrate how conversing with the work is the heartbeat of my practice. There is a steady evolution from the representation of space, depth, and the illusion of a kind of peripatetic aimlessness that initially occurs via a 2D painting on a singular flat surface. As the series progresses, each new piece includes integrating, first minimal and later increasing, 3D elements and multiple panels, eventually straddling the lines between painting and sculpture. Achieving Zero Gravity, a work in progress, indicates a clear direction for what is to come.

One of the many reasons I paint on wood is that when an idea isn’t working, I am able to let it go and push it forward at the same time. When I get stuck on a painting and simply cannot see a solution, I cut the work up into several pieces, which then get reassembled into a brand-new whole, or else find their way into other works-in-progress down the line.

Long Day Bleeds Into Night (2021) is a perfect example: it was originally a solid circular(ish) shape, but when I couldn’t breathe life into the painting, I cut it into quarters, rearranged the quadrants into new positions, and opened up an aperture in the center: suddenly new pathways appeared. I was then able to complete the work, and the resulting discontinuity between each of the four sections is integral to the experience of this painting.

Awake In The Dark (2021) never changed its shape but was heavily repainted, which is not at all unusual for me. My process requires as much destruction as creation along the way to a finished painting. Although some things progress smoothly and seem to be making themselves, I am not the kind of artist who plans a painting in advance and then executes it. For me, it is always a process of groping in the dark and gradually discovering how the idea in my head will find meaningful form as an object in the world.

My decision-making process is intuitive. If I had to describe how to know if I should let an idea go or push forward, I would say I base the decision on the relationship I have with the idea or with the piece itself.

I often make the best work after being forced to pivot, layer, and rework a painting, but when the effort feels more draining and demoralizing than productive, that's when I tend to stop and put the work aside. I will decide later if it's completely done. Ultimately for me, it's about finding the right balance between discipline and ease.

I made these collages by cutting up pieces of a painting I'd tried to rework for months. Before letting it go, I rearranged the composition at least five times, altering the color and playing with the patterns. I probably made ten different versions only to end up frustrated and exhausted.

Reworking the painting into collages ended up being a good choice because I learned a lot about my process and compositional limitations. The series expanded my vocabulary and made me excited to move forward without dwelling on the frustration I'd had while making the painting.

Only once in another place and time, I was so distraught with a painting that I hurled a shop broom at it, butt end first - it bounced off the canvas, which was unscathed; however, the sheetrock wall behind it was left with a gaping hole—my penance.

Otherwise, I typically feel a painting unresolved is simply an opportunity that I am not (yet) big enough to see. Paintings, like dreams, are often instructional and compensatory. They are always (hopefully) at least a few paces ahead.

John Peck’s “March Elegies” includes a narrative of Oskar Kokoschka gathering objects for a painting. Like a cow to a salt lick, I frequently return to this portion of the poem and encourage my students to read it because it captures how being open and receptive to intuition’s “obscure sign,” more so than to logic and reason, is often a harbinger of an image’s resolution:

Believable illusion, as mist Before whatever unshifting stone. But mist itself plays the revealer, Condensing each outline, And I cannot will that disclosure. Circling, a man may retell the story Lived by another because neither Is in that way free. Kokoschka had set a fresh portrait In his host’s boxroom to dry. The host Had brought home the Easter lamb, and asked him To remain as a guest, He could stay the weekend. And the painter, Looking at the dead eyes of that lamb, Proposed suddenly to take the skinned Thing to the boxroom And do it. If he began soon, there Would be time enough before Sunday. This man given often to foresight For once in no way Summoned that penetration (the war Not far off and the wound it offered). He found what he needed: a tortoise And light-shy lizard, A tame white mouse and an old oil jar. But still missing was some final touch For the composition; as he poked Through the great house, each Thing took light from his desire and flared Or failed to crystallize the ransacked Compilation. At last on the maid’s Windowsill, erect In the pale phosphor of its full bloom, One hyacinth. Although its odor Was a dead child’s whom he had painted dead, That did not matter, It gave scale, focus, the obscure sign, In the way a story, overheard, comes In upon life at hand and one says, ‘That is how it seems. . . . ’

I can't let go of ideas, even if they aren't working. My impulse, almost always, is to keep gnawing at it, trying to get it to perform for me. After completing a body of work, I need to reinvent myself, re-energize myself, get excited again. Sometimes it takes a while. Exploring a new media or process has often helped.

