ARTWRITE #13: Pattern Part 4

Elizabeth Alexander, Cynthia Carlson, Mary Grigoriadis, Valerie Jaudon, Joyce Kozloff, Miriam Schapiro

12/19/20

My mother wasn't an artist, but she was creative. In our living room, some of her artwork hung on the walls: a relief-like sculpture, a pair of Picasso-esque cubist still lifes, a collage of enameled pieces mounted on cork, an abstract mosaic. No one ever discussed them. No one asked where they went when other artwork replaced them. The only thing I knew about them was that my mom had made them during a vague post-collegiate chapter of her life that included getting married.

My parents never celebrated their anniversary. Whenever I asked when it was, my mother dismissed the question with an irritated eye roll, similar to the one she gave me when I asked why we didn't celebrate any Jewish holidays if we were Jewish.

There were a lot of things about my parents that didn't make sense. That's how I justified my constant snooping. When I was a teenager, I found their marriage license in a strongbox on the highest shelf of what my parents casually referred to as "the secret closet." April 18, 1957. I imagined surprising them with a cake until I thought about the year. My sister had been born in November of 1956. Old enough to connect the dots, I figured my parents had kept the date a secret because they didn't want their daughters to have a cavalier attitude about pre-marital sex.

Years later, I learned that they'd hid their anniversary to protect my mother from reliving the trauma surrounding her pregnancy. She was only 20 and must have been terrified. My grandmother responded to the news with shame and fury. My mother temporarily left home, and it was a long time before my father was welcome. Because of my grandmother's reaction, my mother shrouded her pregnancy and marriage in shame and secrecy. As if it could make the pain go away, she shoved this chapter of her life into a box and hid it in a closet. I assumed the part of her that made the art in the living room also disappeared into the secret closet.

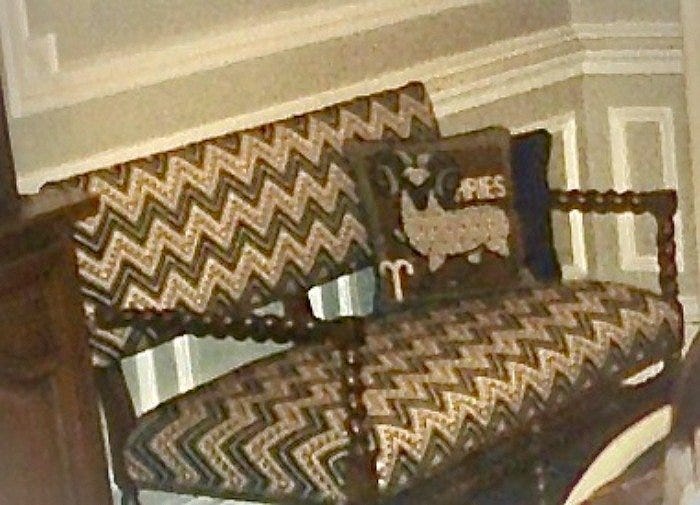

Six years after my sister, I came along. By that time, my mom was constructing crepe paper butterfly wings for my school play, beading Christmas ornaments, sewing and embellishing skating dresses for my sister, decorating and redecorating our home, taking cloisonne jewelry classes, and needlepointing.

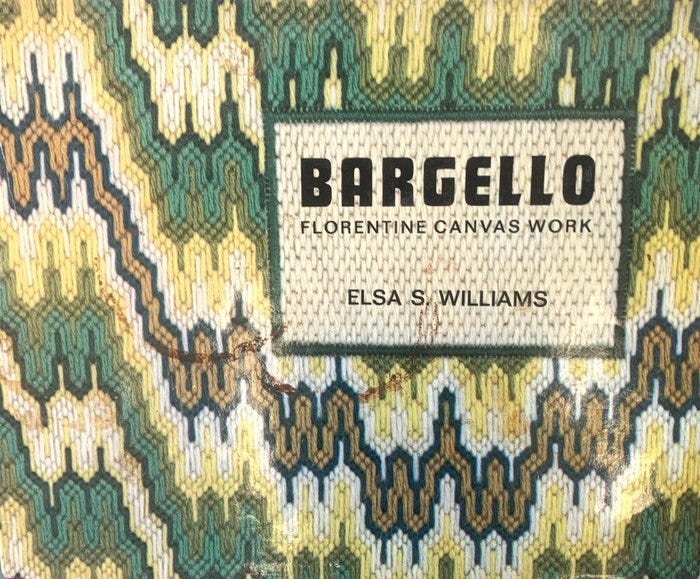

Not just pillows like the one in the photo above. My mother spent two summers with huge canvases draped over her lap. The result was a love seat covered in one of my favorite patterns, Bargello.

In the last chapter of her life, my mother returned to fine art classes. She was a widow living in Florida and looking for ways other than golf and tennis to flesh out her life. She trained to be a volunteer guardian ad litem, but that didn't last. She took some classes -- sculpture, watercolor -- but nothing stuck. She was never happy with the results. I was disappointed that she didn't push herself and accused her of being perfectionistic. With decorating or needlepoint, she could control the outcome. But with art, there was no pattern to follow.

My mom died in 2014. I didn't put much thought into the arc of her creative life until this year. The shift began right before the pandemic when I went to MOCA in LA to see "With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972-1985." The show featured many of the craft-based practices my mother had worked in, including needlework, beadwork, mosaic, and ceramics. She would have loved it.

I'd never known there was an actual movement called Pattern and Decoration, and I don't think my mother was aware of it. P&D artists "used abstract design as a primary form and ornament, as an end in itself. They took beauty, whatever that meant, as a given." Spanning from the mid-1970s to the early 1980s, P&D was born in response to the domination of Western, white, male aesthetics at a time when the art world revered the sleekness and purity of minimalism. The movement challenged the notion that fine arts ranked higher than decorative or handmade arts while also defying modernism's rigid inclusivity. Aesthetically and politically inclusive, P&D celebrated realms traditionally perceived as feminine, domestic, ornamental, craft-based, or decorative. It also valued overlooked artistic traditions from other continents, such as Islamic motifs, Persian carpets, and Japanese ceramics. P&D artists erased the distinctions between art and design, high and low, object and idea.

In addition to featuring pioneering P&D artists, the exhibition also included artists whose contributions have been underrecognized or not generally connected to the movement. (For a fascinating explanation of the show's curation, watch Sandford Biggers's "Artists on Artists" talk).

To give you a sense of the show, I've selected a few seminal pieces, followed by one of my favorites. Except for Miriam Schapiro who died in 2015, all the artists I've included continue to make extraordinary work.

Miriam Schapiro celebrated women's artisanal work while merging it with the feminist thinking of the day. Her pieces included elements and imagery associated with femininity (hearts, floral decorations, geometric patterns, fans, the color pink) and conventions found in quilting, embroidery, and appliqué.

Mary Grigoriadis saw her work as "a paean to beauty, opulence and order." By referencing the ornate patterns of Byzantine mosaics and icons, the artist affirmed the role of pattern in art history, architecture, and in global women’s crafts. Her richly hued, oil on linen paintings were "decorative without apology”

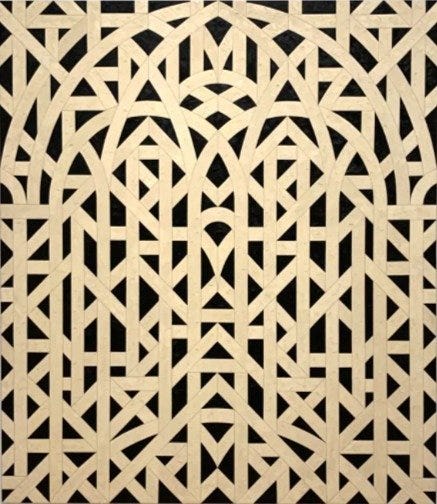

Valerie Jaudon's paintings focus on the sheer beauty of ornamentation. Her isolated abstract, geometric patterns allude to global traditions, but because she presents them without context, her subjects become objects of "esthetic contemplation."

