ARTWRITE #20: Painting The Narrative

Jennifer Coates, Judith Linhares, Laura Karetzky, Ernesto Renda, Kyle Staver, George Towne

May 1, 2021

Our impulse to tell stories is as human as the need to consume them. It shouldn't come and go like a new trend. That's why I was so surprised to learn that the art world had rejected narrative art until recently.

The once-popular genre became passé in the early 20th century. Dusty historical figures and moralistic themes couldn't compete with the explosion of abstractionism. Once formal innovation took over, figuration was out, and there was no longer an "I", "she/he," or "they" in art. In essence, modernism whitewashed the subjective. There were exceptions (think David Hockney, Lucian Freud, and Alex Katz), but artists who wanted to tell stories, be it ancient or newly imagined, were swimming upstream.

While I struggled to believe that any art form could dismiss storytelling, for art students in the 1980s, the irrelevance of figuration, narration, or anything smacking of personal was a reality. In many art schools, there was no language for discussing narrative-based work. A friend who attended a prominent program in the 1980s told me her art history books included no figurative painters; whenever she tried to find ways to tell stories, she'd get fierce pushback from her professors.

Thankfully, narrative art (which to my confusion, is often used interchangeably with figurative art) is back in vogue. When I asked artists why the time is ripe, they spoke about the influential power of social and political movements from early feminism to BLM. Now that museums, galleries, and the media are embracing voices that have historically been absent from the conversation, there's a place for work that is subjective, personal, even confessional. Technology has also played a part by warping our experience of human connection. Social media has normalized the sharing of private experiences, but its curated and filtered content leaves us hungry for authentic engagement.

Along with a resurgence in narrative art comes a redefinition of the genre. Stories are no longer required to have recognizable plots, characters, or settings, nor are they limited to what the viewer sees on the canvas. Instead, we can locate narratives in the artist's socio-political identity and marginalization, creative process, dialogue with other artworks, and ultimately, the viewer's interpretation of the work.

All these possibilities are in evidence in Painting the Narrative at the National Arts Club from May 4 to June 26. The exhibition includes six American artists, all of whom I've featured in this special issue.