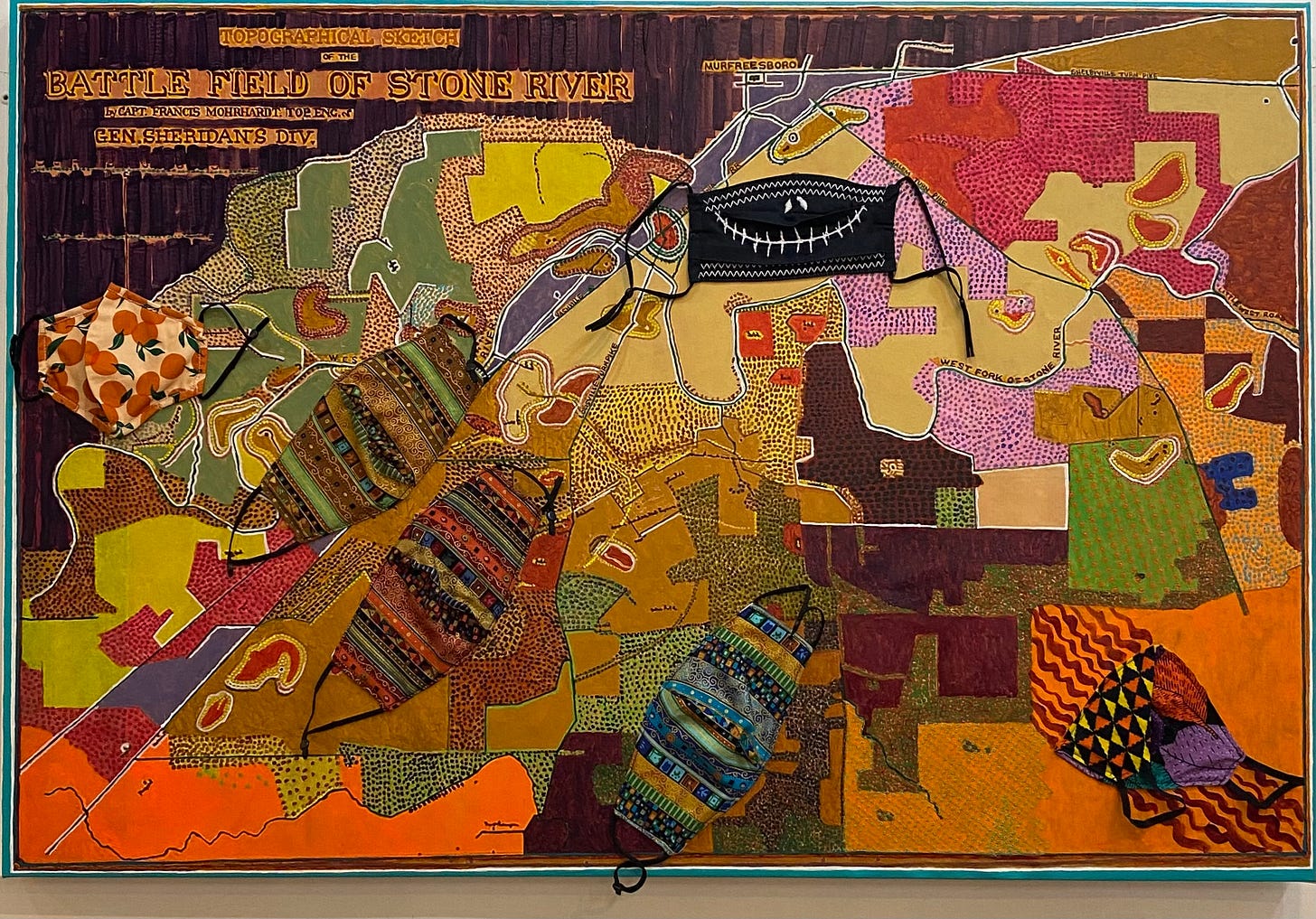

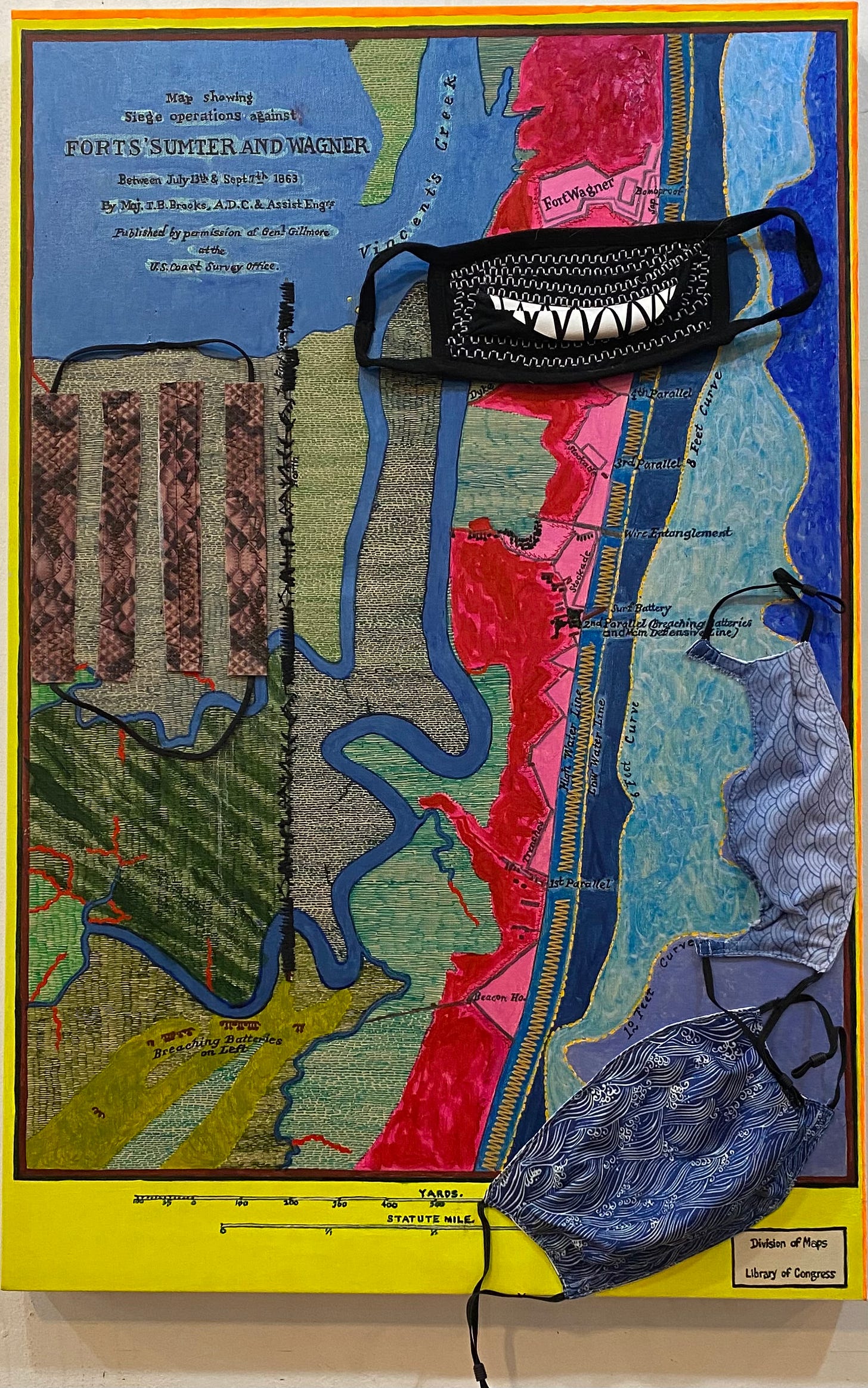

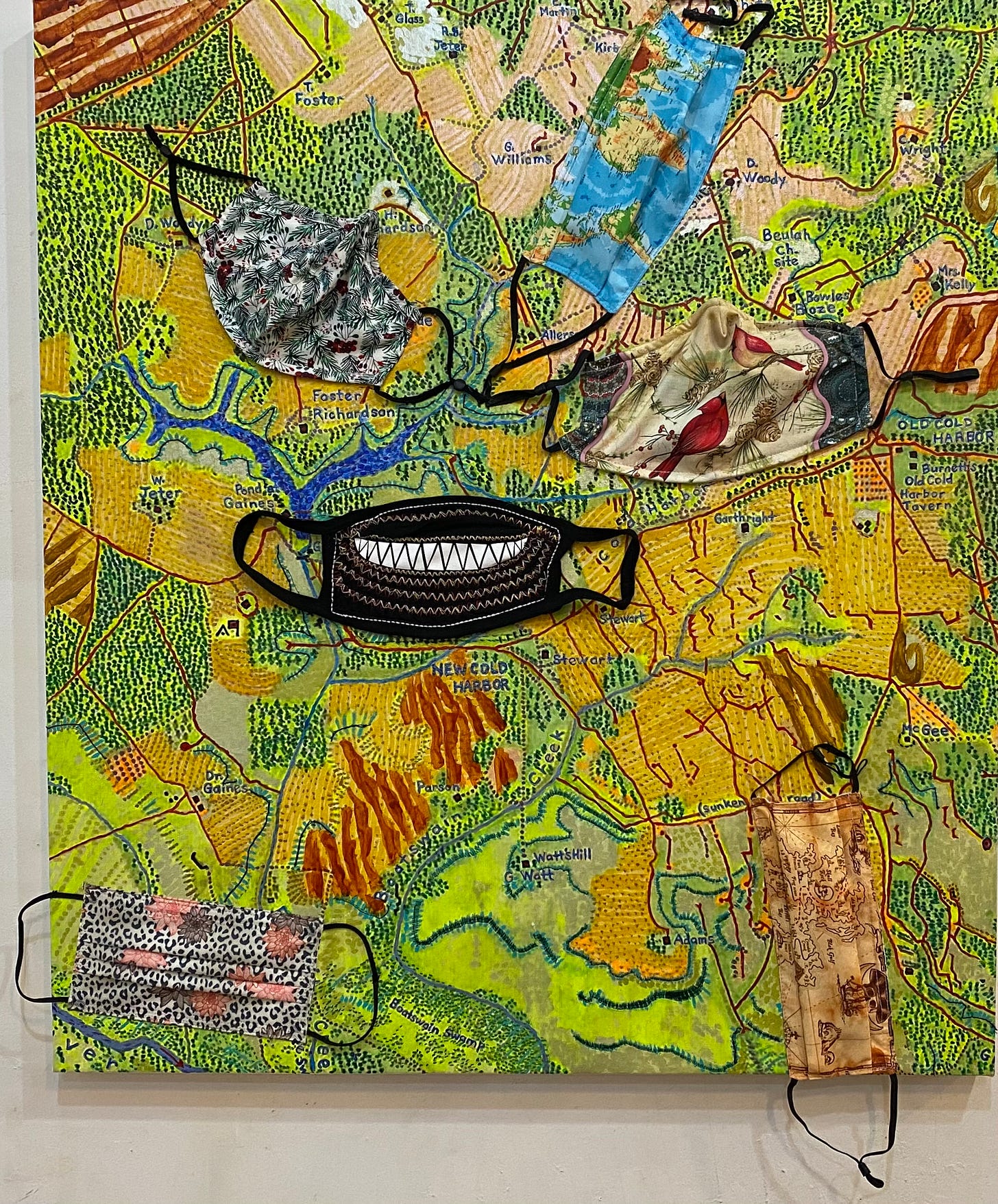

I've been painting Civil War battle maps for close to two years. I layered viral outbreaks over the first series. I thought it was a dumb, obvious idea, but I couldn't get it out of my head, and nothing else felt as compelling. Sometimes what makes an idea work is simply the execution and sheer will.

I'm now starting over again, trying to build on that series, but without the viruses. I'm attaching masks to different Civil War battle maps, bandaging them over the painted surfaces.

I ask myself whether it's another stupid, literal idea. My friend, Judith Solodkin, master printer and founder of Solo Impression, is sewing them on with her digital embroidery machine. This is something I've wanted to explore for a long time, but I didn't have the right project. Now I do, and I'm getting excited about it!

Two people, whom I trust to tell me the truth, don’t like the masks - so maybe it’s a mistake, I’m not clear yet. Of course, my perverse reaction is to just add MORE!

I love to paint portraits. Individuals will sit in my studio and chat with me and hang out, or sometimes if they are musicians, they play an instrument. As I paint my visitors, we get to know each other.

This is the first portrait I completed of Bobby Wooten III. I did it in my studio as he played his guitar. I found it easy to record Bobby's likeness but was so involved in depicting his features and mannerisms that I failed to capture his essence. I also struggled with getting the background to capture the flow of the music Bobby was playing. In the end, it was still too stiff.

When Bobby left, I began a new painting to address the unresolved aspects of the first one. I wanted the background to reflect the music that he was playing, so it became more wavy and fluid. Working from my imagination and memory, I also focused more on Bobby's demeanor and temperament. The new portrait captures his love for his guitar and music. It's a study of how he felt and how my feelings of gratitude and admiration for him.

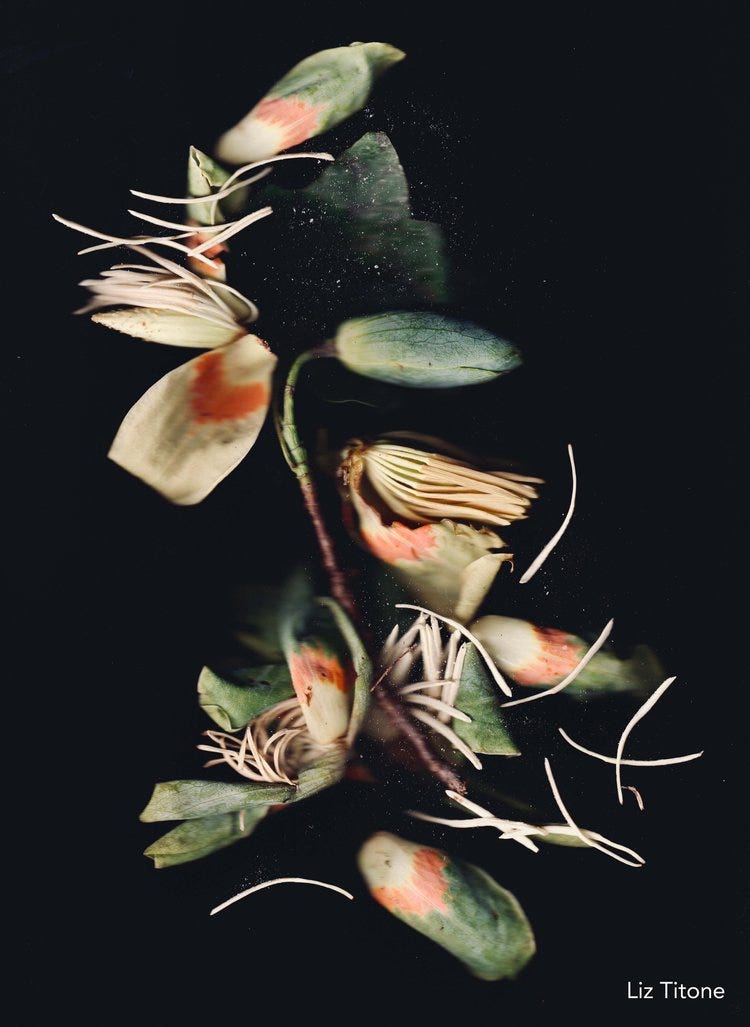

The pandemic forced me to reconsider how I make photographs. Roaming around with my camera was no longer an option, so I began scanning natural objects. I had to develop a new set of skills to accommodate the process of composing an image on a scanner. Everything I put on the glass appears in reverse once the scanning mechanism has done its magic. I promptly discovered that I do not possess great stores of patience. At times, I felt so out of my comfort zone that I seriously considered picking up the materials, scanner and all, and tossing them out of the window! Trial and error led me to a place of relative ease, but sometimes I just throw my hands up in mock surrender.

I gather my materials in forests and on beaches. Low and behold, these bits of nature travel with hitchhikers. At the scanner, my carefully crafted compositions reveal evidence of their origin: soil or sand nestled between petals or *gasp* in front of leaves! The occasional insect. Oh! The mess!

I had to pull back, resist the urge to clean the "offending" material and remember that I’ve taken everything from its mother source. I am a visitor. I may even be a trespasser.

Moving through this process has forced me to accept what I cannot control. I have come to think of it as a parallel to the pandemic. And, at the end of the day, I have documented the experience of letting go, the experience of pushing forward, and the experience of sitting back and seeing the beauty in it all.

When an idea turns out to be a failure, that’s often a good sign. Failure lets me get a better understanding of what I want to achieve by allowing me to confront imprecise and unconscious expectations I previously might not have been aware of.

Often it’s quite easy to spot something that is not working but trying to fix it forces me to re-evaluate what I have done so far and come up with innovations, to be creative. That was the case with Frenchultramarine #8 because I don't typically do paintings of that size.

In my eyes, making art is a process of identifying problems and coming up with solutions.

It's reassuring to see how common these struggles are...I'm reminded of when I was dating a real asshole in HS and my mother told me it was good to know now what I didn't want. I think the pandemic is making starting new things even harder, at least for me. I do see it's making others choose new materials, or smaller scale, and that is putting them in that experimental mind set. Another enjoyable newsletter.

As I sit here getting ready to go to an interval training class at my gym (for the first time in months/years??) I thought of something a trainer said to me me once, “the exercise you are having the most difficulty with is the the thing you need to work out the most.”