3/6/21

I'd happily be a fly on the wall in a dance studio, costume shop, or recording session. Give me the option between going to a rehearsal for a new play or seeing it performed, and I'll opt for the rehearsal.

I like to watch artists develop ideas, solve problems, and wrestle with their creative demons. That's why I've always loved behind-the-scenes books, documentaries, and podcasts.

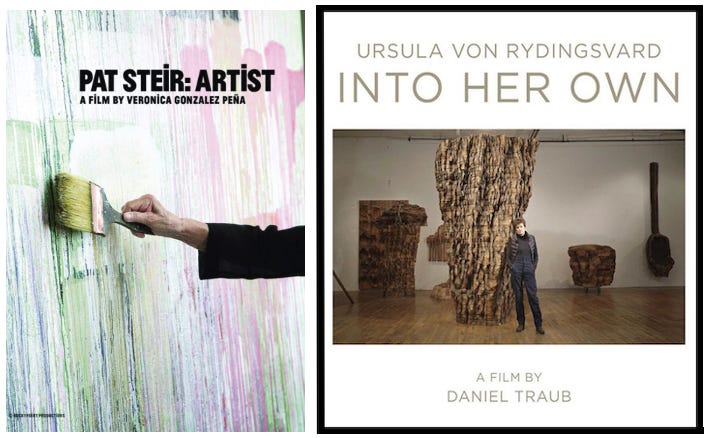

I recently watched two documentaries that provide an inside look at the creative process: Veronica Gonzalez Peña's Pat Steir: Artist and Daniel Traub's Ursula von Rydingsvard: Into Her Own. Both explore the drive to become an artist. Together, they make a fascinating double feature.

Each film profiles an acclaimed woman artist; neither is a household name. Steir, an American painter and printmaker, is best known for her dripped, splashed, and poured paintings. German-born von Rydingsvard is one of a small number of women making sculptures on a monumental scale.

As a child, von Rydingsvard spent five years living in Polish refugee camps. Her father, consumed with anger, physically and verbally abused her. Somehow von Rydingsvard managed to redirect her father's intense hatred, redefining herself "as something other than stupid and lazy and worthless."

Steir had a complex relationship with her young parents. Although her father introduced her to art, he was jealous and unsupportive of her talent. Her mother suffered from depression. Aggressive and tenacious, Steir was always aware of being the strongest member of her family. When her mother likened Steir to the evil child in the film The Bad Seed, she felt empowered by the insult.

When Steir arrived in NYC in the mid-'60's, the male-dominated art world rejected the idea that women could be abstract painters (as if they lacked "the abstract gene," Steir jokes). Even though she was fearless and saw herself as "genetically privileged to fly over problems," Steir was surprised by how much harder it was for women to become artists.

At 33, von Rydingsvard extricated herself from a dangerous marriage and moved with her young daughter to a cold, raw Soho loft. This was 1975, years before the neighborhood was cool. Fiercely determined, she relied on food stamps, found work, and supported her daughter as a single mother.

Interestingly, the art world had changed in the decade since Steir's arrival, and Von Rydingsvard found inspiration in knowing that New York was home to so many other women artists.

Both films use interviews, voiceovers, and archival footage to explore the thinking behind each artist's work. Peña devotes a chapter to Steir's friendship with the musician John Cage and how his ideas about non-intervention and chance inspired Steir to adopt a new approach to her painting. Determined not to touch the canvas, she poured the paint onto it, allowing it to make the picture. "I took just the brushstroke, the icon of abstract painting, and let gravity play with it." Once Steir established the limitations (colors, canvas size, viscosity, the wind in the room), her job was done.

Throughout the film, Steir revels in the benefits of her uncontrolled process. Letting gravity do the work allowed her to remove herself from the picture and relinquish her ego and body. Free from responsibility, she never had to fight her work the way Abstract Expressionists did. If the paint didn't "do something pleasing," it wasn't her fault. If the work was beautiful, she took no credit.

For Steir, embracing mistakes, misjudgment, and miscalculation is also essential. It's not a fluke that the first of her famous waterfall paintings was an accident and is now hanging at the Metropolitan Museum of Art: "If you correct a mistake with another mistake, it makes a masterpiece. Two mistakes are great. One mistake corrected correctly -- then it's a wreck."

Steir allows her materials to guide the work. Von Rydingsvard bends them to her will. When she speaks about her sculpture, the focus is on the materials and the processes they entail. Best known for her work with cedar, von Rydingsvard was taken by the wood's soft, sensuous nature when a friend brought her some 4 x 4" beams. Because it didn't have a lot of grain, she could "use it and abuse" in ways that were "almost outrageous."

