ARTWRITE #19: Intention

Lenia Hauser, Kysa Johnson, Mary Valverde

3/20/21

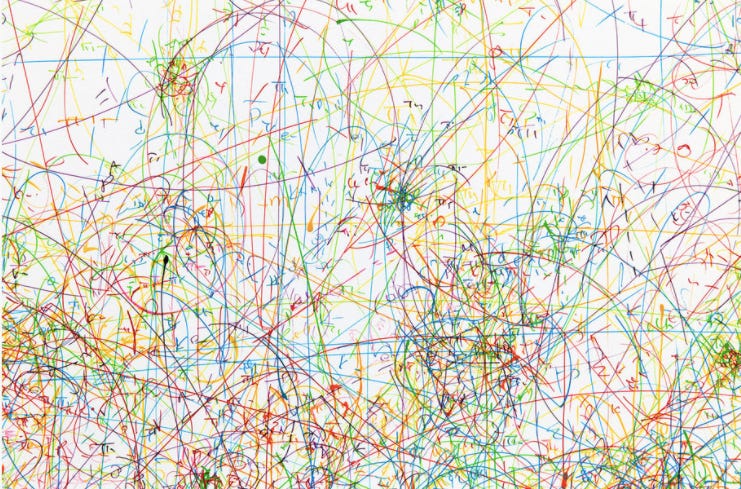

Confession: When I posted the painting above on ArtWrite last November, I knew nothing about Kysa Johnson. A friend had sent me a link to her Instagram page, and I loved the paintings that reminded me of when I was a kid and would cover a drawing with black crayon, then scratch out a design that revealed the colors beneath it.

I like that art can speak to me without explanation. That's why I don't read the wall text at museums or galleries until after I've seen the work and am always on the fence about audio tours. I also rarely read artist's statements, but that's mostly because I find them incomprehensible.

When my friend later told me that Kysa's work is rooted in science, I was surprised and went to her website. The connection between the technical jargon in the titles and the dreamy images baffled me. I wondered if Kysa would be upset by my reaction and wanted to know how much she and other artists cared about people understanding their work. So I decided to reach out to some artists to learn how they think about intention in their art.

Kysa, along with Mary Valverde and Lenia Hauser, agreed to be interviewed. All have clear ideas about what they want their work to express and claim to be okay if viewers don’t understand it. This surprised me. If Kysa wants her paintings to reveal how man's relationship to oil has resulted in war, and I don’t pick up on that, then it seemed to me that she’d hadn’t realized her intention.

But art isn’t about right or wrong answers. Kysa, Mary, and Lenia know this. When they describe how they hope viewers will experience their work, their language becomes intangible. They want it to affect viewers, to touch them in elusive ways that artists' statements or audio tours don’t mention. To have an experience that can't be explained by the words on the wall.

I'd love to know what you think. Do you feel art should stand on its own without text to explain it?

Born in Illinois, KYSA JOHNSON now lives and works in Los Angeles. Her work explores patterns in nature, using microscopic or macroscopic “landscapes” to depict physical realities invisible to the naked eye. Often these micro patterns are used to create compositions that connect to related concepts.

Kysa grew up feeling frustrated that no one in her Mormon community had any regard for curiosity. “They just believed what they were told, even if it didn't make sense.” When Kysa pushed back, it was a problem. “Sometimes, I was told that Satan was telling me to ask questions.”

At 13, she had an AP chemistry teacher who made her feel about science the way she was supposed to feel in church. Kysa had always loved nature, and this teacher captured its mystery and magic. She began to question the unbending, illogical way Mormonism had taught her to engage with the world while also learning that she could interact with it more openly. For the first time, she was encouraged to be curious. This was the beginning of Kysa’s obsession with science.

All the while Kysa was drawing, and by the time she got to art school, she still hadn’t figured out how to merge her two loves: drawing and science. That changed when she saw photos of subatomic particle decay patterns in The Tao of Physics. Struck by the invisible beauty of these trail-like marks, Kysa had an epiphany: “The physical universe was drawing and doing it better than I ever could.”

Inspired, Kysa memorized eleven of the infinite patterns and adopted them as a mark-making vocabulary for her drawing. Like rendering a "W" or an "A" with fat, thin, tall, or short lines, Kysa has unlimited options as long as she maintains the relationship of the patterns' lines. Each version looks different, but the integrity never changes.