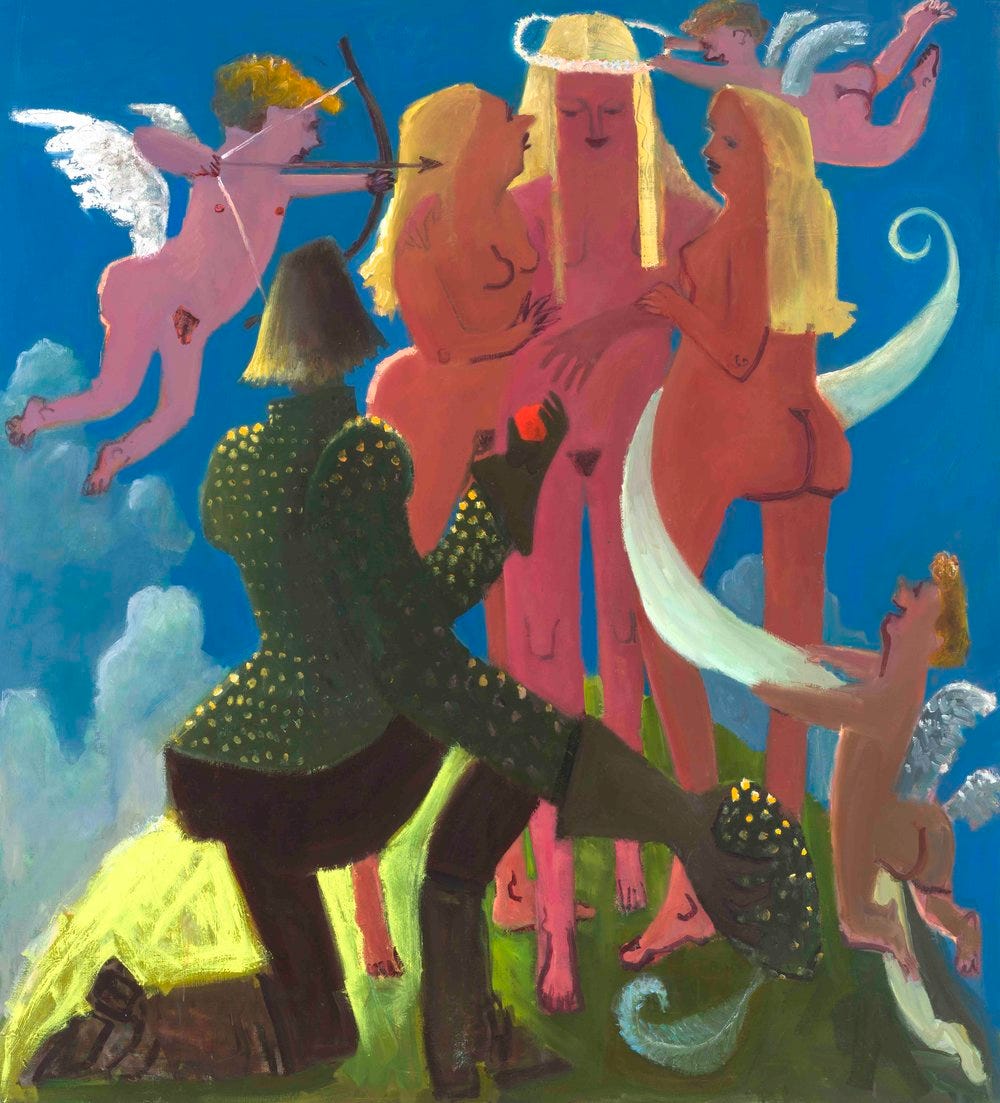

KYLE STAVER

Kyle Staver paints “the big stories.” Unlike the original narrative painters-for hire who faithfully rendered myths and Bible stories centuries ago, Staver reimagines them. In her hands, plot points change, characters become more human, and stories that felt generic or didactic take on new meaning.

In the past, Staver painted from experience (“me and my husband in the backyard doing nothing”), aiming to make personal stories universal. Once she flipped that equation by personalizing universal narratives, her work became less opaque. For Staver, painting is about communication and connection. She banks on some familiarity with the big stories so viewers will be alert to her tweaks and be “in on the crime.”

The first time I saw Susanna’s Hammock, I didn't know that Tintoretto's Susanna and the Elders and Courbet's The Hammock had inspired the curly-haired woman flanked by two tigers. I also wasn't familiar with the Bible story that Tintoretto and many other painters referenced. Once Staver filled me in, I learned the story, and my take on the painting exploded.

Staver’s Susanna isn’t on the verge of becoming the unwitting victim of men’s lechery and lies. The elders don’t even appear in the painting. In their place, two tigers, eyes gleaming, stand in attendance (perhaps a reference to the attendants Susanna dismisses before bathing in the Bible story). Naked, except for a gauzy throw that conceals nothing, Susanna revels in primping, twisting a long string of pearls like a saucy flapper. Unlike Tintoretto’s and Courbet’s women, Staver’s Susanna is not only free from the male gaze but reclaims it as she admires herself in a hand mirror. No false accusers will be put to death, and virtue doesn’t need to triumph because this Susanna isn’t at risk.

