ARTWRITE #14: Making Art in 2020

Joel Adas, Margaret Zox Brown, Philippe Cheng, Theodosia Marchant

12/31/2020

For this end-of-year issue, I'm not going to list my ten favorite artists of 2020 or tell you which ArtWrite post got the most Instagram likes. No highs and lows, grand conclusions, or predictions.

I'm more interested in how this past year has impacted artists' creative process. How did the pandemic and BLM affect making art? What happens when artists can no longer work in their studio? Do they feel more compelled to create, or does making art feel indulgent when so many people are suffering?

In November, I reached out to several artists whose work I'd posted on Instagram. Four agreed to answer a set of open-ended questions, and I used the same questions to reflect on my writing:

How did your work and/or your approach to writing change in 2020?

The LA lockdown began as I was impatiently waiting to hear back from the agents I'd queried about my first novel. At the same time, I was struggling to gain traction with a new project. I longed to be in the mode I'd been in months before when I had peak momentum and no interest in doing anything other than writing.

I managed to map out some ideas for a novel, but it was slow going. In July, I began using ArtWrite to explore some of the characters. I also wrote two poems and some personal responses. That felt good. But once I started interviewing artists, the newsletter became more compelling. I worried that the newsletter was an excuse to avoid writing fiction and felt guilty because the process of choosing images and editing interviews was so much easier than confronting the blank page.

When I began to connect my personal experiences to the art in the newsletter, something clicked. I feel like I'm writing again and that my engagement with the artwork has deepened. My new approach to the newsletters seems to resonate well with readers, so I feel like I'm on the right track.

Where were you in 2020 and how did that affect your practice?

I've been in LA. Working from home is fine if I'm immersed in a project. But when I'm at an early stage and lack confidence and flow, I get distracted by cobwebs under the molding or the leftover Indian food in the fridge. That's why I've always preferred working in a library, hotel lobby, or at the Hatchery, a writers' workspace in LA. Even though I rarely speak to anyone, something about the ambient buzz of people helps me focus.

My younger son has autism, and in April, he moved into a transitional living program. Suddenly there was no reason why I had to get up in the morning. As my husband and older son typed and Zoomed away in their workspaces, I would rewatch Mad Men, nap, or doom scroll before dragging myself out of bed to write for an hour.

ArtWrite saved me. It gives me structure and purpose while also allowing me to feel connected to the outside world.

How did your perception of yourself as a writer change in 2020?

I went into 2020 wanting to sign with a lit agent and sell my novel. I needed that validation to feel like a writer. After querying over 60 agents and getting a dozen requests for my full manuscript, I didn't receive any offers. People who love me (and my book) blame the rejections on how BLM and the pandemic have changed the publishing industry. I don't. My novel needs work.

The weird part is, I feel more like a writer now than I did last year. More people are reading my writing than ever before. I've also finally figured out the truth: a writer is someone who writes.

Any other thoughts about writing in 2020?

Philippe Cheng, one of the artists interviewed in this issue, sent me a holiday card with this Rilke quote: "We see the brightness of a new page where everything yet can happen." As much as I dread the blank page, Rilke is right.

--Maggie Levine

ArtWrite Interview: JOEL ADAS, MARGARET ZOX BROWN, PHILIPPE CHENG & THEODOSIA MARCHANT

Philippe Cheng's 2015 book, Still, The East End Photographs, captures the serenity and changing light of Long Island's landscapes and seascapes. As 2020 comes to a close, Cheng is currently working on a portrait series to document this historic time and support local cultural arts institutions.

How did your work and/or your approach to making art change in 2020?

Philippe: The past year has informed and reminded me of the importance of the moment, artistically and politically. No time like the present, as the inspiration can come and go so quickly.

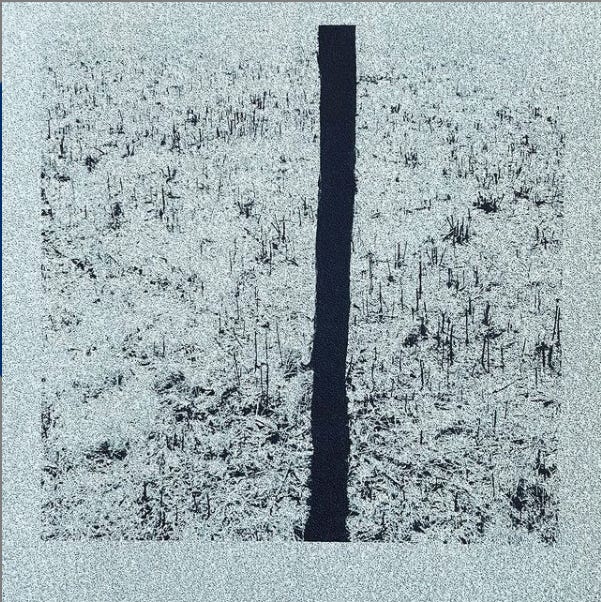

I've had more time to observe, to challenge myself, to look for alternative ways to use photography, and to advance other parts of my creative process. For instance, I have considered how to make photographs more tactile for years and have begun printing on sandpaper.

I've also been doing sculptural work for the first time. My site-specific installation, "Cadence,” explored an idea inherent in my photographic work, searching for light where it is often unacknowledged or unseen. By placing the sculptural form on the same level as the low ground cover, the metal's reflective quality animated light that would otherwise have gone unnoticed.

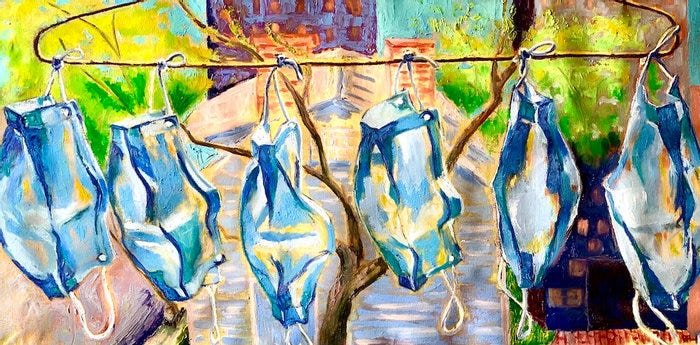

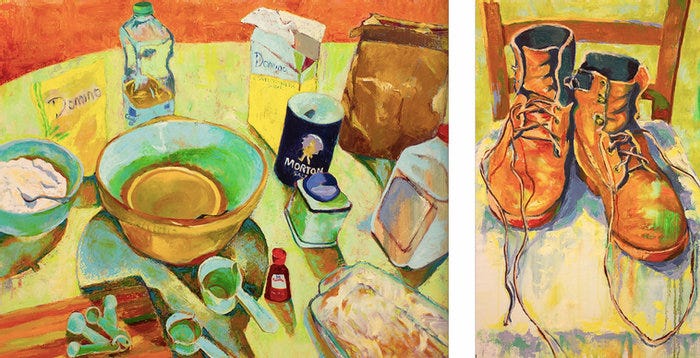

Even from a young age, Margaret Zox Brown felt drawn to human connection, and it's this impulse that makes her work so intimate and accessible. Her colorful oil paintings focus on the beauty of quotidian life, be it the people she meets on the streets of NYC or the seemingly mundane aspects of her life during lockdown.

Margaret: Drawing has always played a significant role in my painting. In the past, I would begin by drawing loose pen sketches. When I came across one that really popped out to me, felt strong on some level, I would paint that image. In 2020, my approach changed. I'm a more evolved painter and have a clearer vision of what I want to express and an urgency to share what I feel is important. As a result, drawing is no longer just a visual connection with the form; it has become an unearthing of the emotion I seek to convey. I then seek out the figure, scene, or even shapes and light to help me express them.