Kysa also deliberately includes the relevant scientific notations. These pies, K's, P's, alphas, and omegas remind viewers that her drawings represent actual patterns foundational to our physical world. "Without science, we wouldn't be aware of their existence."

For the past two decades, Kysa has returned to her key. When removed from their scientific context, the particle decay patterns become landscapes that illuminate the breadth and limits of our knowledge.

Kysa wants her work to provide a greater understanding of humanity’s place in the universe. When Nancy Littlejohn Fine Art in Houston invited her to do a solo show, Kysa chose to focus on man’s relationship to oil and how it has unleashed progress and horror.

Crude examines the evolution of oil from the creation of hydrocarbons in the ultraviolet light of nebula to the fossilization of phytoplankton, "to its transformation into a gooey but potent liquid substance that has defined our recent history, to its extraction by humans, to the destruction and chaos resulting from oil wars."

For Crude, Kysa created a new visual vocabulary based on petroleum’s plankton and chemical components; (phytoplankton are microscopic sea creatures whose fossils become oil). Her symbols also reference Monet’s water lilies series in unexpected ways. Beyond Monet’s obsession with his garden, the water lilies were also a personal response to the mass tragedy of the First World War: “Yesterday I resumed work,” Monet wrote in 1914. “It’s the best way to avoid thinking of these sad times.”

World War I was the first oil war and the beginning of widespread public use of oil-based technology. Scientists today expect the world to run out of oil by 2063, only 205 years after the first installed oil well in 1858. Amazingly, it took nature millions of years to create oil but barely two centuries for humans to deplete it. The 10,000,000/205 ratio of Crude’s central installation captures this irony: the large rectangle represents 10 million years, the center stream 205 years.

Although Kysa’s work has always been representational, some perceive it as abstract. (Her kids like to accuse her of making scribble drawings) People will say how a painting looks “just like space” when it is an image of space Kysa copied from a Hubble Telescope image.

That’s why Kysa never gives her work poetic titles (although she would argue that reality is highly poetic). Instead, she precisely lists what the viewer sees. Her titles and scientific notations are the “breadcrumbs” Kysa uses to lead viewers to an understanding of her work. “And if people enjoy it without understanding it, I guess I've done my job as an artist, and it’s why I draw and don’t just write down ideas.”

The beauty of the universe moves Kysa, and she wants to share this feeling. She also hopes to broaden perspectives. "If we can look at things from different viewpoints, whether it's from zooming out and zooming in on time, scale, space, or history, then we can engage with each other and the world more respectfully. Perspective. We all can benefit from a larger perspective. That's what informs my intent."

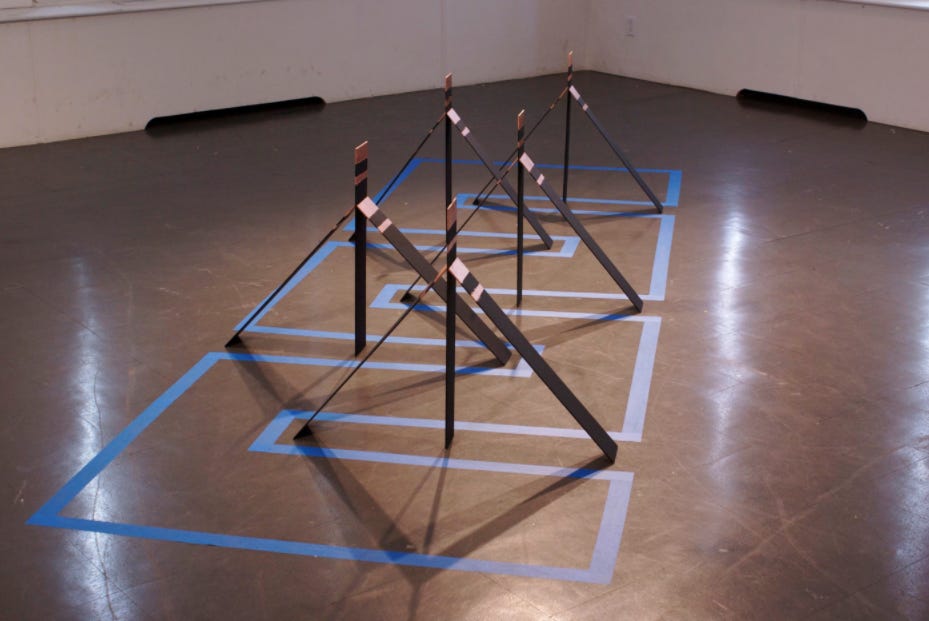

MARY VALVERDE is a New York-based interdisciplinary artist. Working primarily in sculpture, drawing, and installations, she explores rituals, cultural beliefs and practices, and indigenous visual languages.

