ARTWRITE #10: Pattern Part 1

Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Bruno Leydet, Nikki Maloof, Aliza Nisenbaum, Uzo Njoku, Patrick Quarm

11/28/20

I was ten the first time I committed to wallpaper, a pattern of tiny rosettes for the living room of my dollhouse.

My mother was a serial redecorator. Fabric swatches were always lying around the house, and if I needed to take a phone message, I usually ended up writing it on the back of a floor plan sketched on a paper napkin. When my mom was considering wallpaper for a room, she'd tape samples to the wall. It was the 1970's, so bold, graphic designs in metallic silver and matte neutrals were big. As I ate breakfast or brushed my teeth, I'd stare at the shiny patterns, trying to figure out how they managed to be so different and similar at the same time.

Three decades later, I considered wallpapering the bedroom I shared with my husband. But the commitment scared me. What if we got sick of it? I ended up doing just the wall behind our bed.

To find wallpaper for the bedroom, I headed to the Upper East Side, determined to infiltrate Manhattan's infamous fortress of decoration and design, aka the D&D Building. Ignoring the brass "for the trade only" plaque mounted outside the entrance, I tried to look like I belonged there.

My usual desire to check my phone disappeared as I explored the D&D's 17 floors of showrooms. Racks of glorious patterns lined every wall of Cowtan & Tout, Donghia, Schumacher, and Osborne & Little. There were stripes of every width: pencil, chalk, candy, awning. Herringbones, chevrons, argyles, and houndstooth. Tartan plaids. Madras plaids. Florals, botanicals, jungle, and animal prints captured the natural world; toiles, jacquards, paisleys, and ikats evoked foreign countries. I was in pattern heaven.

Why was the D&D experience so exhilarating? What makes patterns so compelling? Feeling connected to my mother and how she valued aesthetics was a part of it. She had died the year before, and I liked being in her world. There's also the hypnotic, infinite nature of repetition; until patterns are on a wall or upholstered to a chair, they're indifferent to borders or frames. Or, maybe it's just because they're beautiful.

I now have a new way to indulge my pattern obsession: finding artists who use it in their work. The internet gives me limitless options. I’ve spent the past few months learning about artists and reaching out to them to get permission to post their work. When I decided to feature them in the newsletter, it took me a while to figure out how to organize their varied approaches. In the end, I came up with a split between representational and abstract work. This issue focuses on the former.

Aliza Nisenbaum is one of my favorites of the representational painters. I love how fearlessly she juxtaposes multiple patterns. When she was growing up in Mexico, Nisenbaum's family collected textiles. She describes their home as "the opposite of minimalist – it was maximalist." Nisenbaum paints realist portraits of people from diverse and underrepresented communities. She develops strong personal connections to her subjects, and her unabashed use of pattern and color is "a way of enveloping, even embracing [these] subjects in richness."

In his homoerotic portraiture, Montreal-based painter Bruno Leydet's approach is playful and allows for a little more breathing room than Nisenbaum's. There's something amusing about how he patterns every element on the canvas, right down to the teacup and saucer.

Nikki Maloof's rug, tile, and upholstery patterns enliven rooms that crackle with tension upon closer look. With its floral wallpaper and needlepoint pillow, her guest room is charming. Except something is off. The black and white spiderweb design feels like it belongs in the room of someone from the Addams Family. Also, because the bedspread pattern is even more ornate than the wallpaper, and their scale is roughly the same, the effect is dizzying. On top of that, there's a dog hiding under a bed that looks like it's about to slide off the frame. The whole room has a disquieting feeling that reminds me of Charlotte Perkins Gilman's "The Yellow Paper." Staying there might drive you mad.

What I love most about Nisenbaum, Leydet, and Maloof is that like fashion and interior designers, they understand how to combine patterns that clash, but in a good way. It's not easy to pull off.

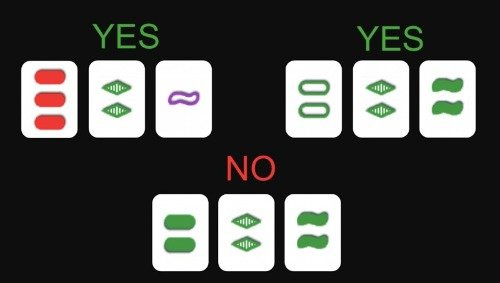

I asked interior designer Sasha Emerson what her secret is to mixing patterns. She said it's about ignoring the limits of color, scale, form, or image. Dissonance is key; the more unrelated two patterns are from each other, the better. (My husband said this is the opposite of the game SET, where the object is to find sets of related patterns).

Several artists with African roots use native patterns in work that often expresses their blurred identities. Uzo Njoku was born in Nigeria and immigrated to the United States when she was seven. The youngest artist featured in this issue, Njoku did not begin painting until she was in college. Njoku's portraits explore the "psychic landscape of black femininity." Her coloring book of inspirational women, each set against an intricately patterned backdrop, has sold thousands of copies.