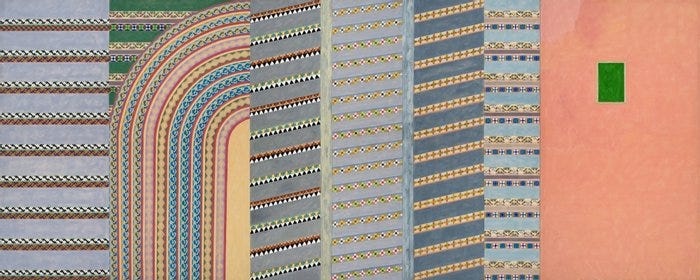

Throughout her career, Joyce Kozloff has tried "to fuse a love for widespread artistic traditions with an activist temperament." Her early Mexican and Islamic-inspired works featured motifs rooted in ornamental architectural patterns. These pattern-based paintings evolved into installations that included hand-painted, glazed ceramic tiles, and pieced silk wall hangings.

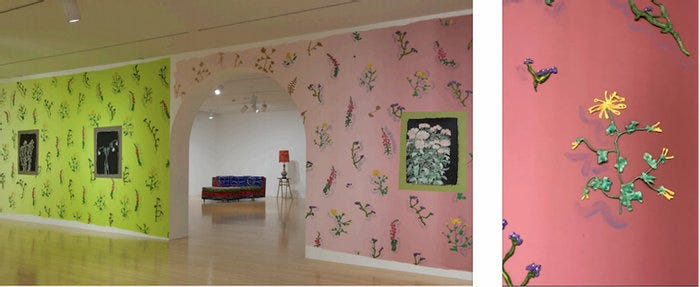

The piece below was one of my favorites. In the 1980s, Cynthia Carlson created playful site-specific installations of “sculptural wallpaper" all over the US. For the MOCA show, the artist adapted the installation she'd created for MIT in 1981.

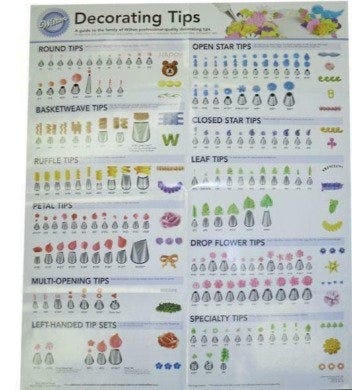

Take a look at those glossy flowers on the wall. Carlson piped them with a pastry tube.

Talk about honoring women’s work. I'm an avid baker with a drawer full of Wilton decorating tips that never get used because I'm lousy at piping. (I baked my wedding cake, but rosettes, scrolls, garlands, latticework, basketweave were all non-options; the best I could do was sugared rose petals). I just loved how Carlson’s room gave cake decoration its due while at the same time giving the patriarchal art world the finger.

(BTW: if you don’t believe cake decorating constitutes art, take a look at these cakes from Amanda Faber who paints with frosting).