Mary's work celebrates pre-Colombian geometric patterns and symbols. This visual language has endured for millennia, distinguishing Andean architecture and reappearing in textiles, metal, and stonework. Mary's abstract installations also explore the value of ancient and sacred sciences. Abstract concepts that traditional science can't prove (magical realism, dark matter, the invisible vibration of color) all inform her work.

Despite her passion for these subjects, Mary doesn't expect every viewer to recognize their meaning in her work. "Some may feel art doesn't need to be explained or don't want an explanation to take them out of their experience." Some will get her cultural references, while others will respond to the work's formal qualities. Mary considers both approaches equally valid: "Someone can receive only the formal, like what color or shape it is, how it's constructed and what it's physically doing in the space ... But similar to someone being bilingual or understanding a different vernacular, if you know color codes or what certain references are in terms of materiality, what a cultural reference to binding or weaving is, that's inside information, and I'm okay with that."

By favoring viewers who are familiar with indigenous culture, Mary alludes to her own experience in academia. "I learned Western European art history, and on my own, I looked deeper into art history and culture history of my ancestral country and the diaspora." If viewers want to learn more, they can always do research or look to Mary's titles for clues to meaning.

One of the in-the-know symbols viewers will recognize is the Chakana. Often called the Incan cross, this symbol for the divine has been a cultural thread since pre-Columbian times, appearing in architecture, pyramid construction, and adornment. Today, you can see it in contemporary textiles, fashion, or on the frames of paintings.

The wall piece in Huaca features a Chakana and a patterned floor piece inspired by the Huaca de la Luna, an ancient Peruvian adobe temple. The altar-like design of the floor piece prevents viewers from contemplating the Chakana head-on. Instead, they have to take the time to move around the altar. This piece was created for the Latinx Abstract exhibition at BRIC in Brooklyn and is currently on view until May 2.

Like most of her work, Huaca is ephemeral. The nine columns come off the wall in modules that get folded into packs secured with bookbinding tape. Although Mary's work may appear seamless or simple, it requires labor-intensive math, sequencing, and construction similar to solving a giant mathematical puzzle.

The internet can elucidate the references in Mary's work, but it may not be enough. "In unwritten languages or those that use pictorial symbols, words are not limited to one definition." A triangle can mean points to the heavens; the word for nose may be translated as where to get breath. Meanings can change depending on context or pronunciation. To appreciate a symbol fully, knowledge of the culture or language may be necessary.

Growing up in Queens, the daughter of Ecuadorian immigrants, Mary’s grandmother spoke Quechua, but she only spoke Spanish and English. Her mother kept the family's culture alive through food, but it was her visual vocabulary that Mary would later recognize as a distinctly indigenous aesthetic: "We would have parties, and my mother would organize napkins in a half-circle. The arrangements of everything were always symmetrical." As a teenager, Mary traveled to Ecuador and discovered visual parallels in how street vendors displayed stapled lotto tickets or candies, fanning them in half circles or other symmetrical patterns.

At the Casa de la Cultura in Guayaquil, Mary saw pre-Colombian artifacts that were similar to those she'd seen as a child in the vitrines of dark rooms at the Museum of Natural History. Out of context, these works appeared dead. "They looked like objects of ancient ruins. Like these people didn't exist anymore." At the Casa de la Cultura, the collection came alive. That's when Mary realized: "This is who I am. This is what is missing. This is where I am from. This is part of the language that I don't understand."

Art became the language for Mary to express her identity and a means to reclaim the agency of her ancestral history and culture. "People should be able to tell their own stories, and those stories should not be relegated to mythologies because someone outside the culture cannot understand their significance."