The artist traces her affinity for wood to her experience of living in a displaced person camp after the war: "Everything was made with wood: the floors, the walls, the ceilings, the doors, the staircase going up. And it was made in a very rough, rugged way. There was no insulation. So it was just the board between me and the outside world. And I recall my body being right next to the wall, and I could smell, I could feel. And there was a huge difference between what had happened within this wooden structure and what happened outside of it, so that there was a kind of safety the wood gave me."

The essence of von Rydingsvard's work is about touch, and Traub conveys this idea through close-ups of her hands. There's something intimate in the way her fingers burrow into the crevices of the wood as she carves.

Late in the film, as people outside the Barclay Center in Brooklyn explore "Ona," von Rydingsvard says in her earnest, whispery voice, "I do want people to touch the sculpture, and I do want their fingers to make a mark. There's acid on the tips of your fingers, you know, that can eventually eat away at the patina. And I like that look. It's like the look of the Buddha's belly that get rubbed historically. And that part shines from all the rubbing, and Ona is awaiting that."

The joy of these films is watching the artists at work and viewing art in close-up. We see the techniques Steir uses to change the paint's quality - thinning it with a spray bottle, wiping it with a tissue, dragging the bucket along the top of the canvas as the paint falls, then using her brush to give it a little downward push as the camera slowly pans down to capture gravity doing its magic.

Film is a great medium to showcase abstract art as it highlights paint's texture, translucence, and movement. Steir's canvases drip and glisten with life. The surface of "Lila Judith" is reminiscent of bark yet somehow more beautiful.

Steir keeps all her unfinished pieces out in her studio and walks around them, sometimes for days. She knows that to her assistant, it looks like she's doing nothing. "It sounds like such a hippy-dippy thing to say -- I wait til the painting tells me what color to put on." I like how Peña echoes this meditative process with soft-focus shots of her fingering flowers in a garden or absorbing the city as she moves tentatively through Greenwich Village with a cane.

Steir’s zen-like studio could not be more different than von Rydingsvard's collaborative, cacophonous workshop, which evokes a medieval atmosphere: melted bronze glowing in a white-hot cauldron, copper hissing and smoking when wiped with a cloth, the sizzling ends of an iron tool, relentless hammering, clanging, and pounding. You can feel the heat and sense the danger. Yet from the film's opening image of von Rydingsvard putting on worn gloves and stuffing sharpened black pencils into her back pocket, it's clear that she’s in her element.

Because the nature of von Rydingsvard's work is collaborative, we rarely see her alone or in silence. At fabrication shops and on-site, she works side by side with artisans and construction crews. I love that she and her assistants eat lunch communally at her studio.

Despite being in their late 70’s, Steir and von Rydingsvard are undaunted by the physical challenges their work presents. Nothing can stop them from making art. In my favorite moment in Peña's film, an assistant helps Steir step onto an electric lift. She then rises to the top of a canvas twice her size and matter of factly begins to paint.

For Steir, art is a religion she must continue to practice: "I want the paintings to express something in the will of nature … like when a physicist looks for what makes the universe hang together, I was looking in color and paint for what makes the universe hanging together … for the equation that says, ‘this is why all the planets don't fall down on our head. This is why we're sinking into the abyss ‘… That's what I'm looking for in my paintings. It sounds so grandiose to say, but it's this spiritual quest."

I'd never heard of Steir, and after seeing her work, I felt angry that she's not a Jeopardy answer like Pollock or DeKooning. But that was not her goal. "I wanted to be a great artist … not slang for someone who is great. But in the fantastic, reaching the soul of other people."

If Steir's drive to make art is a spiritual quest, von Rydingsvard's is to survive. Her friends and colleagues refer to her "deep, deep need" to be an artist. How does making art sustain her? In her new memoir, Sanctuary, Emily Rapp Black offers a possible explanation: "Focused effort and striving might lead to wholeness or happiness … All creatures are built to make efforts to survive … To fight for life is what makes us alive.”

Von Rydingsvard admits that she gravitates to labor-intensive work. Bronze, copper, resin — each new material presents another battle to prove her father wrong and gain sustenance. Watching her crew assemble the copper puzzle-like pieces of Uroda, she personifies and identifies with her emerging creation and remarks, "She's coming into her own. She needs that scale." Von Rydingsvard’s sculptures aren't bulwarks. They're symbols of her resilience.

In Traub's film, the artist Sarah Sze proclaims that if art hasn't saved your life in some essential way, if it doesn't have a kind of life force, then you probably won't continue making it. This is true for Steir and von Rydingsvard, but I don't believe it applies to everyone. Being an artist is not predicated on life and death. I could survive without writing. I just wouldn't feel nearly as alive.

I have the Steir doc on my watch list and I happened to decide to watch the Ursula piece yesterday! I love her work as I have experienced it in person and unrelated...( I completely forgot her use of graphite) I am using so much graphite on my current sculpture. I “get” both women in terms of “why” their art and Ursula is killer. That said, I look forward to the Steir doc! Loved your review. Thank you for your writing.