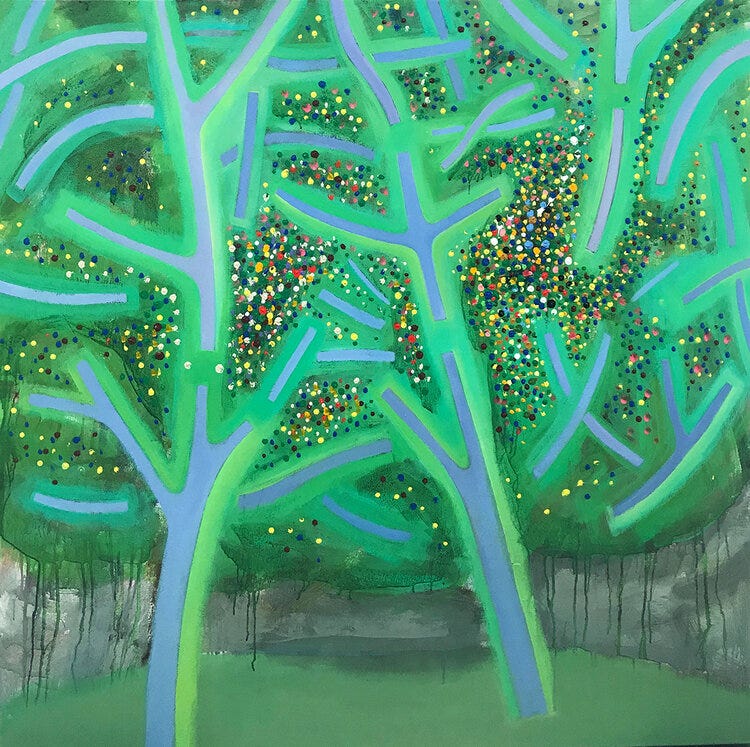

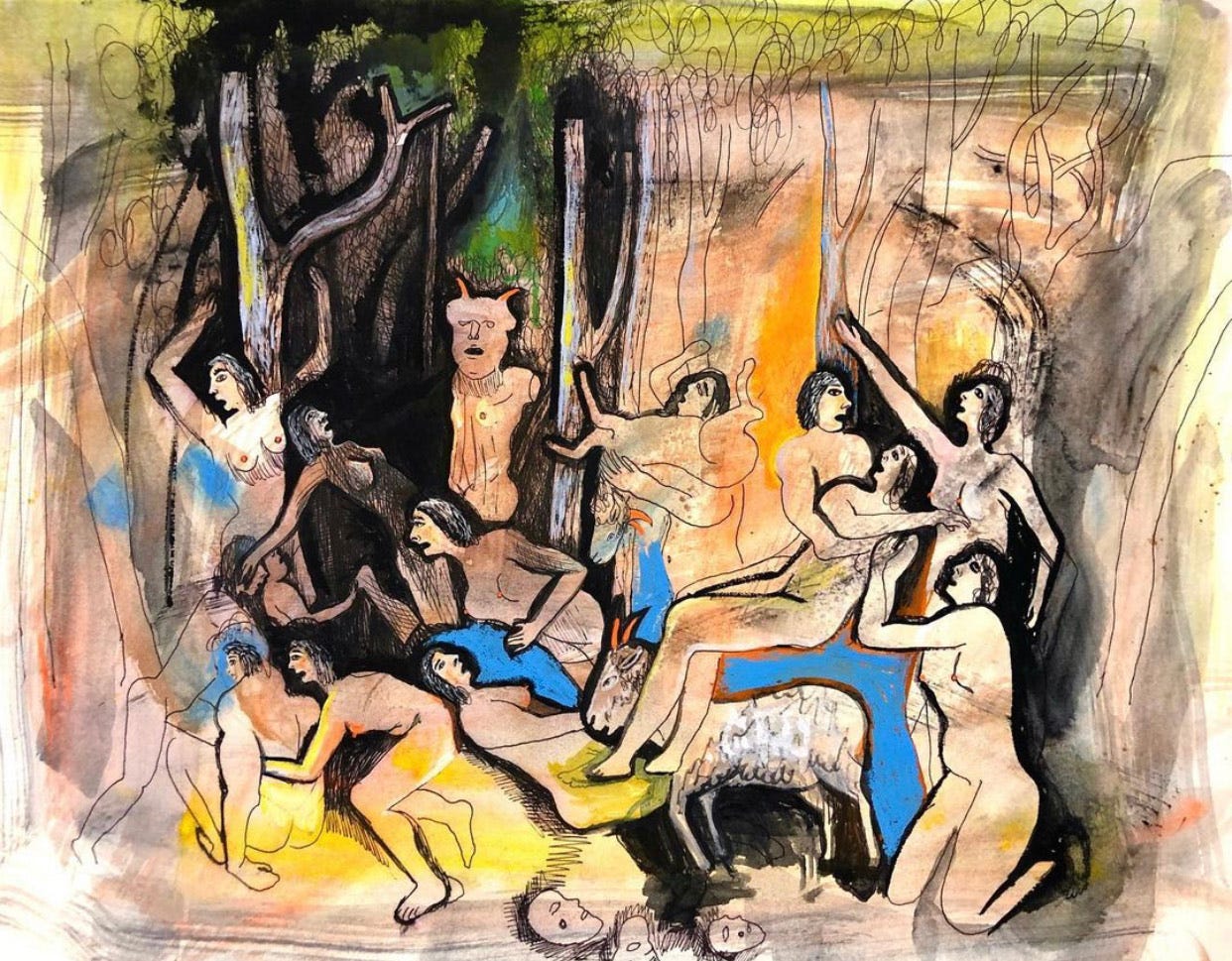

JENNIFER COATES

Jennifer Coates is fascinated by pastoral painting. Her trees often glow with an otherworldly quality or throb with invisible life. In her forests, half-animal, half-human hybrid characters suggest the ultimate human merger with nature.

Like Susanna's Hammock, Coates's Triumph of Pan also pays homage to earlier narrative work. These paintings reminded me of my favorite experiences teaching Shakespeare to Middle School students. Once my students would set their scenes in contemporary settings,Shakespeare’s language would come to life.

Coates studied Nicolas Poussin's and Picasso's paintings and Leon Kossof's Poussin-based series of etchings, making four works on paper in response to their images and referring to them to ensure that the geometry among the figures echoed in the trees and the painted ground underneath. When she got to the larger paintings, she was no longer looking at their work but at her paintings on paper.

Coates’s composition is more streamlined than her predecessors, with acidic, artificial hues to darken the mood. There's no evidence of the world beyond the grove; the sun may never rise. All-female revelers pay tribute to an androgynous Pan in a moonlit grove of trees that appear to be participating or perhaps urging on the festivities. This bacchanalia captures the human desire to lose ourselves in feasting and fornication. Notably, the artist painted it during the pandemic when we couldn't indulge the urge to party.

Forms and figures reveal themselves to Coates through a process of layering atmospheric color and texture: "I feel like I am digging for the scenes, isolating forms to make figures, branches, and a sense of both encrusted surface and receding space. I know vaguely what I want to find, but I'm teasing it out, searching for a story like a diviner reading tea leaves." The merger of figures and abstract elements that result from Coates’s process feels contemporary and timeless.