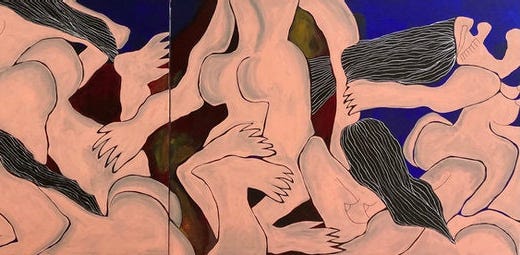

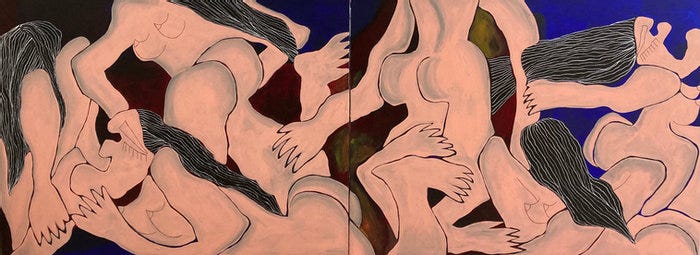

Born in Athens and now based in LA, expressive figurative artist Theodosia Marchant explores the nature of human existence in paintings as dramatic as Greek tragedies. Naked figures fill orgiastic canvases, overlapping and intertwining with each other, vines, and foliage, so it's never clear where bodies begin or end. Faces are either hidden by manes of hair or have a mask-like quality. Marchant's frequent use of horizontal composition reminds me of ancient drawings on walls and urns, as well as Picasso's "Guernica."

Theodosia: I had "big" plans - I had already started visualizing a new series with a slight departure from my usual figurative work. I had named it "Cyclone'' - fittingly, it turned out as we plunged deeper into the pandemic. The series has developed throughout the last few months.

My artistic language has taken a turn for the noir, a shift that reflects my feelings. At the beginning of the lockdown, truthfully, I had very little desire to do anything: no one was buying, and all gallery shows were either canceled or moved online. After a month or so, I pushed myself, and it's certainly helped give me a sense of normality again. We must keep moving no matter what life throws at us.

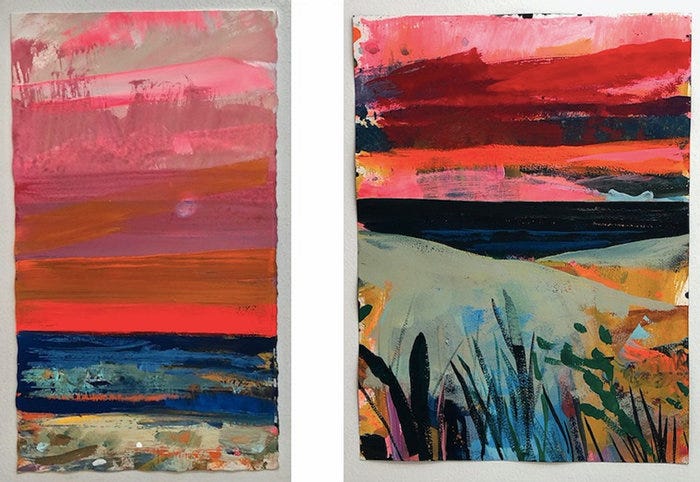

Joel Adas is an expressive landscape painter based in Brooklyn. Growing up in New Jersey, the ocean has always had a pull on his imagination and creative impulses. Relying heavily on improvisation, Adas produces paintings that feature gorgeous color combinations, layered surfaces, and vigorous brushwork.

Joel: I'd always considered myself a studio painter working primarily in oils and occasionally doing gouaches at home. When the pandemic set in, my wife and I relocated to Cape May, NJ. I no longer had a studio and quickly realized that the best approach to artmaking would be gouaches. They take up less space than canvases, are stackable, and the water-based paint eliminates fumes and makes cleanup easier.

In my Brooklyn studio, I had one long wall and would often have ten oil paintings going simultaneously. To replicate this practice in Cape May, I have found some flat areas where I can lay works and pick and choose which ones appeal to me. I try never to work on a painting unless something leads me into it.

Because of my direct connection to nature in NJ, I was soon painting the beach, a subject that has always fascinated me. To have it in my mind so clearly made it a natural focus. In "Mauve Dusk," I wanted to convey the fantastic array of colors at that time of day, the sense of walking onto the beach, and the calm and serenity that the beach at dusk provides.

Where were you in 2020 and how did that affect your practice?

Joel: In Brooklyn, there was always a subway ride or a long walk to the studio. I loved the commute because I'd get my head in the work by anticipating what I'd do in the studio. But now, I can paint for an hour or so, do a few errands, come back, and continue, like a good book that you can't put down. One evening, I left "Sea Through the Dunes" on the table. When I looked it over in the morning, I immediately saw that the sky was not quite right. I put a red swath across the top with a few strokes, and it fell into place. Having my work so close at hand has given me new-found freedom and allowed me to be much more prolific.

Philippe: I have been on Eastern Long Island, where I have lived and worked for the past nineteen years, in my studio and the environment. People define this area as the affluent "Hamptons," but the reality is far more complex and diverse than the public realizes. The work I've done in 2020 has focused on visually capturing what is here and what is unseen. For example, the land in Long Island is the ancestral land of the Shinnecocks Indians, and residents are reconsidering what this means, practically, emotionally, culturally, and politically. For an exhibition on the Shinnecock Reservation in Southampton, I made a sculpture using the location's coordinates as there was no official address. These are not just numbers.

Theodosia: I have a two and a half-year-old son. With the lockdown, his daycare had to close, so he's been with me full time ever since. Because my art studio was a shared area, I had to let it go. At home, I set up an area outside for the larger sized works and space inside for smaller ones. It worked. I was able to look after my son and enjoy interacting with him.

Margaret: I have always painted the beauty I find in the quotidian. Since Covid and setting up a temporary studio in the apartment above ours, the intention of my art has become even more apparent. Because I had a studio right upstairs where my dog could easily join me, and I could wear my slippers to get there, "home" became a natural focus for my work. Since Covid, I have been painting the beautiful moments that I (and thus, by extension, we) can find at home.

How did your perception of yourself as an artist change in 2020?

Joel: With sheltering in place, the home has become more significant. Art is something that people can turn to, to ease their mind amidst all of the worry. It's a visual sanctuary.

I've always wanted to make a living selling my work, and for the first time, that idea does not seem out of reach. Because I'm no longer traveling to work in museums or teaching in schools, I have more time to paint, document the work, and update my website. Before 2020, I never went directly from creating a painting to posting it on Facebook and Instagram the way I do now.

I'd always thought that a gallery would eventually represent me. I now realize that I can successfully sell my work with no middle person. That discovery has been incredibly liberating.

Margaret: Everyone is behind their computer, traveling the world virtually; everyone's homes have become their world. Art has always been a statement of culture, as well as an embellishment to life, but now its significance seems to be even greater. By recognizing that, I have become more confident about my role as an artist. We need art to connect us now more than ever, so I am meaningfully contributing to society. In my series, "The Lockdown Paintings," instead of reacting to the world with an agenda, I respond with the authentic feelings that this unique time has brought up for me. Wearing masks or exercising at home while your pet's in the way reveal life today, without adornment. They are a record of the time.

Theodosia: I certainly feel a greater desire and pressure to realize work that reflects what we’re going through and to document this time in my figurative style. We all need an outlet and reassurance that even though life as we knew it might have changed, the framework we hang our lives around is still there and can be rearranged. We need to keep the flame alive, not only for our survival and well-being but for everyone out there who is interested in the arts and needs an escape too.

Philippe: The issues of social justice and the urgency of the political moment have made me think about how I can use my skillset to make a difference. Even though our culture is overwhelmed with images, there is still a role for photographers to use their educated eye to make curated images that reflect the historical time we're living in. This idea is evident in my documentation of social justice marches on the eastern end of Long Island and in "Pause Portraits," a series of commissioned portraits of families, essential workers, and visually underrepresented artists of color.

The past year has reaffirmed my commitment to making images that convey ideas that matter to me as an individual. Art is a part of my everyday life. I don't disassociate it from the world around me. I strive to be mindful and responsive to social justice issues while still making beautiful and meaningful work.

Any other thoughts about making art in 2020?

Joel: My experiences in 2020 have made me realize how critical visual art can be in people's lives. In my correspondences with people who have bought my work, their passion for looking at art is palpable. This urgency is a far cry from the old saying that art's only purpose is to look good over a couch.

Theodosia: It has kept me sane. The first couple of months under lockdown were the most harrowing; asking questions and not finding the answers was new and disconcerting. The feeling of the turmoil unremittingly expanding was pretty desperate. Inevitably and quintessentially human, I eventually accepted that it is what it is and began to adjust and carry on. I try not to dwell much on the negative side of the present conditions and just carry on with my work.

Margaret: Unbeknownst to any of us, 2020 has become a true turning point in how we live and experience all of life. Because of the way we're all living now, we've been forced to see our home surroundings differently and appreciate things that might have been in the background before. I now see a kitchen counter filled with baking supplies or a pair of worn boots for the beauty of their shapes and their meaning. 2020 has shaped so many of us, and making art in 2020 is a record of that transformation. I am excited by it all.

Philippe: To make. To see. To appreciate. Even more than one thought possible.