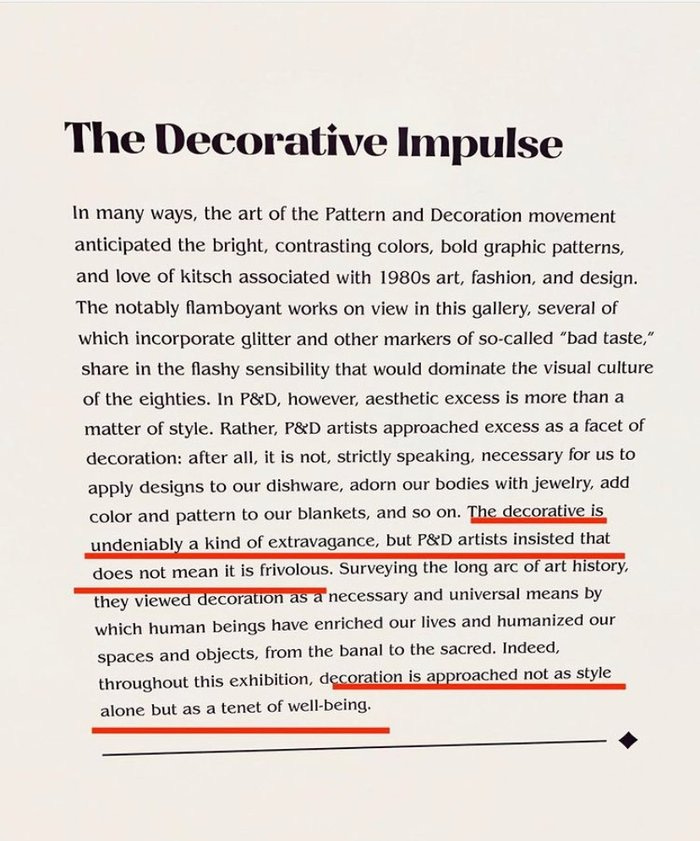

Before leaving MOCA, I read the wall text below. Little did I know that I was about to have an epiphany.

Yes, I loved the exhibition, but I felt guilty for loving it. Deep down, a part of me had always bought what the art-world bigshots were selling: That wallpaper was superficial. That I should push my brain to appreciate intellectually rigorous art. Not to mention my extant adolescent need to rebel against anything associated with my mother.

The wall text spoke to me. The decorative was not frivolous. It was okay to love things just because they were beautiful. I snapped a picture, determined to hold on to this wisdom. When I posted it on Instagram, my college friend Doug commented: "Love what you love, decorate away. It's only a blip on the radar of human history that something beautiful is discouraged." Guilt had no place in art. The fact that Doug is also an interior designer doesn't make him any less right.

I continued to think about the problematic high art/low art hierarchies inherent in art, as well as the idea of impulse. Shouldn't the urge to create be considered as much an attribute of art as context, concept, or even execution? My friend Sarah, a hardcore knitter, reminded me that the Scots didn't have to invent dyes to vary the colors of their Shetland sweaters, yet they did. Same with the intricate patterns on Norwegian sweaters or Native American blankets. The inclination to beautify objects or our surroundings is innately human, and so is my ability to appreciate it. It's a gift, and I was through questioning it.

Because my mother gave me this gift, I also began to reconsider her creativity: I'd told myself a story about her buried artistic dreams, never considering that she might have been content to sew, decorate, needlepoint, and do the calligraphy on my wedding invitations; As much as I loved the bargello couch, I’d always hoped she'd stop doing needlepoint and become a real artist. That's why I was so disappointed when she quit her watercolor and sculpture classes. I couldn’t fully accept how she channeled her creativity.

People twist themselves in knots because the word "artist" is so loaded. A lover of craft projects, the writer David Rakoff admitted that his insistence upon producing useful items was spurious: "If I stress utility, I will be less tempted to think of the visual stuff I make as 'art,' and consequently of myself as a you-know-what, a label really only rightly conferred by others." Thanks to what I've learned from the P&D movement, I can now confer the label on my mother. She wasn't just creative. She was an artist.

Wallpaper Finale

Since this series began with wallpaper, it seems fitting to end with it. However, instead of sharing work inspired by wallpaper, I'm excited to present something better, art made from wallpaper.

Elizabeth Alexander creates individual, pieces, installations, and photos using wallpaper and other found materials. Her practice explores abstract ideas that permeate physical homes: status, security, human presence, privacy, and the fragility of stories and memories. I would kill to see Alexander's work in person.