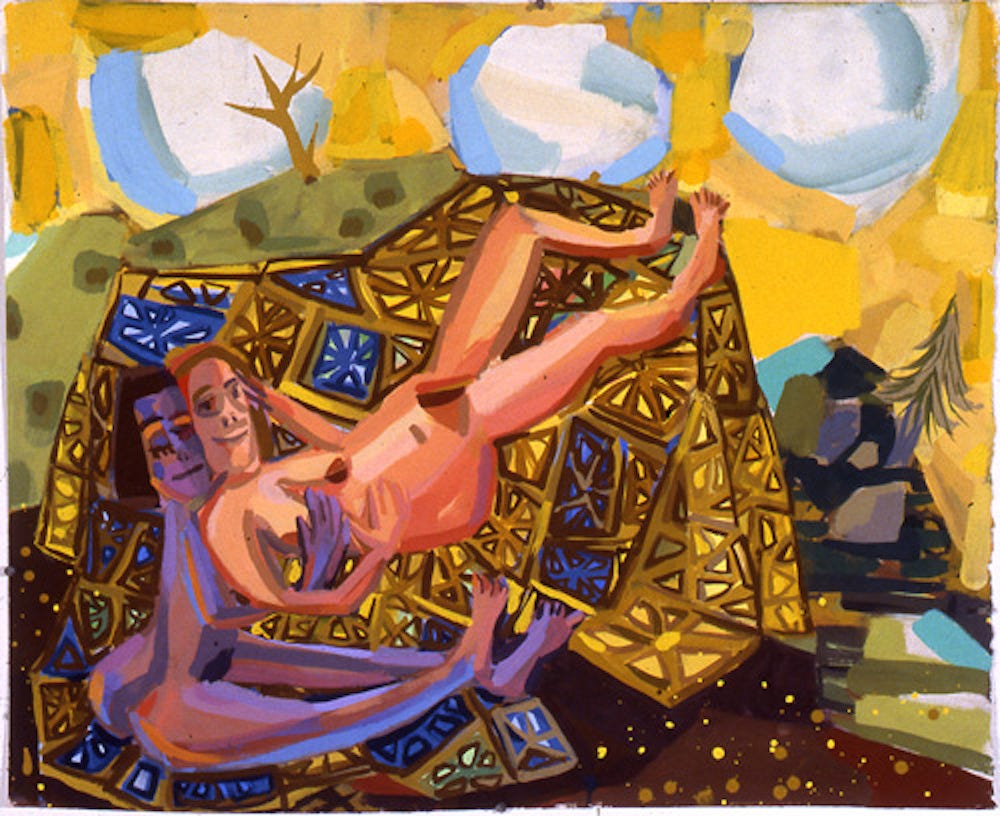

JUDITH LINHARES

The painting process is also an act of discovery for Judith Linhares. Her imagery reveals itself through the physical act of putting down color and "reading into" these gestures, a process Linhares entrusts to her body, not her mind. "I don't want to be in the situation of painting an image that I cooked up in my head—that would be too much like illustration." Linhares has similar expectations for viewers whom she hopes never respond to her work from "the neck up." Like Staver, she wants them to feel the power of an immediate experience, not a cerebral one. It's also up to viewers to interpret the stories she tells in her painting.

The artist’s "big project has been to examine the preconceived images of women in cultural material," an endeavor that matters because she has a personal stake in it. Fall Into Morning exemplifies how Linhares reworks a classic trope. Her fallen woman hasn't lost her innocence or fallen from God's grace. Instead, she's relaxed and content as another woman blissfully catches her in her arms.

Linhares's women appear to have no physical limits. She often renders their bodies in anatomically impossible positions, using brush strokes to emphasize musculature. As they dig holes, haul buckets, and build fires, their nakedness signals freedom and strength rather than objectification.

In the world Linhares creates in her paintings, women always appear to be at peace with themselves and each other. They cohabitate in nature, living in outposts that often feature an element of pattern like the crocheted granny square design covering the geodesic dome in Fall Into Morning. I like to think of this recurring motif as Linhares's sly nod to Pattern and Decoration, a movement that defied the limitations that men put on art.

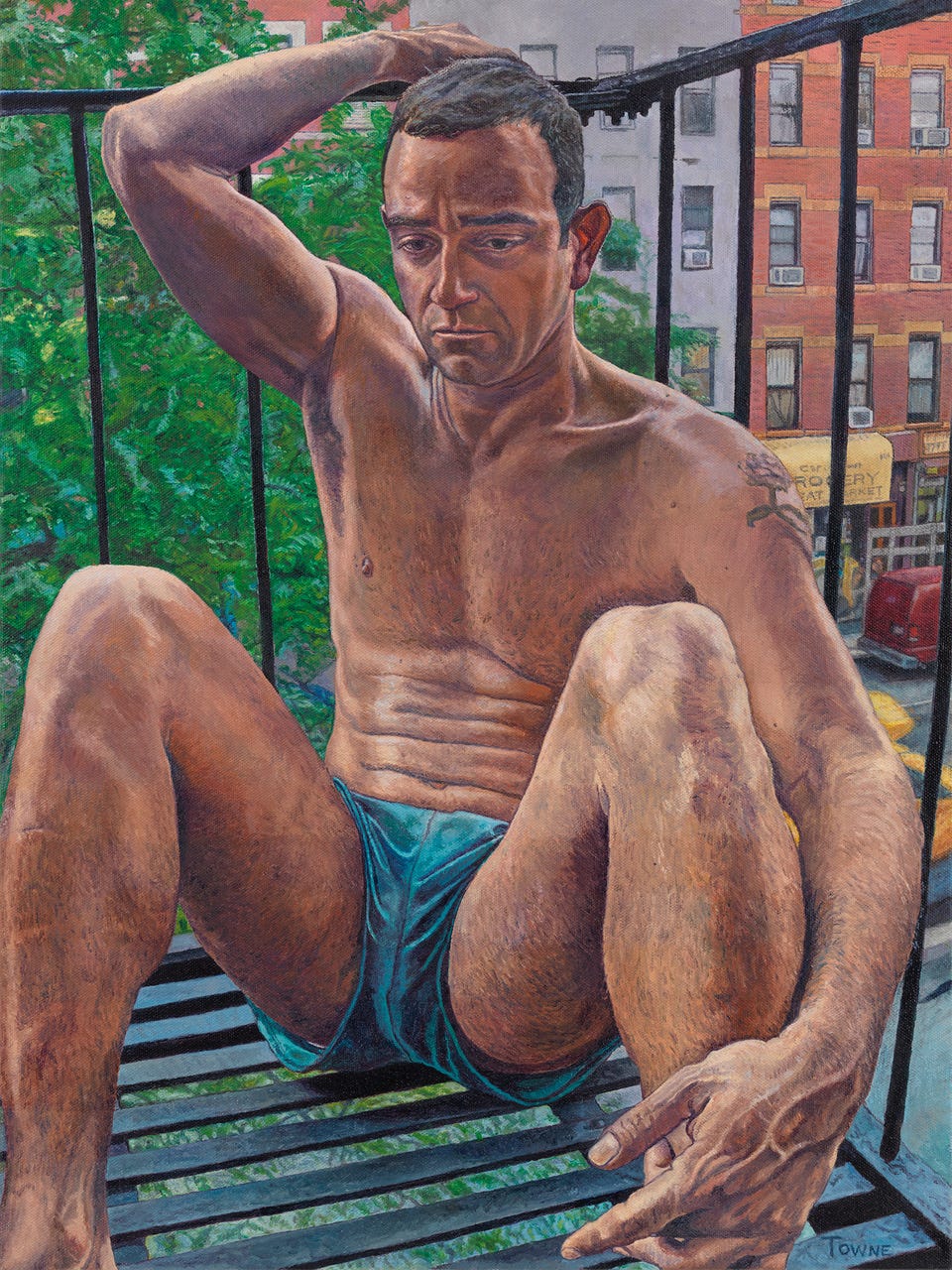

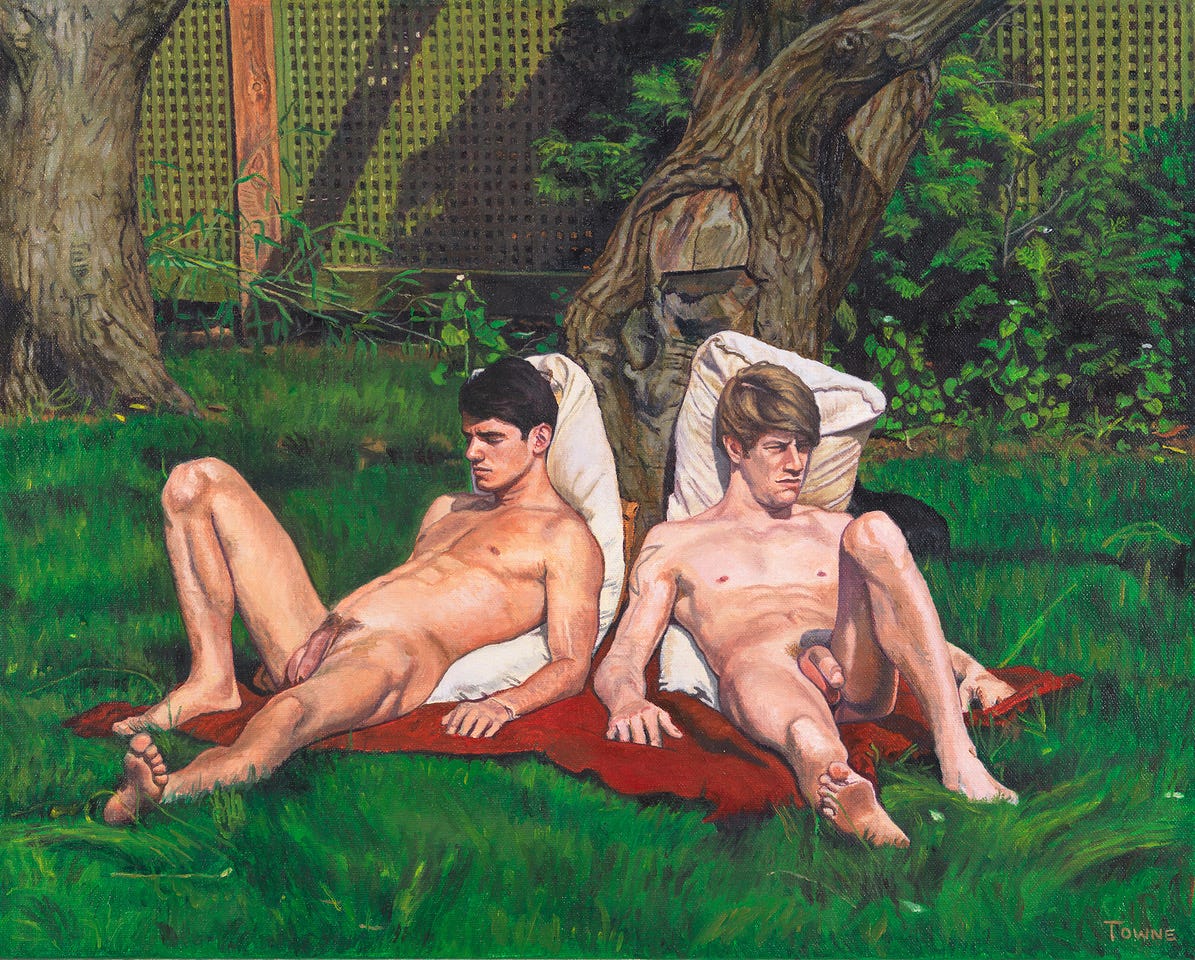

GEORGE TOWNE

Because sexuality defines gay men's otherness, a lot of gay art ends up being erotic. That's not how I experience George Towne's paintings. The artist acknowledges that desire and an obsession with gay male beauty are at the root of his portraits of friends or former lovers, but the tenderness he affords his subjects makes them more than just objects of his desire. "People I love have come and gone in my life, and loss has not always been easy for me to deal with. But if I have been able to paint them, it's like capturing them and holding them with me forever."

This kind of emotional urgency distinguishes portraits like Nando - Fire Escape. When Towne painted his friend in skimpy shorts on a Hell's Kitchen fire escape, he was aware that Nando felt self-conscious. The image is undeniably homoerotic, but what comes across most strongly is Towne's compassion for his subject's vulnerability.

Growing up, Towne never saw gay men acting in television shows, running for president, or holding hands in public. He didn't know anyone else who was gay and associated homosexuality with ostracism and later violence. As an HIV-positive adult, safe sex rules made it challenging for Towne to experience the freedom of unprotected sex until recent treatments became available. And as an artist, he's witnessed the censorship of artists like Robert Mapplethorpe and David Wojnarowicz and the art world's indifference to work by gay artists. (The success of painters like Louis Fratino, Jonathan Lyndon Chase and Salman Toor would have been unthinkable a decade ago).

Towne's painting is a response to the restriction and suppression that defined his identity. Instead of directly depicting these experiences on the canvas, he imbues his work with the feelings of freedom that he didn't experience in his own life. In his portraits of men, Towne is safe to express unabashed desire. You can also see it in his reverence for the casual ease with which couples express their intimacy.