The first time I first saw Njoku's work on Instagram, I immediately thought of Kehinde Wiley. While Njoku uses bold Ankara prints to celebrate women, Wiley employs decorative motifs from different cultures to reimagine his subjects in the style of traditional European portraiture.

I will never forget walking into Wiley's exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum (this was before he painted Obama's portrait). My jaw pretty much dropped when I saw the walls exploding with sumptuous patterns. My family had to drag me out of the show, but not before I'd photographed every single background.

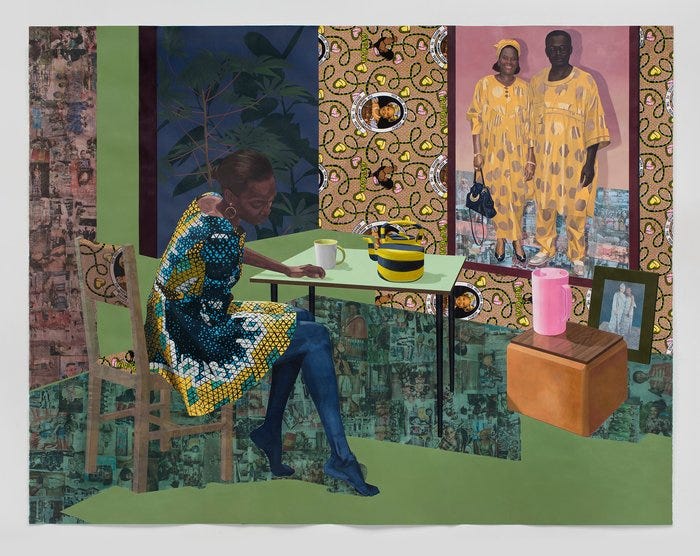

I recently read that Njoku cites Wiley as one of her two major influences. The other is Njideka Akunyili Crosby who was also born in Nigeria. Crosby uses a photo transfer process to creates patterns made of personal photos and pages from Nigerian magazines. Her layered "collage paintings" address the challenges of occupying two worlds and living in culturally ambiguous spaces.

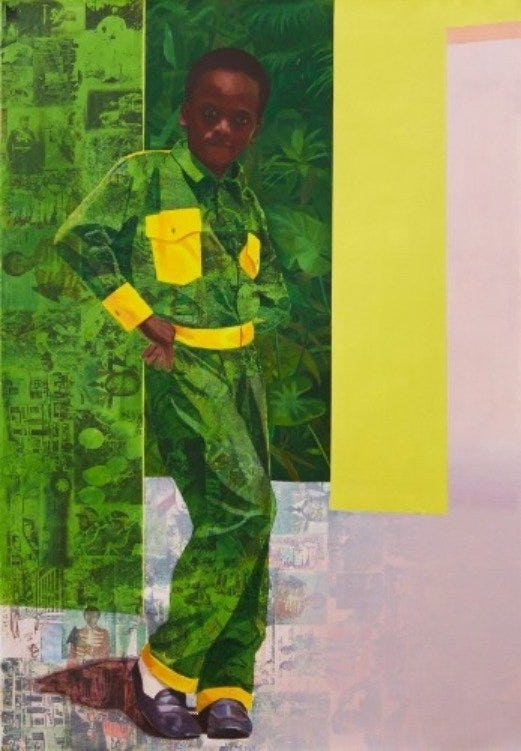

Ghanaian artist Patrick Quarm also explores what he calls "cultural hybridity." He combines traditional African prints with florals and graphics, sometimes superimposing pattern directly on his subjects to create a gorgeous tattoo-like effect. I love how the design on the boy's body in "Ledger of Truth" suggests how reading transports him to a different world.

Sadly, I wasn't able to contact Bisa Butler to get permission to show examples of her incredible work. She uses African textiles to quilt together life-sized portraits of African Americans from nameless photos.

Pattern is a tool for representational painters. My friend and artist Maureen Meyer described it as a "genius way of contextualizing" because the motifs, color palettes, etc. give subtle clues about the place, time, and circumstances of the work. Artists also use pattern to shape how they want viewers to perceive their subject. It can convey irony, reverence, power, a sense of home. It can amuse, disturb, or inspire.

The next issue will showcase abstract artists who take a different approach to pattern. For some of them, pattern itself can be the focus of the work. The issue will also include an interview with Mills Brown, Natalie Lanese, Daisy Patton, and Dee Shapiro.

For those who follow ArtWrite on Instagram and use the art to inspire your writing, I'd love to know where the work of these artists has taken you. In my writing, I sometimes focused on the pattern element, but not always. And that's fine. As long as the art gets you doing, it doesn't matter where it takes you.

To read the next issue about pattern: