September 25, 2021

As far as I know, my father didn't aspire to write the next great American novel. He wanted to be a comedy writer.

After graduating from Syracuse University, my dad moved to New York City and began writing with Dee Caruso, a college friend. Within a few years, their work appeared in MAD and SICK magazines, and stand-up comedians like Don Adams were performing and recording their material.

The late 1950s was the heyday of New York's nightclub and cabaret scene. At Upstairs at the Downstairs, Julius Monk presented a series of satirical revues, many of which featured sketches by Dee Caruso and Bill Levine. As a kid, I used to get a rush of pride seeing my father’s name on the back of the cast recordings.

During the years he partnered with Dee, my father had a day job in advertising. He'd married in 1957 and had a daughter to support. I arrived in 1964. Three years later, he opened an eponymous corporate communications shop.

In the early 60s, Dee moved to LA, where he became a head writer for The Monkees and Get Smart. When I was around 5, my father went to California to give writing for TV a shot.

The story goes that my mom gave him six weeks. When he got home and said we weren't moving to California, I thought it was because he'd been terrified during the earthquake he'd experienced. (I loved telling my friends that he ran out of his hotel room in nothing but his bathrobe).

A few years ago, a family friend filled in the gaps: while in LA, my dad pitched a script about a Black president. Dee said no one would make it but went with my dad to take meetings with producers. Each one rejected it—too controversial. Defeated, my father came back to New York and put all his creative energy into his business.

All young people have dreams about who they want to become. Some cling to those early dreams, but usually, circumstances force people down new paths.

Those turns and how creative people respond to them interest me. That's what this issue of ArtWrite is about, and the whole time I wrote it, I kept coming back to my dad's story. I'm now more impressed by how he re-channeled his creativity than I was by his name on album jackets.

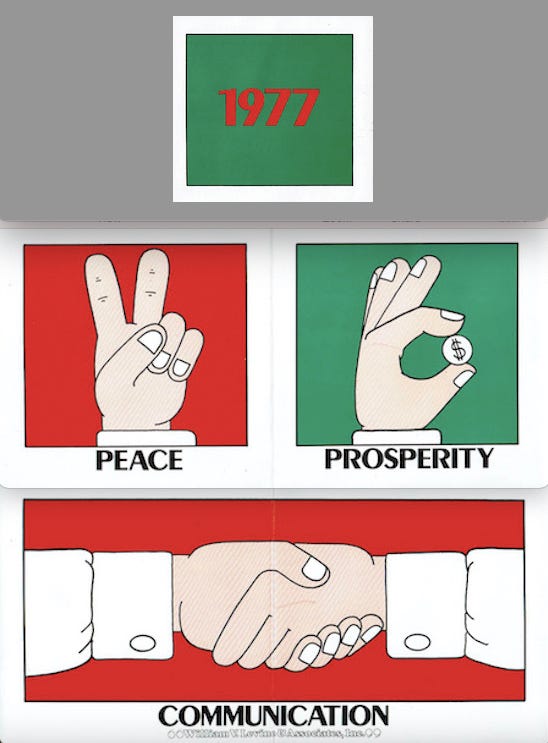

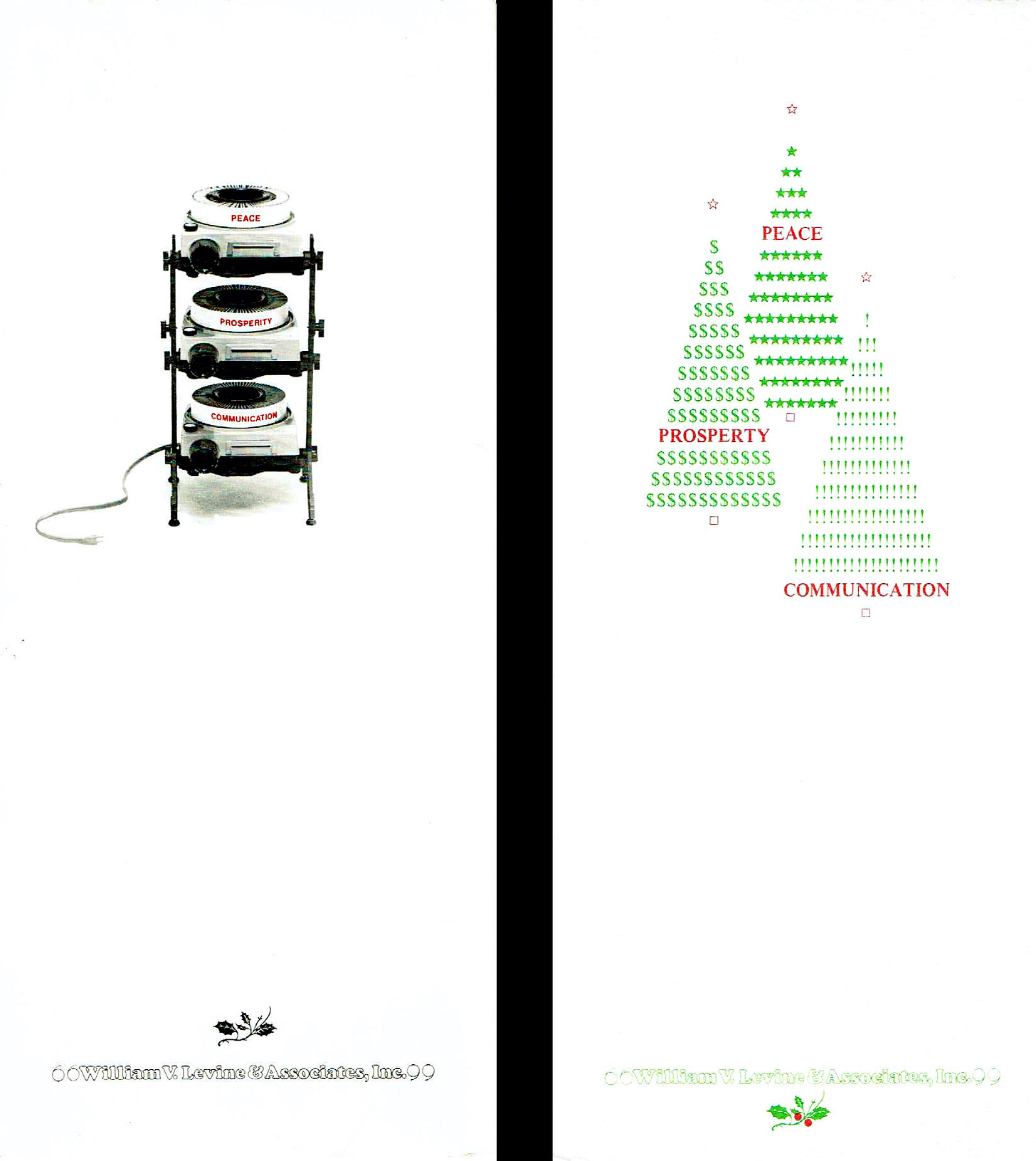

My father approached each sales presentation or promotional brochure as an opportunity to push himself. No one would have known if he pitched an old idea to a new client, but he refused to be a hack. Even his company Christmas card was a self-imposed creative challenge. Every time the holidays approached, he'd fret about coming up with a new take for the annual three-word greeting.

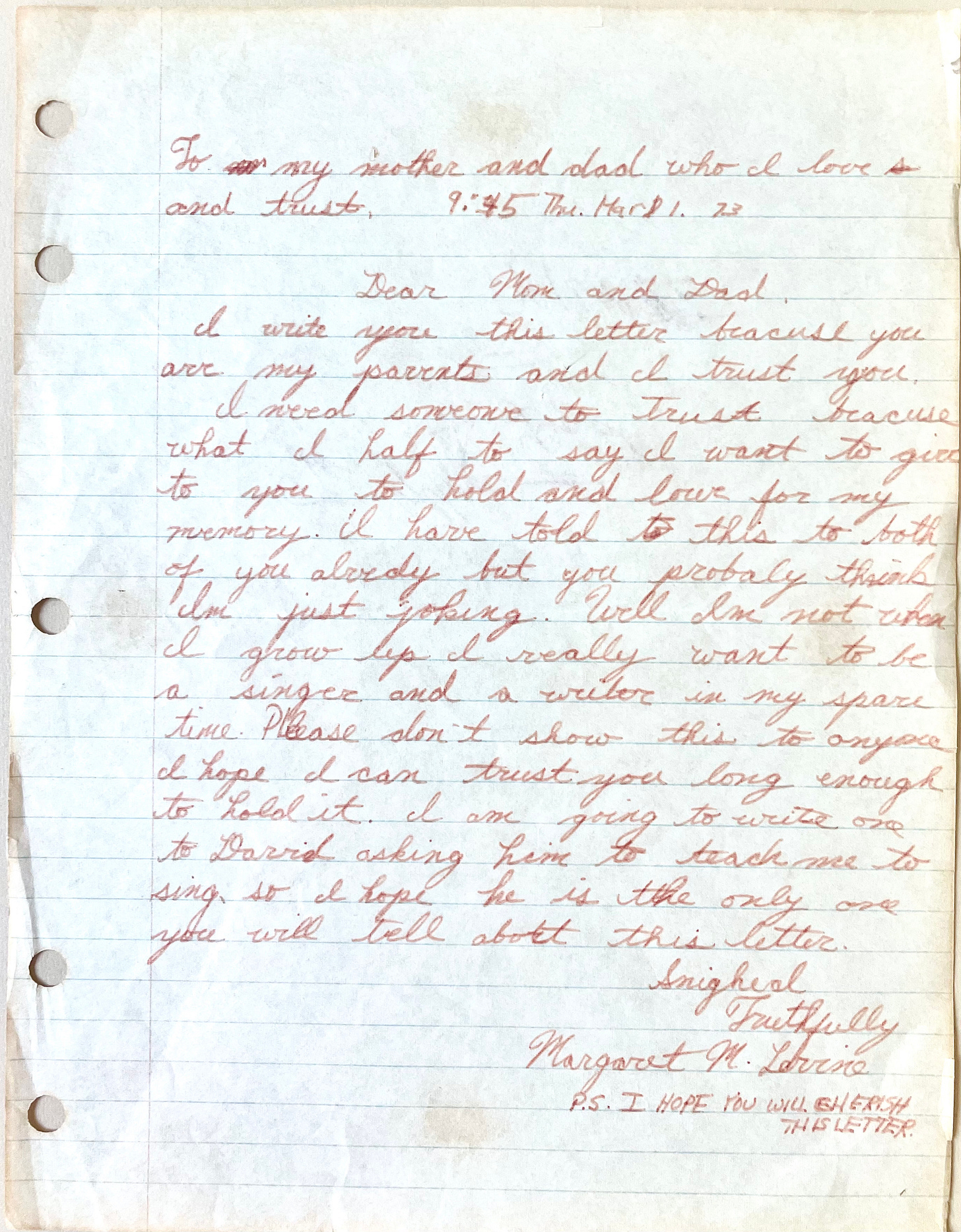

Like my father, the artists in this issue also drifted or deviated from their early aspirations then discovered new ways to be creative. That's my story, too. I was 9 when I confessed my desire to become a singer and a writer in my spare time. Twenty-eight years after getting my MFA, I finally returned to writing a few years ago.

I recently read an interview with Ruth Ozeki, who said the best writing advice she ever received was "the writer you are is enough." That's my new mantra. ArtWrite may not have 10 million followers, or even ten thousand. I may never publish a novel. But the writing I'm doing feels good and right. That wouldn't have been enough for me when I was in grad school. But it is now.

________________________________________________________________________

Stephen Lewis's ambitions to be a photographer began to form as a fine arts student in college when he became "spellbound by visions of art, traveling the world, and hanging out with fascinating people." The summer after his junior year, he went to New York, found work at a gallery, and set himself up to return after graduation. "My fantasy went something like this: I would start in downtown Manhattan, get some gallery shows, and eventually land a one-person show at MOMA, then a monograph or two."

For a class assignment, Lewis took a portrait of a woman with her eyes shaded. He liked it, but the teacher took off points, insisting that you have to see the subject's eyes in portraits. In a cheeky response, Lewis made a series of portraits with cropped-out eyes. That series ultimately landed him a job as Annie Leibovitz's second assistant in 1986.

Lewis knew nothing about commercial photography. Working for Leibovitz and then other photographers exposed him to the pros and cons of the industry. The artist in Lewis wanted to pursue his art, but he was also attracted to making good money, working with the best magazines, and travel. He found role models who shot high-level commercial work and also showed in galleries, and that balance became his goal.

By 1993, Lewis had opened a studio. Known for his immaculate still-life photographs, he became busy shooting editorial assignments for magazines and creating advertising campaigns for luxury brands like Hermès and Louis Vuitton.

Striking the balance Lewis had hoped to achieve was difficult. When he hit his 40s, Lewis felt burned out and creatively dissatisfied. "I had a chip on my shoulder about being a commercial photographer and spent a lot of time and energy doubting my career."

Photography had lost its element of surprise. "When you're developing pictures in the tray or doing a shot with splashes or smoke or action, you never know what's going to happen." But in advertising, there's little room for this type of spontaneity. For example: the products below appear to stretch the stocking and spill from the capsule, but they were actually "rigged within an inch of their life."

Lewis also found it challenging to express his voice in commercial work. The realization hit 15 years ago when he shot a story about foods injected with nutrients extracted from other sources. As Lewis and his assistants created a kind of Arcimboldo still life out of Cheetos and other foods, anything they didn't use went on a plate on the side of the set. When Lewis saw the reject plate, something hit him. He made some minor tweaks and shot the image at the top of this issue.

"George Saunders says your voice consists of moments when you're certain, and that's who you are. It's a funny thing to say, but I was certain it was good." Lewis loved how the image seemed to "reverberate in this weird space between good taste, bad taste, elegant, and bizarre, without really committing." It was him: classic (it seemed to allude to a Dutch still life) but irreverent. Although the client ultimately went with a less restrained selection that provided "a quicker read," Lewis was so pleased with his image that he didn't mind.

Determined to reconcile his creativity with his commercial career, Lewis read countless books on photography, creative self-help, the artistic process, and novels about characters in a similar predicament. He also worked extremely hard in psychoanalysis.

"The path to reconciliation had to do with recognizing my talents and limitations, then separating them from a persistent set of thoughts that had created a fictional version of who I believed I should be.” That meant Lewis had to acknowledge how he isn't comfortable being left to his own devices or following a path without knowing where it leads. Once he had that awareness, he could accept that he likes being told what to do and recognize how strict parameters play to his strengths.

For a Marie Claire assignment, Lewis had to make the images graphic and readable but do it in a way that no one had ever done before. "Shooting transparent objects is always a nightmare. It takes some technical skill to depict a clear plastic shoe on a white background without turning it into mush." Lewis solved the problem by adding color to animate the flat subject matter.

To attend to his creative spark, Lewis started playing with new techniques and shooting for magazines with smaller budgets, allowing him the freedom to experiment.

The idea for Shroud came to him from a passage in WG Sebald's The Rings of Saturn, in which the narrator describes the practice of covering anything that a departing spirit might struggle to leave behind.

Ironically, personal projects like these have led to more work. Livraison, an arts magazine, asked Lewis to do a portrait series after seeing Shroud in his portfolio, then Newsweek used one of those images for a cover story.

Independent work has also helped Lewis to develop his voice with more clarity and confidence. There's nothing as satisfying as feeling like I have communicated some part of me." At the same time, he's wary of spending too much time thinking about his voice. "It's more important to produce work and enjoy the process. Through that, my voice will develop."