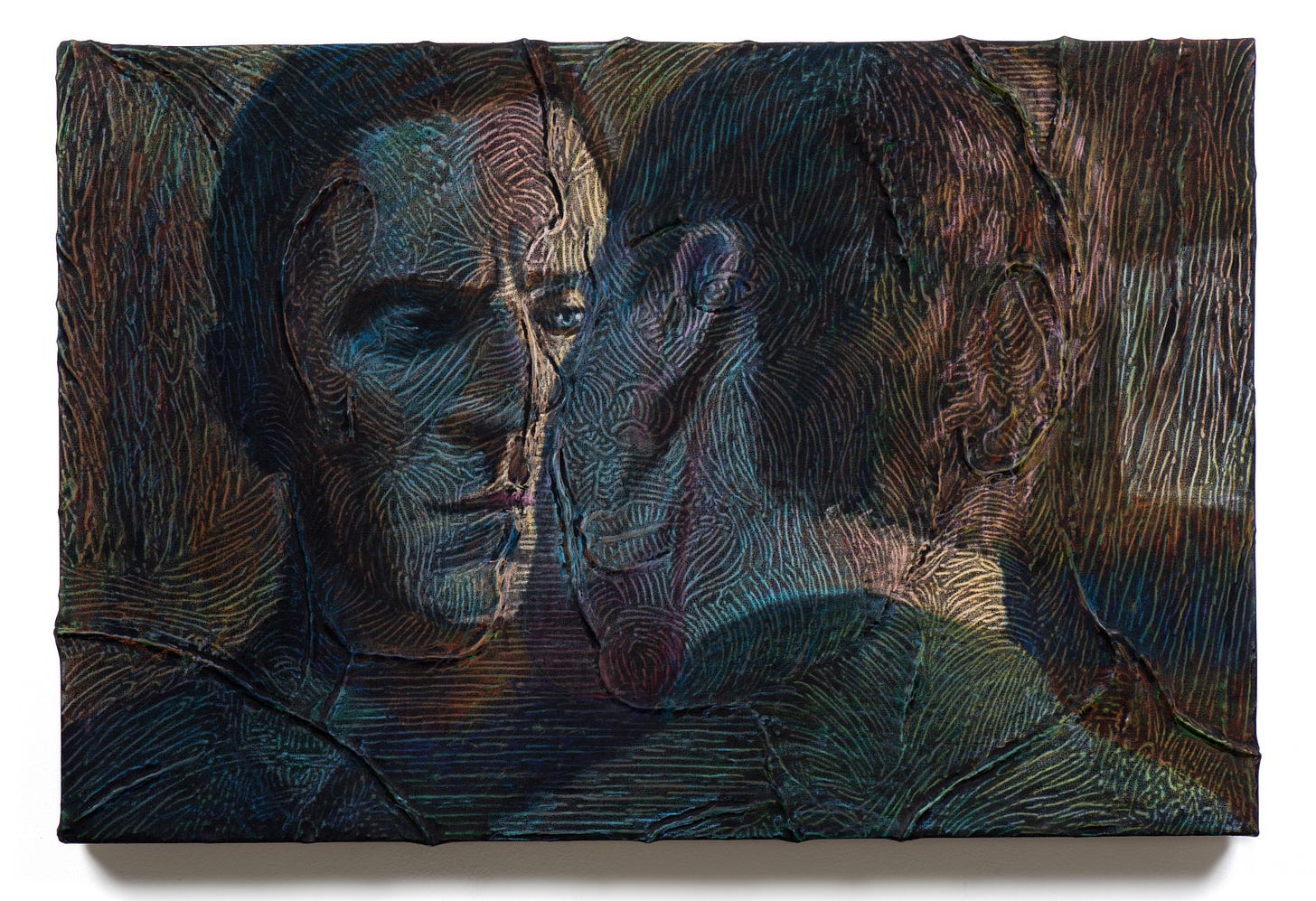

ERNESTO RENDA

Film history is replete with art-inspired images. Painters from Caravaggio to Hopper have influenced how shots are framed and lit. Ernesto Renda reverses that concept by looking to film to inform his artwork. When he’s not using cinematic compositions to frame images from his memory or imagination, Renda juxtaposes two successive screenshots from a film sequence to create an image that resembles a glowing TV screen.

For Renda, taking screenshots is a preparatory process similar to drawing. His daily practice usually begins on YouTube, a means of visually journaling back to films from his childhood to locate resonant images. When choosing, Renda stays clear of anything iconic. "If you take a very recognizable image from film, you're pigeonholed into a structure where you're just reproducing an image."

Renda is interested in how the language of film informs meaning. His 2020 Over The Shoulder series focuses on point of view and how the camera's position can manipulate our identification with characters. In I feel like a turnstile to the White Party and No one will ever love you like I do, Renda’s juxtaposed pairings create unexpected optical correspondences.

Recently, Renda has been working with cutaways, a technique that allows the viewer to avert their gaze from intense imagery. With Waves Crashing at Garrapata Beach, Renda deconstructs the finale of a popular HBO drama, a fight cutting to waves crashing on a beach, then combines the two images so the viewer can no longer disassociate from the violence.

The rubbing process Renda uses to create his images is itself a narrative of erasure. Just like characters in fiction and film who never succeed in masking whatever defeats or defines them, the ghosts of Renda's original images haunt his new ones. It's the kind of intertextuality he relishes: "In the realm of figurative painting, you can't draw more than a few lines without referencing something. That's the space that figurative painters love to play in. We love to see ourselves in relation to other painters."

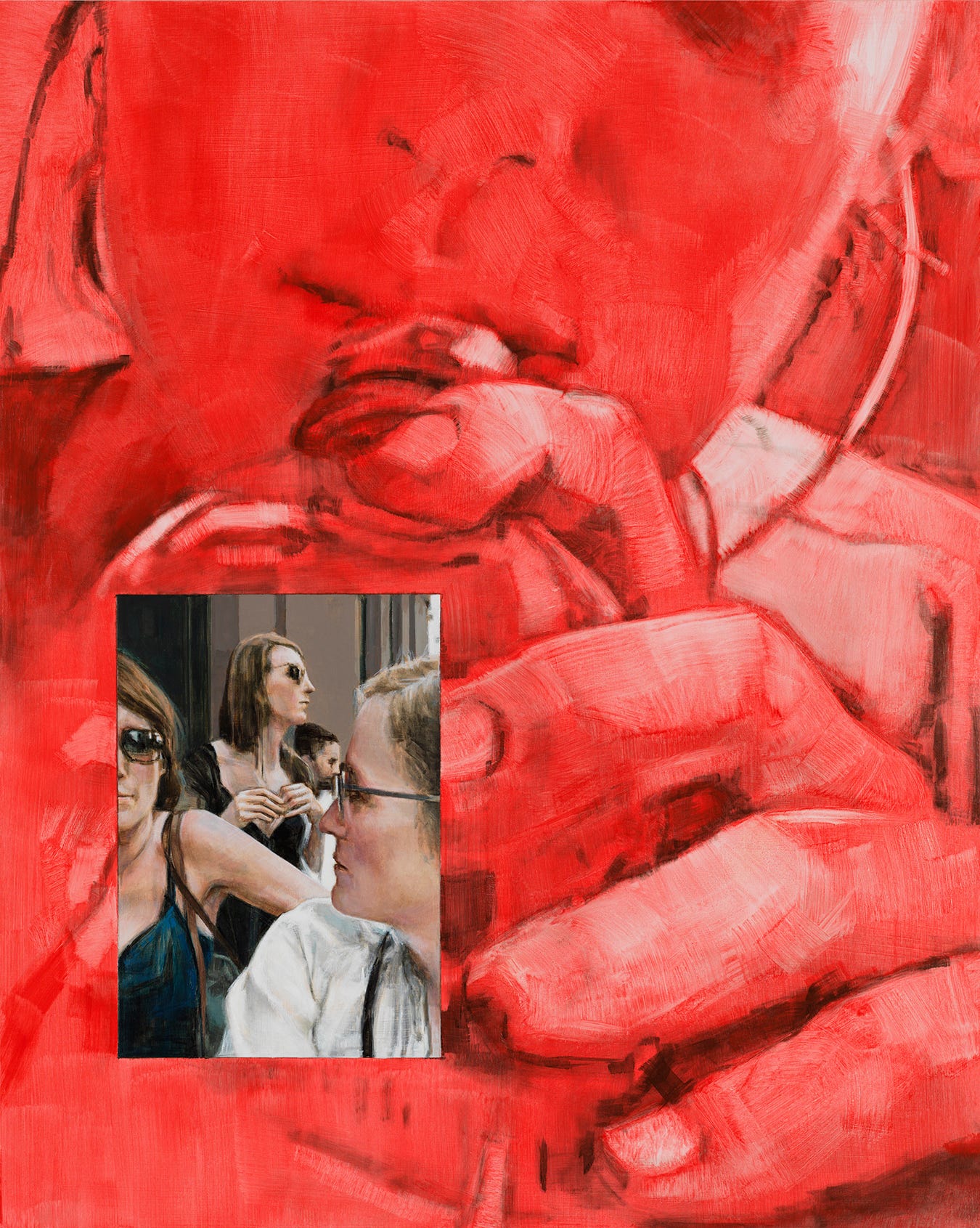

LAURA KARETZKY

While Ernesto Renda uses YouTube as a form of drawing, Laura Karetzky's smartphone is her sketchbook for capturing real-life encounters. When a moment or situation doesn't quite add up or has multiple meanings, she reaches for her camera. "Real life is densely rich, and I feel compelled to try and make sense of it daily."

Back in the studio, Karetzky transforms these ambiguous moments into compositions. At only 5' 1", the artist works in a scale that allows her to reach the entire surface with fluid gestures and take it in without shifting her eyes. This connection between her body and painting is what makes Karetzky’s work feel so intimate. At times, I feel like I'm spying on a private moment.

The search for simultaneous narratives is foundational to Karetzky’s work. Like Renda, she’s also fascinated by the visual language of storytelling and how it can push the limits of narrative art; boundaries merge when stories are in proximity to each other; narratives bend or change according to our perspective.

Karetzky’s embedded window paintings examine how technology has redefined the mechanics of perception. "Our brains are learning to acclimate into processing multiple perspectives at once, like a fly with those many eyes." These paintings capture how when inside the visual frames of Zoom and Facetime, we're two people at once. Toggling between perspectives, we watch how we present ourselves and watch ourselves being watched.

Perception and optical illusion are also at play in Karetzky’s paintings of paintings. Looking at the four iterations of her bananas feels like opening Russian dolls or playing a visual game of telephone. In her studio, Karetzky looks to the work that surrounds her for camaraderie. By making one of her paintings a character in a new piece, she creates a possibility for conversation with her subject matter: "How do I flatten? How do I separate? How do I force the tensions?"

Just as a memoirist selects and shapes her experiences to craft a narrative that has universal meaning, Karetzky uses visual images to tell personal, relatable stories about community, family, home, and the self.