Mary believes art should be a visceral experience. Whether or not people fully grasp the richness and complexity of her work ultimately doesn't worry her. "There's a really wonderful connection between ancient cultures of many places from Egyptian to Arabic, to Chinese, Tibetan and Moroccan, to South American, Aztec, and Native American. All have this rich understanding of geometry, the cosmos, and how they can be implemented in everyday life and adornment. No matter where you're coming from, it's going to touch your subconscious in some way."

Lenia Hauser is of German and Swiss descent and resides in Halle, Germany. Her abstract work reflects an interest in geographical structures and the ground beneath our feet. She builds her paintings with amorphous forms reminiscent of children's puzzles.

I want to understand what holds our world together. The small and the mundane. The large and the inexplicable. The complexity and the interlocking of all processes. I seek stability in the ground beneath my feet, the rituals of living, and invisible physical forces.

When I was three, there was an earthquake in my city of Remscheid, Germany. Even though there was no major damage, it embedded in me a diffuse feeling of insecurity and fear. Today, I still feel the echo of this shock: the realization that nothing lasts forever, not even the ground beneath our feet.

After some detours into journalism, I decided to study graphic design, specializing in illustration. I was already seeking stability by learning about physical structures and noticing my attraction to textures, such as thick paint application on abstract paintings and the flaking and cracked paint on facades. Two years ago, after the birth of my first child, my life and priorities shifted. It became clear that I only wanted to do abstract paintings, the most sincere and deeply felt expression I can imagine.

I've always been a person who does not feel entirely at home in my body, "more soul than material," as my father likes to say. This does not mean I despise my body, only that my focus is spiritual. I'm still learning how to connect my mind and body to ground myself. The older I get, the more I seek what Germans call Sehnsucht, a longing for rootedness, and my paintings are a struggle to find it.

Sehnsucht explains my fascination with the irregularly shaped sidewalks and streets in Halle, the medium-sized city where I live. I walk a lot, internalizing these man-made structures that hold our cities together and navigate our everyday movements. Even though I rarely sketch them, they subconsciously creep into works like Stream, pavement studies from around my city.

So-called "top shot views" from cameras and Google Earth occupy me just as intensely. Works like Floating Islands provide a simultaneous impression of a close and far look at something that seems to be landscape and organism at the same time. It also captures my excitement with "self-similarity," the phenomenon of bodies, quantities, or geometric objects having the same statistical properties at different scales.

My process is immediate, functioning entirely from an inner urge that announces itself sometimes as a diffuse gut tingle or pulsating energy. It is a physical need, like thirst or the need to pee. In the studio, I let this urge run free. I spontaneously choose colors, brushes, and painting grounds and let a first texture and gesture happen. If I had to define an intention at this point: I want to let out the pent-up energy, like a spontaneous explosion.

After that comes the great flow. The most important thing in this phase is not to fix thoughts or acknowledge will or doubt. I made Raw Fields in this flow and can't remember when or how. This fact surprises me every time I look at it.

The main thing is to let a work arise in itself, not to reproduce any image of my mind thinking about something. Each form, texture, and color should intertwine, similar to a small ecosystem with meandering rivers, eroding mountains, or bird flock movements.

I have confidence that viewers intuitively connect with my work. It’s not necessary to understand the intention behind it. I don't display titles or text in exhibitions because I don't want to interrupt viewers' initial intuitive or emotional impressions.

In Undergrowth, I was interested in creating an energy exchange, like a spark that jumps from one thing to another. Many viewers see a seed sprouting even though I had no plant models while painting. To some, Green Sky Falling looks like a park they can enter; the forms lying at the edge lead them into the picture where they can wander.

In Bottom, some see dancing people holding hands or even a tree’s gnarled branches in the sunshine. I like being told about these different associations even when they don't follow the path of my intention.

When people learn their understanding of my work does strongly connect to my intention, they are surprised. I find this funny because it shows the myth that one has to fight to understand art.

The most honest intention for my work is to be close to people. I want my paintings to radiate warmth and closeness, to say: "Hey you! Come closer. Let go of all worries. Everything is good here." I want them to have a grounding and balancing effect and lead people to themselves and their peace.

Marriage of art & mathematics is totally my jam. Loved discovering these new artists!