Whatever conflicts Lewis had with commercial work are now behind him. "I think the way to describe where I am right now is I try to create with a disciplined chaos. Flaubert has a quote: 'Be regular and orderly in your life, so that you may be violent and original in your work.' I think of that often."

________________________________________________________________________

The first chapter of Michael DeJong's story is similar to Lewis's. Determined to become an artist and see his work on the walls of galleries and museums, he spent the bulk of his grad school loan traveling from Illinois to New York to see art and drop off slides at Soho galleries.

As DeJong neared the end of his graduate studies in 1988, a midwest curator purchased his entire thesis show of three-dimensional collaged constructions. The young artist promptly moved to New York and began realizing his dreams. Within a few months, he was in a group show and had his first solo show soon after.

In the late 1980s, Dejong's mother and stepfather died in a car crash while looking for wooded land on which to build a home. Decades before, after World War II, his biological parents had immigrated from the Netherlands, hoping for a piece of the American dream.

Dejong interpreted that dream as land and began to paint landscapes, some no bigger than a quarter, using 000 sable brushes from which he'd cut off most of the bristles. These "meditative vehicles for memory" honored his parents' dreams and provided a place for them to rest.

"Borrowed Paradise," a later series of tiny watercolor landscapes on large pieces of paper, was also a success and traveled to institutions that invited DeJong to be a visiting artist.

To an outsider, DeJong, the recipient of two Pollack-Krasner fellowships, appeared to be living the artist's dream. But in reality, he struggled to stay afloat financially. On top of his gallery job, DeJong had to clean apartments on the weekends to pay his bills.

Eventually, he quit the gallery to have more time for art, cleaning full time until he found more lucrative freelance jobs styling still-life photos for magazines and catalogs. (When DeJong became ill from years of exposure to toxic household products, he researched and developed natural alternatives. His recipes became the genesis for three books about safe cleaning practices. All were published well before the Green movement and are now in the Library of Congress).

Styling work came naturally to DeJong. His parents had made almost every garment, toy, and stick of furniture. He inherited their joy in making things and loved designing Christmas cookies for Martha Stewart and carving pumpkins for Good Housekeeping covers.

As DeJong approached the 20-year mark of an enviable career, he felt disillusioned with the politics and values of the mainstream art world. "I was starting to feel that I didn't matter as much as the artwork did." He did some soul searching and decided to leave his gallery.

Nurturing other parts of his life was important to DeJong, especially his relationship. (Now married, he and his partner have been together for 34 years). Pragmatically, there were still bills to pay; he needed to prioritize the future.

It wasn't easy for DeJong to relinquish his notions of serious art and walk away from the so-called glamour of an established art career. Some might say he sold out, but DeJong didn't have a trust fund or fallback plan like many of his artist friends.

A decade later, DeJong returned to making art. Now retired to Palm Springs, a city steeped in mid-century modern culture, he began thinking about garden flamingos made from concrete. "I love their buoyancy and flamboyance but wanted to elevate them out of their kitsch 1950s hot pink plastic iconography." DeJong managed to find some molds from the 1940s and taught himself how to make them, which was no small feat.

Memory and objects have always been themes in DeJong's work. "Objects rekindle the past and allow me to go back to when my family was still alive and present."

Once DeJong had the skills to work with concrete, he began to pour molds of everyday household items, taking them apart, then grinding and filling the insides. The scale of the resulting pieces is unexpectedly diminutive because they're the size of the object's interior, not the exterior.

After he’d compiled an assortment, DeJong realized the objects could be juxtaposed. In his towers, nothing is bound together. Each balancing act produces an off-kilter sensation, nudging you to see the items in a new light. "There's a universality to the mundane objects that, even when amassed, is still maintained.”

By rejecting the mainstream art world, DeJong discovered that making art on his terms was enough to satisfy him.

Now retired, he makes something every day. "I love making clothes for my husband and me. I sew. I love making a slipcover if I feel like it, for a couch that just sits outside."

Through making, DeJong expresses his creativity. Unlike many artists, he is unconcerned with his voice, identity, or recognition. "My work has always been kind of clinical, almost in an attempt to eliminate personal touch." He rarely even signs it. (You won't find much evidence of his early work online, either; he erased what he could).

Instead, DeJong is more interested in sharing what surprises him or makes him laugh and what his work might evoke in a viewer.

________________________________________________________________________

Judi Tavill had different creative aspirations. She never dreamed of being a fine artist. The idea never even occurred to her.

After graduating with a major in fashion and a minor in business, Tavill soon landed a job as head designer for the revived Lilly Pulitzer line in the early ‘90s. "I was a Jewish girl from Baltimore, Maryland. I wasn't a blonde preppy girl, but I knew who she was. And I was damned good at designing an outfit for her.”

At Lilly, Tavill did everything from silhouettes to illustration to prints. It was "initiation by fire" and set a precedent for how she would continue to approach her creative life: "If I want to do something, ultimately, I figure out." So when tasked with designing a swimwear line for boys and men, Tavill headed to the GAP, where she secretly measured boys' swim trunks in the dressing room.

Tavill thrived in fashion, traveling overseas three times a year and starting a line of her own. She thought she'd stay in the industry forever. But after seeing friends lose family members on 9/11 and the birth of her second child, Tavill had a change of heart.

As Tavill nursed her baby, she tried to figure out what she wanted to do next. "I dabbled in everything. I mean, I literally bought every supply for basket weaving. I was melting crayons." Eventually, she gravitated to ceramics.

Tavill can’t resist trying to get clay to do what it doesn’t want to do. As much as she hates how the material fights her back, she never stops pushing its limits. "I'm always trying to create ways to control something that's not controllable. And yet, I'm also tempted to let it just do its thing. It's that constant push and pull.”

When Tavill began to sell her work, her framework for making art was commercial. Her first line was unabashedly functional and reflected how she'd approached her fashion designs -- classics with a twist.

The timing was right. Etsy had recently launched, and Tavill began selling her work online and in fine craft shows and galleries.

Never satisfied, she explored new techniques, cutting and tearing the clay to give it more texture. When Tavill realized that people thought the new work resembled coral, an idea clicked.

Living minutes from the ocean, she envisioned a decorative series that would appeal to beach lovers in coastal communities. Art Insider and other companies asked Tavill to film process videos, and she eventually gained a huge following on social media.

Tavill had transitioned from functional to decorative art but was still frustrated. The price point she'd established no longer reflected the time and effort that such detailed work entailed. It wasn't getting the recognition it deserved.

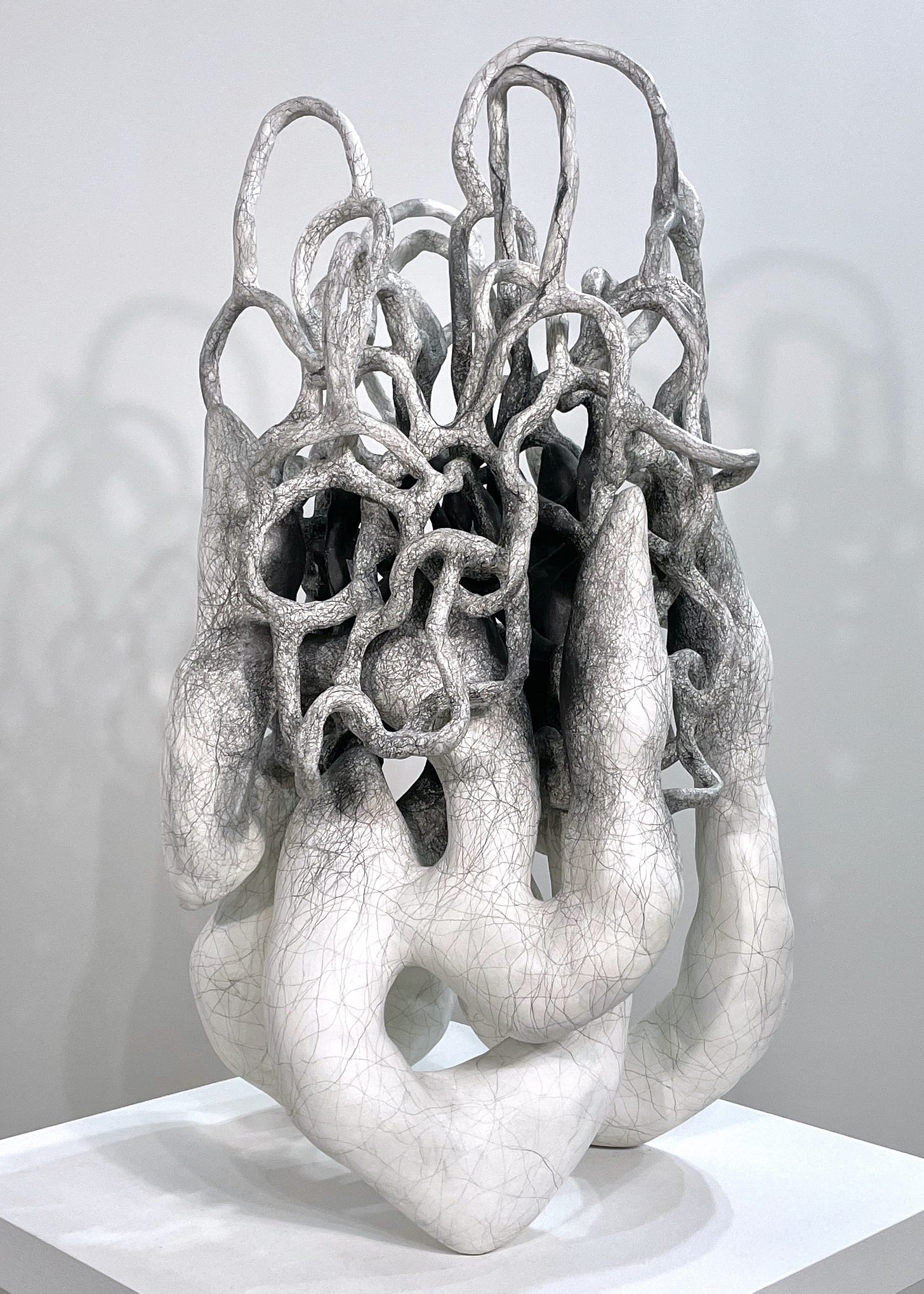

When she turned 50 in 2018, Tavill was ready to say something with her work. As she became more attuned to how BLM, Trump, and the pandemic were deepening the divide in the United States, Tavill noticed how elements of nature also struggle to co-exist. Vines strangle and suffocate trees; animals prey on each other.

More nature/human parallels became obvious to Tavill, including their structures and systems. Like trees, humans have cores, a protective layer, and appendages that turn into digits. Just as trees have roots, we are bound to the earth through gravity. Nature’s ecosystems and the body’s organ systems can thrive or become threatened by disease.

These ideas began to influence Tavill’s work. For instance, in Elevate, two stackable forms capture the duality between entanglement and connection. The stronger, more organized form assists the more precarious one, while lines reinforce their relationship. Nurture captures another duality in nature, protection vs. possession.

Tavill’s desire to express her voice coincided with an urge to make her pieces more sculptural. She added paper to strengthen the clay (it burns out in the kiln) and experimented with encaustic and wire. Her goal was to create a three-dimensional surface that she could continue to enliven through drawing.

Making this transition was a challenge for Tavill. The world of functional ceramics has explicit rules -- plates for eating can't leech or have crevices that promote bacteria. It's not typically acceptable to mix mediums or incorporate unconventional materials.

To move forward, Tavill had to break through the label that defines ceramics. Today, she is no longer "shackled" to her ceramic roots. She makes abstract sculpture that, for now, happens to be based in clay.

Tavill aspires to remain fluid. "Why chain myself to one thing? I want to say what I want to say, but there are various ways to say it. I'm not sure what that makes me. Maybe simply an artist?”

That letter to your parents -- WOW. What a beautiful connection you had with them, and with yourself, at such a young age.